Hundreds of children under four live in prison with their mothers

Photo/PHOEBE OKALL

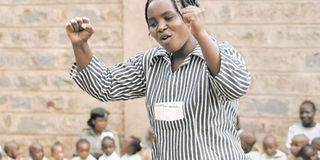

Lang’ata Women’s Prison theatre group member recites a poem “Strength of a Woman” during a ground breaking ceremony for an early childhood development centre at Lang’ata Women’s Prison last week.

Hundreds of children aged below four years live with their mothers in Kenya’s prisons, which are generally faced with, congestion, unhygienic conditions among many other problems.

Of the 361 children, 80 are with their mothers at the Lang’ata Women’s Prison. These children found their way into these prisons simply because their mothers were imprisoned, and that it was not advisable to separate them from their mothers.

This is despite the fact that prisons are not safe places for pregnant women, babies and young children.

When a mother is imprisoned, her young children may go into prison with her or be separated from her and left at home. (READ: My son thinks this cell is our home)

Both situations can put the child at risk. Experts say that children of incarcerated parents are six times more likely than other youth to land in prison at some point in their own lives, and the situation may be worse for the children living with their incarcerated mothers in prison.

Almost all the children are confined in the cells with their mothers throughout the day and night. An inmate who is a single mother told the Nation that when she was convicted, there was no one to remain with her two-year-old son and he had to accompany her to the prison.

Apart from the hostile environment, there is also the problem of the prison warders. Some of the prison warders are not role models, and the way they treat the prisoners may also negatively affect the children.

The law requires that in the control of prisoners, prison officers should seek to influence them, through their own example and leadership, and the officers are encouraged to maintain discipline and order with fairness but firmness. This is rarely the case.

Home Affairs PS Prof Ludeki Chweya says that it is sad that since they could not separate babies and young children from their mothers, they had to be in prison.

He however said that notwithstanding the complexity of the situation, there was totally no excuse for failing to protect the rights of children who have a parent in prison.

The prisons have guidelines stipulating the maximum age at which a child can remain in prison, which varies from a few months to four years. The impact this will have on the child’s life, as well as the conditions in which the children will be held, are to be considered when deciding whether it is in the child’s best interests to remain in prison.

No children in prison

However, these guidelines are not always adhered to, either because they allow for some flexibility in exceptional circumstances, or because the children cannot be cared for outside.

In India for example, children as old as 15 years have reportedly remained in prison with their parents, because nobody is willing to collect them. Other countries like Norway however, do not allow children of any age to live in prison.

An Educational psychologist Dr Josephine Arasa of the USIU said that the cognitive, emotional, physical, social and educational growth that children go through from birth and into early adulthood are greatly hindered if they are confined.

The environmental interaction influences behaviour, and that development is considered a reaction to rewards, punishments, stimuli and reinforcement.

Dr Arasa however warned that though early relationships with care givers play a major role in child development and continue to influence social relationships throughout life, the children risked being securely attached to those care givers. “Once they are removed from such prisons, they may have difficulty coping with the outside world,” she said.

In Kenya, the Faraja Trust, in collaboration with Kenya Prisons Service, has started a programme for the children imprisoned with their parents to mitigate the problem of becoming socially isolated by allowing them to mix with children from the surrounding area.

Last Thursday, Faraja Trust handed over to Lang’ata Women’s Prison an early childhood development centre to cater for these children. The resource centre, estimated to have cost Sh3 million, is meant to fill the gap that has been identified on the special needs of the offenders, especially those with children.

The children will not spend time with their mothers during the day, but will instead be taught at the centre and join their parents in the evening.

Ms Jane Kuria, the Trust’s coordinator, warned that the negative impacts of parental incarceration on children’s lives was unimaginable, and called for strong intervention that could help children realise their promise.

Faraja Trust’s founder Fr Peter Meienberg revealed that though it had been argued that having young children in prison with mothers can enhance bonding and avoid some of the negative impacts of separation for both mothers and children, this has not always been the case.

The reality is that the children have to live in the same conditions as their imprisoned parents, which are often unsuitable.

“There are no adequate resources to allocate additional food for children, meaning that parents have to share their meals with their children,” he said.

For the children to grow psychologically and emotionally, their lives should be as similar as possible to how it would be outside, and they should not be subject to the restrictions on their freedom that other residents of the prison are.

However, in the Kenyan prisons, the children cannot access education and do not interact with others, and this can affect their chances of successfully re-integrating into society at the end of a sentence.

Facilities in some countries, like the Aranjuez Prison in Spain, allow couples who are both imprisoned to stay in the same prison unit with their children under the age of three — to live in specially-furnished family cells, and have access to a prison playground.

The parents are also taught parenting skills and allowed to interact with their children in a more hospitable and less threatening environment than standard prison cells.

Home Affairs assistant minister Beatrice Kones acknowledged the fact that children whose parents had been incarcerated faced unique difficulties, and many were vulnerable to feelings of fear, anxiety, anger, sadness, depression and guilt.

She announced that the government would build structures in prisons to cater for the psychological, educational, social and emotional needs of the children whose parents have been imprisoned. Ms Kones warned that the impact of maternal imprisonment had to be seriously looked into.

“The behavioural consequences of such confinement can be emotional withdrawal, failure in school, and delinquency,” she said. The children are also vulnerable to feelings of fear, anxiety, anger, sadness, depression and guilt.

Deputy Prisons officer Ben Njoga said most women in prison were mothers of dependent children, and that there was adverse impact of imprisonment of mothers on their children.

“The imprisonment of a woman who is a mother can lead to the violation not only of her rights but also the rights of her children,” he said.