Kenyan writers fail when they don’t point out ills in society

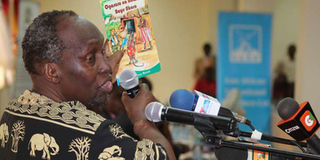

Prof. Ngugi wa Thiong'o shows a copy of a story book written in vernacular during his public lecture at Kisii University on August 31, 2015. PHOTO | BENSON MOMANYI | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Instead of fuelling the creative juices of our writers, the mega-scandals in the country have produced an eerie silence.

- The writings of Ngugi, for instance, helped me understand why, despite our so-called independence, Kenya was unable to fully liberate itself from the clutches of colonialism.

- Some of the best writing in Kenya happened during one-party rule and at a time when it was life-threatening to do so.

One would think that with all the shenanigans and horror stories of mind-blowing corruption in the government and in the public and private sectors, Kenyan writers would have enough material to write a book or two on the state of the nation.

However, instead of fuelling the creative juices of our writers, the mega-scandals in the country have produced an eerie silence.

Why are Kenyan writers so quiet in the face of so much dysfunctionality? Where are writers like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, whose books Detained and Decolonising the Mind shifted the consciousness of entire generations?

Where are people like Wahome Mutahi, who emerged from jail and then satirised his own incarceration at the hands of a dictatorship? Has any one of the younger generation of Kenyan writers had a profound, ground-shifting impact on the national psyche? Unfortunately, no.

Some of the best writing in Kenya happened during one-party rule and at a time when it was life-threatening to do so. It was a time when writers felt they had a responsibility to document the ills in society and to hold a mirror to the world. They understood that literature had the power to heal and repair societies.

The writings of Ngugi, for instance, helped me understand why, despite our so-called independence, Kenya was unable to fully liberate itself from the clutches of colonialism. Our current crop of writers rarely offer such insights.

Perhaps the abnormal has become so normalised that it has stunted the imagination of those who have a duty to point out to the emperor that he has no clothes.

Maybe, as with every sector in Kenyan society, writers have become acutely ethnocentric and, therefore, view society through the prism of tribe. Has tribal loyalty or misplaced nationalism prevented them from dissecting Kenyan society too harshly?

Or perhaps, like many Kenyans, they suffer from cognitive dissonance; they have not only accepted and moved on, but have convinced themselves that all is as it should be. Life is beautiful, la-di-da.

These writers should heed the words of Frantz Fanon, who wrote: “The future will have no pity for those men (and women) who, possessing the exceptional privilege of being able to speak words of truth to their oppressors, have taken refuge in an attitude of passivity, of mute indifference, and sometimes of cold complicity.”

PILLARS OF INTEGRITY

In a provocative literary column in the Saturday Nation, Dr Evan Mwangi noted that those who claim to be the pillars of integrity in this society are so deeply embedded in corrupt practices that they have lost credibility. He wrote: “Kenyan families remain a sly political social unit. In most cases, the conjugal partner of an anti-corruption crusader works for the corrupt government being criticised.

The family eats from both opposing sides, giving only lip service to anti-corruption efforts. In the same vein, the most vocal lawyers against corruption also represent obviously corrupt government functionaries.” Are our writers similarly corrupted?

Do not get me wrong. It is not that Kenyans are not writing. Yvonne Owuor’s lyrical masterpiece, Dust, is a brilliant exposé of the historical injustices that have silenced large sections of Kenyan society. There are also sensitive and courageous writers like Patrick Gathara, Aleya Kassam, and Wandia Njoya, who put themselves out there every day to tell it as it is.

However, the latter are often not viewed as writers per se, but as political analysts, social commentators, or bloggers. Then there are the Twitterati, who put out clever one-liners but do not have the will or discipline to write a whole book or essay.

I believe one of the reasons that today’s writers are not as prolific as their predecessors is that they have become “NGO-ised”, that is, dependent on donor funding. There was a time when writers wrote not for money or fame, but simply because they felt that if they did not write, they would die. The lucky ones got published. Those not so lucky kept writing anyway.

These days it is hard to find a writer who does not seek donor funding, grants, or advances before beginning a writing “project” or to participate in writing “workshops”.

The “NGO-isation” of writers has had the net impact of stifling creativity and depriving writers of their intellectual independence.