Kenya still vulnerable to attacks despite changes

Garissa University College staff Isaack Kali shows where one of the students hid during last year's terror attack. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Unfortunately, since Garissa, the police have, more often than not, made matters worse, helping Al-Shabaab “terror-marketing” and undermining rather than strengthening public resilience. Possible threats are portentously reported in a cry-wolf manner, increasing rather than managing panic.

- Threats are never ranked, so the public cannot tell whether an attack is remote or imminent or whether the police are relying on deciphered electronic chatter or specific information from an intelligence asset.

On April 2, 2015 at 5.30am, five members of the Somali terrorist group, Al-Shabaab, stormed Garissa University College and took 800 students hostage.

Fifteen hours later, after a faith-based triage in which Muslims were freed and Christians marked for death, more than 140 students were dead.

The Garissa terrorist strike was the fifth and deadliest of the major terror attacks that took place in Kenya in the two years between 2013 and 2015: the 2013 Westgate attack, the 2014 ones in Mpeketoni and the two 2014 Mandera raids. In the year since Garissa, no terrorism event has taken place. The government says the Kenya is now safer; the police more agile and better equipped and the National Intelligence Service sharper in gathering intelligence and forestalling attacks.

The truth, unfortunately, is much more subtle: More has certainly been done but it is hardly enough. The population is no better prepared to cope with future attacks than it was before Garissa.

The police may be better equipped but decrepit hardware was hardly the reason for their inept response to previous attacks. Above all, the government mistakenly sees a re-think of the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) mission in Somalia – the real source of Kenya’s vulnerability to Al-Shabaab’s attacks – as a sign of weakness rather than strength.

The government’s big idea in the fight against terror has been to build force capability, strengthen information gathering and improve intelligence analysis. Though these measures are necessary, they are not sufficient. It is as important, to strengthen the public’s ability to face danger rationally, that is, in other words, to build public resilience.

A day before Garissa happened, there were fears of an Al-Shabaab attacks at other universities. Ten days after Garissa, a student died in a panic run at University of Nairobi’s Kikuyu campus after a faulty transformer short-circuited and blew up.

In December 2015, a bungled terror drill at Strathmore University fueled a social media frenzy of fear, panicked students into terrified flight and left one person dead and many more injured. Recently, rumours of an attack nearly led to tragedy at Kenyatta University, again.

These panics and stampedes mean that terror is working: It is exactly what Al-Shabaab wants. Al-Shabaab’s real weapon is its ability to inspire fear and panic that are disproportionate to its investments.

Unfortunately, since Garissa, the police have, more often than not, made matters worse, helping Al-Shabaab “terror-marketing” and undermining rather than strengthening public resilience. Possible threats are portentously reported in a cry-wolf manner, increasing rather than managing panic.

Threats are never ranked, so the public cannot tell whether an attack is remote or imminent or whether the police are relying on deciphered electronic chatter or specific information from an intelligence asset. The result is that the public assumes the worst and adopts exceptional measures, which merely magnifies the power of Al-Shabaab.

The starting point for building resilience and confidence is for the government to communicate better. In the State of the Nation Address, President Uhuru Kenyatta chided the press on how it communicates terrorism stories.

But sometimes the media lacks enough information from the government on the terror incidents. What exactly happened in Westgate when the KDF moved in? How can a garrison town like Garissa - the forward base for our border security - lack the capability to confront five terrorists? How many Kenyan soldiers died in El-Adde?

The mentality deeply embedded in the police psyche is that the more scared the public is, the more important their job is and so the more resources they can leverage from government.

The truth is that the hazards of terror might be with us for years. The police must be able to spot dangers and communicate them in a way that makes it possible for the public to respond realistically to possible threats and imminent dangers.

Building resilience involves normalisation: terror attacks, like natural disasters, might still happen even with the best security. The priority is to invest in the ability to respond and to protect critical infrastructure, both of which would minimise the impact of an attack and ensure that life goes back to normal with minimum disruption thereafter.

This means that people and institutions must be trained to respond to an attack. Investments must be made to set up adequate blood banks; secure communication networks - roads and telephones especially; build better rescue services and design safer shopping malls and public buildings to maximise rapid exit and reduce shrapnel deaths and injuries. Thus resilience: But it is not enough.

Kenya’s anti-terror strategy has focused on increasing force numbers and buying better equipment. But how would the 30 newly acquired state-of-the-art armoured vehicles have helped save more lives in Westgate Mall, in the Mandera bus killings or even in Garissa University College? Kenyan security forces should modernise but they should do this as a means of improving overall capabilities not essentially about fighting the terror threats that Kenya actually faces. Except for the Mpeketoni attack in Lamu and the El-Adde raid inside Somalia, Kenya does not face “battle-field” terrorism that warrants high-end armoured carriers. Al-Shabaab investment in its terror in Kenya has been very low-cost and principally in close-contact confined environments in which an armoured vehicle is useless.

Finally, Kenya has done little to address its source of vulnerability: KDF’s mission in Somalia. Al-Shabaab is an insurgency with a political agenda in Somalia. It has many goals, one is to get Kenya out of Somalia and another is to foment divisions between faiths in Kenya and, so to provoke the Kenyan government crackdown on Muslims. That strengthens its ability to recruit. The government says it won’t pull out in the face of attacks and many Kenyans agree.

The attempt to sour inter-faith relations between Christians and Muslims has only partially worked: the two faiths are not fighting but Al-Shabaab has provoked the government into a poorly informed crack-down on Muslims in the North-Eastern region and at the Coast, which in turn has helped Al-Shabaab recruit.

The truth is that the government needs communal support from Muslim groups to de-radicalise Al-Shabaab targets. Terrorism is not about religion. The role of religion in terror is ideological: It is merely what the terrorists use, first, to recruit foot-soldiers and, secondly, to build group solidarity. Their aim is to shift our attention away from their political goals to religious arguments. It is an easy trap to fall into.

Through this twisted ideology, Al-Shabaab has been able to takes its agenda forward. We have seen university students signing up for Al-Shabaab. This is the nature of terrorism and the way in which religion enhances its power to attract the idealistic. Groups like Al-Shabaab market the vision of a better world to idealistic youths living jaded lives.

They offer a world of high ideals without competitive materialism; of self-less sacrifice to a loving God and of egalitarianism and fraternity. It is an ideal immensely attractive to vulnerable youth living in corrupt, unequal and godless societies. Cracking down on mosques and radical youths merely helps Al-Shabaab propagate its message.

As to the Somalia mission, Kenya’s policy is now clearly driven by ego, not national interest. KDF’s original mission was to destroy Al-Shabaab and reduce attacks on Kenya. It should still be. Yet it is now clear that neither of these two goals have been met.

Al-Shabaab has responded to a stronger presence by African Union forces by ceding territory and melting into the population. It now operates guerilla-like, selecting vulnerable targets to maximise fear in and out of Somalia.

Once a group gives up territory, a conventional army becomes a blunt tool for fighting it: It becomes a job for specialised police units, such as the General Service Unit (GSU). That means that military defeat of Al-Shabaab is no longer a viable military objective. And since we won’t send in the GSU, the only real option is to build a legitimate Somali state that can effectively do the policing job.

There are claims the government in Mogadishu has said it wants KDF out. Partly because there is discontent in Mogadishu and a host of local clans. In the meantime, stories of KDF’s profiteering from its territorial control in Jubaland continue to leak, even as they are vociferously denied back home.

This is neither a recipe for stability in Somalia nor a strategy for weakening Al-Shabaab.

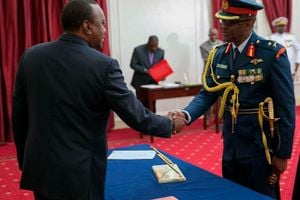

The danger stems from a pro-military bias and group-think in precisely those places where a re-think of Kenya’s Somali mission should happen. Except the police, all the critical security organs are headed by generals: Major-General Philip Kameru at National intelligence Service, General Samson Mwathethe at the Kenya Defence Forces and Major General (Rtd) Joseph Nkaissery at the Interior Ministry.

Given this, the prospects for a new strategy in Somalia are not good, suggesting that KDF will be mired in the Somali bog for the long-term.

This will only increase rather than reduce Kenya’s vulnerability to future terror attacks.

Mr Maina is a constitutional lawyer [email protected]