Assault on African leaders creating ‘land without heroes’

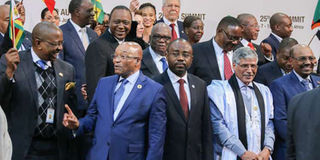

African Heads of State and Government during the official opening of the 25th African Union Summit at Sandton International Convention Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa. PHOTO | PSCU

What you need to know:

- The on-going assault on Africa’s new generation of leaders fits like a glove into the epic narrative of the “rise and fall” of Africa’s “four generations” of leaders in the post-colonial era.

- This subtle narrative, which has defined the image of Africa across generations, has morphed through four stages.

- The first stage coincides with the rise of “the new generation of nationalist leaders” from the late 1950s and 1960s, the moment of our George Washington, Mahatma Gandhi and Simon Bolivar, when the gallant nationalists, pan-Africanists and founding fathers of modern Africa ushered the continent to freedom.

- In came the second generation of the “big men” of African politics during the first two decades after independence. Epitomised by Congo’s Mobutu Sese Seko, Uganda’s Idi Amin and Central Africa’s Jean-Bédel Bokassa, this generation presided over the bloodiest phase and democracy’s darkest age in Africa.

- Alongside the third generation is the rise of Africa’s fourth generation, the most assertive since the days of Patrice Lumumba, Ahmed Sekou Toure and Kwame Nkrumah in the 1960s.

On March 12, 1998, the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations’ sub-committee on African affairs held a rare hearing on “Democracy in Africa: The new generation of African leaders.”

Prefaced by the Jeffersonian concept of “just powers from the consent of the governed,” the session popularised the idea of “a new generation African leaders” and their policies and tore down the iron curtain “afro-pessimism” that hitherto characterised the image of Africa and its leadership in the academy, media and the corridors of power in Western capitals.

In the intervening decades, the global image of Africa rose meteorically from what the Economist magazine once rubbished as “a hopeless continent” to what it later celebrated as a “hopeful Africa rising.”

South Africa’s Presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki enchanted the new age of “African Renaissance”.

Nearly two decades later, the recently-concluded African Union Summit on January 21-31, 2016 heralded an end of this honeymoon for African leaders. A rancorous debate on the role of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in Africa’s conflict zones, the festering situation in Burundi and the challenge to the AU forces by terrorism are giving rise to a new wave of neo-pessimism in Western capitals and media — and rather expectedly, from opposition groups within.

The on-going assault on Africa’s new generation of leaders fits like a glove into the epic narrative of the “rise and fall” of Africa’s “four generations” of leaders in the post-colonial era.

Inexorably, this narrative has left Africa as “the land without heroes” usually identified with slave or colonised communities where the masters or colonisers determine who is and who is not “a hero”.

Discernibly, this subtle narrative, which has defined the image of Africa across generations, has morphed through four stages.

The first stage coincides with the rise of “the new generation of nationalist leaders” from the late 1950s and 1960s, the moment of our George Washington, Mahatma Gandhi and Simon Bolivar, when the gallant nationalists, pan-Africanists and founding fathers of modern Africa ushered the continent to freedom.

NO LOVE LOST

Among these heroes were Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. Also in this pantheon of heroes were pan-African thinkers like America’s W.E.B. Du Bois and Trinidad’s George Padmore — who later returned to Africa and died here.

Expectedly, there was no love lost between Africa’s founding fathers and its erstwhile colonisers — who were widely accused of underwriting the project of demonising, brutally killing or violently removing the best of this generation from power.

In came the second generation of the “big men” of African politics during the first two decades after independence. Epitomised by Congo’s Mobutu Sese Seko, Uganda’s Idi Amin and Central Africa’s Jean-Bédel Bokassa, this generation presided over the bloodiest phase and democracy’s darkest age in Africa. They genuinely loved — and were loved right back by — the white knights of the Cold War era who used them to paint the most grisly image of Africa.

HOPE FOR DEMOCRACY

It was America’s second post-Cold War President, Bill Clinton, who christened and popularised the ensuing third generation as the “New generation of African leaders” during his trip to Africa in March 1998.

To be sure, Clinton did not identify the African leaders by name, but the names of Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Paul Kagame of Rwanda, Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia, Isaias Afewerki of Eritrea, Jerry Rawlings of Ghana, Joaquim Chissano of Mozambique and Thabo Mbeki of South Africa came up.

But Clinton placed hope for democracy and economic reforms on this generation who successfully led the bush rebellions that removed from power Africa’s worst leaders, returned the continent to relative stability and economic growth, and put in place the most effective social programmes, including national responses to HIV/Aids in Africa.

Soon, this optimism was lost and these leaders were spoken of as the “fallen angels” ostensibly because they “failed to deliver adequate democracy, peace and development, and they overstayed in power.

Alongside the third generation is the rise of Africa’s fourth generation, the most assertive since the days of Patrice Lumumba, Ahmed Sekou Toure and Kwame Nkrumah in the 1960s.

Africa’s fourth generation of leaders has risen to the helm of power against the backdrop of two positive developments.

First is the radical geo-political arising from the emergence of BRIC powers — Brazil, Russia, India and China — and rise of the global south to challenge the West in the struggle for global hegemony in the 21st century, which has expanded space for weaker African powers in global governance.

Second is the refurbishing of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) into the African Union as a more potent platform for reconstituting Africa’s collective power in the new global geo-politics.

MAKING BOLD CHOICES

This generation is making bold choices to use the hardest power against terrorism, use soft power to mediate Africa’s most protracted ethnic conflicts in Burundi and South Sudan and threatened to pull out of the ICC en mass for putting stability at risk in Africa’s fragile nations.

But the honeymoon for the fourth generation has been cut short too soon.

In Nigeria, the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) vowed on September 9, 2015 that it would not hang the official portrait of the newly-elected President Muhammadu Buhari.

And in Kenya, the Governor of Siaya County in the opposition’s stronghold of Luo Nyanza, Cornel Rasanga, called on all opposition governors to replace the portrait of Presiden Uhuru Kenyatta with that of opposition leader Raila Odinga.

A subtle mix of “rogue opposition” groups across Africa and resurgence racism abroad poses the greatest threat to African leaders and peoples globally. Africa needs to defend its heroes; a people without heroes are slaves.

Professor Kagwanja is the Chief Executive of the Africa Policy Institute