Annan: How I got Kibaki, Raila to sign peace accord

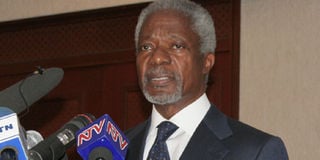

Former United Nations secretary general Kofi Annan. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- Mr Annan speaks of “childish obstacles” such as sitting arrangements which he faced in his mission to defuse “an existential threat to Kenya itself”.

- The Kenyan mediation is captured in one chapter of Mr Annan’s book, Interventions: A Life in War and Peace.

- The chapter, titled “Half a Million Rwandan Ghosts: Crisis in Kenya,” depicts President Kibaki’s negotiating team as more obstinate than Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s.

- This seems to give credence to Mr Miguna Miguna’s claim in his own book: Peeling Back The Mask, that President Kibaki took and took from Mr Odinga without giving back anything during the negotiations.

Former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan confronted President Kibaki with the alarming figures of Kenyans who had been killed in the 2008 post-election violence before the National Accord was signed.

In a book revealing behind-the-scenes events that marked the 39-day mediation period, Mr Annan also speaks of “childish obstacles” such as sitting arrangements which he faced in his mission to defuse “an existential threat to Kenya itself”.

He credits the accord for helping Kenya get a new Constitution, which significantly rearranges the power equation.

But he expresses disappointment that the old order still fought back in such events like inviting Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir during the promulgation of the Constitution and failure to prosecute those accused of planning and executing the post-election violence.

More obstinate

The Kenyan mediation is captured in one chapter of Mr Annan’s book, Interventions: A Life in War and Peace.

The chapter, titled “Half a Million Rwandan Ghosts: Crisis in Kenya,” depicts President Kibaki’s negotiating team as more obstinate than Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s.

This seems to give credence to Mr Miguna Miguna’s claim in his own book: Peeling Back The Mask, that President Kibaki took and took from Mr Odinga without giving back anything during the negotiations. (READ: Secret story of Raila’s relations with Kibaki)

Mr Annan says that he suspended the proceedings of the mediation team at the Serena Hotel in late February and decided to face President Kibaki when the number of the dead rose to 1,000. The talks, he says, had reached a make or break point.

“Mr President, over 1,000 people are dead. It’s time to make a deal,” he writes. “This was my last play,” Mr Annan continues.

“The game now had to end. We needed an agreement on the transformation of the Kenyan political system. Otherwise, the country would be unable to bear what seemed sure to come.”

Mr Annan says he feared the Kenya situation could reach the magnitude of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and decided to bring in more international pressure to push through the deal.

US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Tanzania President Jakaya Kikwete helped strike a deal between Mr Kibaki of PNU and Mr Odinga of ODM.

A deal was finally struck and was sealed by handshakes and signatures on the part of Mr Kibaki and Mr Odinga. “But it did not feel triumphant,” Mr Annan says of this diplomatic success. “It had taken far too long.”

Mr Annan writes of PNU’s reluctance to accept a compromise limiting the President’s power and sharing control of government ministries with ODM.

“The PNU side in particular was holding things back. If I walked away without a deal,” he writes, “it would be clear that Kibaki was to blame.” In the conflagration following the disputed 2007 election, “the dark side of Kenya had erupted,” Mr Annan observes.

The tribal violence that claimed more than 1,000 lives had exposed a terrible truth: “The ultimate governor of life in Kenya was not any rule of law but the rule of blood line.”

“Twin blades of inequality and crony-capitalist politics had long combined to shear deep grievances, resentment and desperate competition along Kenya’s ethnic contours,” Mr Annan writes.

“Corruption among politicians and the civil service had become a monster.” These core elements of the country’s crisis had to be addressed through structural reform of Kenya’s governance, Mr Annan came to conclude.

To be effective, he says, an agreement would have to be crafted to change the fundamentals of state power and “not just to move the chairs around on behalf of the political elites.”

But Mr Kibaki’s side was insisting on literally rearranging chairs as the negotiations entered a critical stage, Mr Annan recalls. He says he had proposed that he be seated between the two chief antagonists — Mr Kibaki and Mr Odinga.

But two top PNU operatives — Francis Muthaura and Uhuru Kenyatta — insisted that Mr Kibaki sits in the middle in his special presidential chair.

Sealed envelope

Such an arrangement signifying Mr Kibaki’s primacy would be unacceptable to the Odinga side and would short-circuit the negotiations, Mr Annan writes. Mr Annan’s frustration is evident as he refers to the “childish nature of these obstacles.”

He expresses satisfaction with the International Criminal Court’s actions in the case of Kenya and recounts his decision to pass along a sealed envelope to ICC Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo containing the names of Kenyans suspected of having orchestrated the post-election mayhem.

Mr Annan says it had become clear to him that the Kenyan government was not going to hold these individuals to account for their deadly actions.