Is Kenya being isolated in East Africa? Ask another question

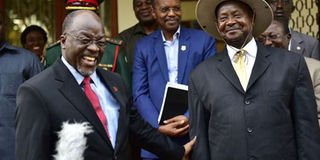

Tanzania President John Magufuli (left) with President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda shortly after the bilateral meeting at Arusha State Lodge on February 30, 2016. There have been cries that Kenya is being “isolated” by the other East African countries especially after Uganda snubbed several joint projects in favour of Tanzania. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

One of the fanciest hospitals and East Africa’s first tele-medicine hospital is Butaro, in western Rwanda. It was built in one of the most far-flung parts of the country.

There was criticism when the hospital was being built, with accusations that it was a “waste” to locate it in the wilderness and that it would turn into a white elephant.

Shortly after opening, hundreds of Ugandans swept across the border, travelling to be attended to at the hospital.

There has been a lot of hand-wringing, and even alarm, in Kenya since Uganda decided to route its oil pipeline through Tanzania and Rwanda gave up the standard gauge railway and also decided to go with a line through Tanzania.

There have been cries that Kenya is being “isolated” by the other East African countries.

Surprising, really, because one would have thought that after so many years as the region’s leading economy, Kenya would be a little more confident than it is sounding.

But there is something else. The focus on big infrastructure has partially to do with patriotic vanity and even nationalist ego rather than how countries in the region fuel each other’s development.

For example, one of the fanciest hospitals and East Africa’s first tele-medicine hospital is Butaro, in western Rwanda. It was built in one of the most far-flung parts of the country.

There was criticism when the hospital was being built, with accusations that it was a “waste” to locate it in the wilderness and that it would turn into a white elephant.

It might well have, except there was something no one had factored in during the plan.

The hospital is not far off from Uganda, and that region of Uganda had no decent hospital.

Shortly after opening, hundreds of Ugandans swept across the border, travelling to be attended to at the hospital. That, and other local factors, changed the story of Butaro.

Near my hometown in eastern Uganda, a low profile Italian Catholic order built a small eye hospital for the community. Many people in the area still do not know that the hospital exists.

Within weeks of its opening, hundreds of Kenyans were crossing the border from the western part of the country.

Exploiting the exchange differential of the Kenyan shilling against the Ugandan one, the hospital ended up with deep-pocketed patients it had not planned for.

Soon Kenyans made up 70 per cent of the patients, upending the social goals of the missionaries and disrupting their economic model — although they were not complaining too much.

Then I went to visit a friend who is a businessman there. He is developing an interesting farm and has invested quite a bit in water.

He had dug a deep well and when I was there he was working on installing a small wind turbine to drive it. I thought it had cost him a lot of money.

No, it had not. He had got a chap “across” the border in Nakuru, Kenya, to set it all up for him for Sh100,000.

He is also known to supply the sweetest mangoes in that part of the world. And that provided the biggest surprise.

I thought he had a big mango plantation. However, when I went to his walled-off house, he led me to the backyard, where there were a handful of trees, standing at about six feet tall and weighed down by juicy shiny fruit.

It was all thanks to an innovative bloke somewhere in a village in Machakos, he explained.

He is the one who came across and grafted something on his local mango trees.

I asked how he knew about a Kenyan fellow in rural Machakos who had golden mango fingers, so to speak. He just chuckled.

These are just a few of the hundreds of these stories.

These are the things that really create wealth for most families and improve the standard of their lives.

The point is that governments and institutions hardly script or shape development as much as they think.

And it is these markets and business relationships that are shaping livelihoods in the region.

The infrastructure that is driving the narrative of Kenyan “isolation” has very little, if any, impact on that universe.

There is a reason for this. We have a disconnect, where the commentary about the East African economy is by people who do not themselves trade regionally.

While working on a writing assignment on East Africa once, I asked someone who has made a fortune trading in the region about the most important thing he thought was critical for him to continue flourishing.

I thought he would talk about railways, dual carriageways connecting countries in the region, and so on. He did not.

He said; “We have enough roads. All the governments in East Africa need to do is keep the borders working for 24 hours”.

The author is editor of Mail & Guardian Africa. Twitter: @cobbo