After rapid progress, Kenya has hit plateau in path to real democracy

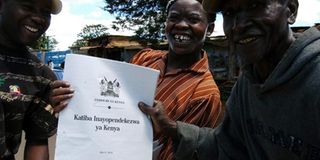

Nyeri residents with copies of the 2010 Constitution. Devolution ordained by the Constitution has established an important means for counteracting the central ill of the Kenya state from the colonial era to the present: authoritarian, clientelistic executive abuse clothed in impunity. FILE PHOTO | JOSEPH KANYI | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- I realise that even with the perspective of career-long interest in Kenya, observations based on such a short visit must remain very tentative and provisional.

- Kenya’s print media explore serious issues, accept opinion pieces, and confront the shortcomings of ruling regimes with a bluntness and vigor that makes leading papers in my own country seem staid and restrained.

- Majimbo was instituted on behalf of ethnic and racial minorities to counterbalance a feared Kanu government while devolution has been established on behalf of majorities to check any future majority rule.

This essay reflects on my first visit to Kenya since just after passage of the 2010 Constitution, this past month, just fifty years since my first visit to Kenya in the Spring of 1965, the first of many in the intervening years.

As someone with a research and policy focus on democracy, I was keen to get a first hand sense of Kenya’s progress toward becoming a democratic state, a process that began when I was USAID’s Regional Democracy and Governance Advisor for Eastern and Southern Africa, based in Nairobi in the mid-1990s.

I realise that even with the perspective of career-long interest in Kenya, observations based on such a short visit must remain very tentative and provisional.

My overarching impression is that while, on the one hand, Kenya appears to be more democratic than ever, on the other hand, the country’s democratic momentum has reached a plateau.

I think Kenya’s emergent democracy exhibits weaknesses, and is vulnerable to further weakening, in ways that call into question how democratisation is designed and promoted by those of us in the academic community as well as by policymakers.

On the one hand, Kenyans practice democracy vigorously, for more than at the outset of its democratic era in the mid-1990s and in ways that would have been hard to imagine in the mid-1960s.

Kenya’s print media explore serious issues, accept opinion pieces, and confront the shortcomings of ruling regimes with a bluntness and vigor that makes leading papers in my own country seem staid and restrained.

The behavior of senior members of the governed is called into question by the media and by members of Parliament and it has been heard and responded to with the current reshuffling of cabinet positions.

Devolution ordained by the Constitution has established an important means for counteracting the central ill of the Kenya state from the colonial era to the present: authoritarian, clientelistic executive abuse clothed in impunity.

MAJIMBO

The rule of law often seems not to get the emphasis it deserves in democracy promotion, taking a backseat to term limits and free and fair elections, indispensably important though both are.

I am persuaded that Kenya’s reconstituted judiciary has achieved more independence of the other branches of government and brought more judicial integrity under the leadership of Chief Justice Willy Mutunga than has existed in the past.

A noteworthy feature of Kenya’s 2010 Constitution is the similarity in some of its key provisions to the independence Constitution that the British Government more or less imposed on Jomo Kenyatta’s Kanu as a condition for allowing independence to occur.

Majimbo was instituted on behalf of ethnic and racial minorities to counterbalance a feared Kanu government while devolution has been established on behalf of majorities to check any future majority rule.

An upper chamber of Parliament was established to check the lower house in both Constitutions for the same purpose.

With the possibly important exception of devolution, I have discerned few initiatives to take Kenya’s pursuit of a democratic state to the next level of quality and consequence.

And I see important threats on the horizon to Kenya’s ability to sustain its existing levels of democracy including widespread corruption and widening of ethnic divides and partisanship have, if anything, deepened since the passage of the 2010 Constitution.

CONSTITUTIONAL CULTURE

All this emphasises what has been has been a routinely overlooked dimension of constitutional implementation in general and of the Kenya Constitution in particular.

Any constitution, but especially the Kenya Constitution, which is aspirational in so many of its provisions, requires cultivation and widespread diffusion of a supportive constitutional culture, more than just realisation of its provisions in law.

A constitutional culture comes into being when elites and ordinary citizens alike internalise the difference between liberty and license and intuitively respect it practice, and when rooted beliefs in membership in a polity of political equals supersede those of colonially reinforced ethnic divides.

There is no is no substitute for cultivation and visible models of the practice of a constitutional culture the deeper and more extensive contrary pre-existing practice.