Breaking News: At least 10 feared to have drowned in Makueni river

Trial of Chad ex-leader Hissene Habre to begin next week

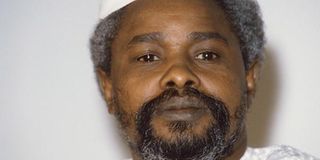

A file picture taken on January 17, 1987 shows Chad's then president Hissene Habre. Mr Habre's trial for crimes against humanity begins in Senegal on July 20, 2015. AFP FILE PHOTO | DOMINIQUE FAGET

What you need to know:

- The trial will be a boost of The African Union’s efforts to have perpetrators of crimes against humanity be tried in the continent.

- Mr Habre is accused of widespread political killings, systematic torture, thousands of arbitrary arrests and the targeting of particular ethnic groups.

The trial of Chad’s former dictator Hissene Habre before the African Court of Justice begins on July 20 in Senegal where he fled to after his downfall in 1990.

It will be a historic case since it is the first time in Africa for the special court to prosecute a former ruler of another State for alleged crimes against humanity.

Alleged perpetrators of crimes against humanity have historically been tried at the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague, Netherlands.

The trial will be a boost of The African Union’s efforts to have perpetrators of crimes against humanity be tried in the continent.

Mr Habre is charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture, and has been placed in pre-trial detention.

The journey to prosecute Mr Habre began on February 8, 2013 when the Extraordinary African Chambers were inaugurated in Dakar, Senegal.

POLITICAL KILLINGS

Judges at the Extraordinary African Chamber ordered his trial as one of the people “ most responsible” for international crimes committed in Chad between June 7, 1982 and December 1, 1990. On July 2.

“The visibility of the victims has helped to garner public support for the case and it makes it harder for Habre to portray himself as being persecuted by political forces,” Mr Reed Brody, a spokesperson for Human Rights Watch.

Mr Habre is accused of widespread political killings, systematic torture, thousands of arbitrary arrests and the targeting of particular ethnic groups.

A key step in building the case against Mr Habre was Human Rights Watch’s discovery of files kept by the former dictator’s political police, the Documentation and Security Directorate which documented the chilling atrocities committed against prisoners.

“Habre wasn’t a distant ruler who ignored the massive atrocities carried out in his name,” said Olivier Bercault, the principal author of the 2013 Human Rights Watch report.

“We found that Habre directed and controlled the political police, who tortured and killed those who opposed him or those who simply belonged to the wrong tribe,” Mr Bercault said.

Already, twenty top security agents of Mr Habre’s government were convicted on March 25, 2015 by Chadian courts for torture and murder charges.

According to Mr Brody, a court in Ndjamena in March convicted 21 of Mr Habre’s alleged accomplices and ordered $125million in reparations for victims, the building of a memorial, and transformation of the former political police headquarters into a museum.

“The Hissene Habre trial shows that it is possible for victims, with perseverance and resolve, to bring a dictator to court.

“This is a wake-up call to tyrants that if they engage in atrocities they will never be out of the reach of their victims,” he said.