Hopes fade for the landless after 45 years

Bob Odalo | NATION

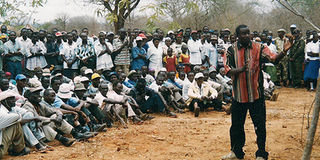

Former Kibwezi MP Kalembe Ndile known for fighting for the right of the landless addresses squatters in the constituency

What you need to know:

- From Kenyatta to Moi and now Kibaki, the landless of Kibwezi have seen their hopes turn to despair as a solution to their predicament fades with each day

They have seen governments come and go, each promising to find a lasting solution to their plight.

From Jomo Kenyatta, the founding president, to Daniel arap Moi and now Mwai Kibaki, the squatters of Kibwezi have seen their hopes turn to despair as more than 45 years after Independence a solution to their predicament appears to be fading with each passing day.

Former Kibwezi MP Kalembe Ndile has over the years remained one of the most vocal crusaders for the plight of squatters in Makueni.

He began to fight as an ordinary villager and land activist then continued as an elected councillor and county council chairman. When he was elected MP he took the squatters’ case to Parliament, earning himself the nickname Son of a Squatter.

When he left Parliament after losing the Kibwezi seat in 2007, more than 2,000 families were still squatting in Kibwezi.

“We thought there was a desire by the new government which came into being in 2003 to solve this problem, but with 2012 approaching I don’t see much being realised,’’ said Mr Ndile.

The history of the Kibwezi squatters is intertwined with the history of the Ngulia people said to have been the indigenous Akamba of Kikumbulyu.

They lived in Kibwezi before 1836 according to Lindblom and Hobley in their book Akamba of British East Africa.

They were forced to migrate during the great famine of 1836. Some went south to Rabai where the missionary Dr Krapf came across them in 1850, having lived there for over 15 years.

Others spread southwest and took up permanent residence in villages between Taveta and Lake Jipe in the Pare mountains and then crossed to Tanzania to Usambara up to Musi valley and the depression of Maramba.

However, a large number remained in Kikumbulyu, stretching from the Kiboko river in the north to Tsavo in the south and westwards to Kyulu ranges known in other quarters as Ngulia ranges.

According to a 2002-2006 policy research project by the Masongaleni Community organisation for Sustainable Development (Macosud ) when the East African Scottish missionaries led by Dr James Steward arrived in Kibwezi in 1891 the Ngulia Akamba were there, which is proved by documented agreements between the missionaries and the Ngulia under the rule of Kilundo in 1891.

Mr Jacobus Kiilu, who conducted the two-year research while Macosud chief executive officer, said the Ngulia, who form part of the biggest population of Kibwezi squatters, had their settlements centred around water points, water courses, hills, near raised rock masses and areas with tall trees like baobabs.

Trouble for the Ngulia came in the late 1890s and early 1900s when missionaries are believed to have influenced white settlement in Kibwezi.

“The arrival of the Scottish mission in Kibwezi was followed by the establishment of British Imperial East Africa and the Kenya Colony in that order. These institutions of the British empire initiated what was to become a long history of eviction and resettlement within the ancestral land of the Ngulia,” explained Mr Kiilu.

This included the need to create space for the white settlers’ estates, wildlife conservation and hunting grounds in Kikumbulyu. This was preceded by tactical evictions of the Ngulia.

“They were often made to believe that these institutions and subsequent organs of government were operating in order to facilitate development but they were wrong,” he said.

According to records, the establishment of the Tsavo West national park led to the eviction of the Ngulia from Tsavo river through Mzima Springs up to Mtito Andei river.

Following the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1902, the Akamba Ngulia were restricted within Kikumbulyu native reserve where they were occupying three blocks —Kyale near Kiboko river; Mbui Nzau around the Mbui Nzau hills near Kibwezi; and Kyulu block along the Kyulu ranges up to Mtito Andei river.

Kyulu block was reportedly the biggest with a population of more than 5,000 people.

Native reserves

Research shows that by the end of World War One, the new native reserves were fully enforceable.

“All the land elsewhere became Crown land and any Ngulia going there for habitation, hunting or bee keeping faced instant prosecution and eviction without compensation,” states the research document by Macosud.

When this was happening the colonial government was alienating and registering their ancestral land along the railway line to Europeans and Asians on terms ranging from freehold regime for the Scottish missionaries to leasehold for the Manooni sugar estate.

The removal of the Ngulia from their ancestral lands intensified in July 1932 when the colonial district commissioner visited Kikumbulyu reserve on a regular tour of Kyulu location.

Records show that the DC made a personal observation that Akamba from Kyulu block were suffering due to drought and said the best way out was to move them from Kyulu to Kyale near Kiboko river.

The Carter Land Commission, in its 1932 report, stated that it fully agreed with the PC and recommended that the Kyulu people be moved north of the railway, that the Kyulu sub-location should revert to Crown land, and that the 512 square miles of Crown land be made native reserve.

These implementations were recommended between 1935 and 1936 causing the second massive eviction of Kamba Ngulia from Kyulu.

According to the Macosud document, the status quo was maintained upto the time of Independence and beyond. Lack of security on land tenure for the Ngulia has remained a persistent problem more than 45 years after Independence.

The gazetting of Ngai Ndethya game reserve in 1976, covering a large settled area in Mtito Andei, was another setback for these people.

In the 1980s Kyulu National Park was created from Chyulu conservation area and lives and property were lost in the process.

More than 5,000 households were made homeless from 1987 and it was not until 1992 that the government started settling some of the affected squatters in Masongaleni, Kibwezi, Kiboko ‘A’ and Kiboko ‘B’ settlements schemes.

This exercise was hit by setbacks as well-connected individuals and politicians grabbed huge chunks of land which they dished out to their friends, relatives and cronies leaving many landless people to live as squatters in Kibwezi.

Mr Kiilu, the former Macosud chief executive, said the solution lay with the yet-to-be-formed National Land Commission which will be better placed to address all the social injustices.