Give girls a chance, send them to school

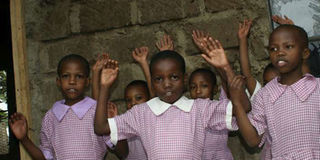

Pupils of Our God Girls Educational Centre Githurai. Adolescent and young girls are four to six times more likely to contract HIV than boys of a similar age. FILE PHOTO | ANTHONY OMUYA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The narrative has not changed. The village and low-income urban settlements remain the chief suppliers of domestic help to pseudo middle-class city dwellers.

- The law needs to be enforced stringently against people who employ children because this is child labour, which is illegal.

My first contact with Atieno Yo, the timeless poem composed by Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye that highlights the plight of girls in Kenya who become mothers at a tender age and, therefore, miss out on living productive lives, was back in high school.

It was made mandatory reading by my literature in English teacher, one Mrs Okware, who no doubt appreciated the need to train young boys to appreciate the importance of empowering girls.

Many male members of the current Parliament did not attend those classes, and if they did, then Atieno Yo went right past them.

I know this because I watched them frustrate the passing of the two-thirds Gender Bill in the House. Two times!

But I digress. I am writing this piece because I am a disturbed man. In fact, I have been disturbed for a long time now for the simple reason that we as a nation have decided that girls in Kenya can only achieve quality education, financial independence, and general success by chance, not through systemic policies tailored to guarantee them these things.

Do not get me wrong, the government of Kenya probably spends a large part of its budget annually in the provision of free primary education and subsidising secondary schooling.

However, that does not mean that every young Kenyan of school-going age is in school.

One of the main reasons for this must be our collective acceptance that young girls who have dropped out of school are fair game for employment as domestic help.

Growing up in the village, it was always a source of envy for young boys when girls who were our playmates were suddenly yanked from our midst and sent to the towns and the big city to work.

In our minds, the big city, which we had only read about in books or heard about on radio, was hugely glamorous.

It did not occur to us that we were the lucky ones because we were left behind and therefore continued with our schooling.

SAD STATE

The narrative has not changed. The village and low-income urban settlements remain the chief suppliers of domestic help to pseudo middle-class city dwellers.

Do education policy makers and stakeholders realise that one of the reasons for low transition rates for girls from primary to secondary school is the ready job market for domestic workers?

It gets worse. According to the 2015 estimates, 46 per cent of all new HIV infections are among adolescents and young people.

Further, adolescent and young girls are four to six times more likely to contract HIV than boys of a similar age.

There are several reasons for this, but one of the main ones is that girls who drop out of school and begin to live like adults when they are not prepared for this responsibility become vulnerable and, therefore, easy prey for sexual predators. Many become victims of their employers.

I would like to live in a Kenya where every young person is guaranteed an opportunity to get an education and succeed in life.

Where girls are not made unnecessarily vulnerable to the risk of HIV because we would rather they served us in our homes than take them back to school.

The law needs to be enforced stringently against people who employ children because this is child labour, which is illegal.

The current curriculum review should consider the options that can be made available for young Kenyans who drop out of school and would want to attend flexible programmes that can enable them to gain skills.

This requirement should be made a part of the curriculum or the education policy and not be left to be haphazardly implemented, as has happened with programmes such as adult education.

Mr Ohaga is the head of communication at the National Aids Control Council. [email protected]