Meaning of words lie on what they connote

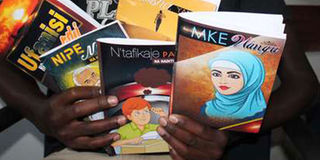

A poem’s true “meaning” lies, not in what the words denote, but only in what they connote. PHOTO | STANLEY KIMUGE

What you need to know:

- As with Ciardi, please note that the real significance of a poem is not what it means literally but only how it means in figurative terms, only how its motion affects your emotion.

What does it look like whenever a “…hospital is flooded with patients...”?

I plucked the words in quotes from the Daily Nation of January 2.

Literally, they meant that the hospital had admitted so many patients that the patients began to appear to flow like a liquid.

Indeed, that should have made it a good figure of speech, an effective metaphor.

For the verbs to flow and to flood have the same etymological root.

To flood is to overflow in the same way as happened to the Tigris, the Euphrates (and probably the Indus), as we read in Jewry’s book called the bible.

Of liquids and gases, to flow is to move from one place to another.

It is in the same way that words may flow from someone’s mouth to someone’s ear – like the flood of words from the mouth of many a Kenyan politician.

Thus if you are imaginative enough, a language may begin to appear to you like a river (like a kind of Nile for the poetry-given Nilotic peoples of north-eastern Africa).

A speaker may be so fluent in one of those languages that, from her or his mouth, the words may appear to flow like the Yala or the Kuja, with all the cataracts and doldrums which those historic “burns” may imply – “burn” being an old Celtic word for a river.

Concerning speech, then, the adjective fluent describes that which flows (including out of the mouth) with the ease of royalty and wit such magic as might have appeared to Gerard Manley Hopkins – the 19th-century English lyricist – as “…gay-gear, going-gallant, girl-grace…”

FIGURATIVE

There, the poet seems to be telling his readers that, like life itself – which is the inspirer of all realistic poetry – a poem is meaningful only in motion; that the way a poem moves is, indeed, its only true significance; and that a poem’s motion should strike the reader with the “…gay-gear, going-gallant, girl-grace…” of any good poem.

That – as the Italian-American poetry critic John Ciardi has put it in poetry criticism – is how a poem means.

As with Ciardi, please note that the real significance of a poem is not what it means literally but only how it means in figurative terms, only how its motion affects your emotion.

A poem’s primary meaning, then, lies in how its motion interacts with your feelings, not how it affects your intellect alone (even though, in human beings, the intellect and the emotion are always essentially linked in functional terms, which is why Ciardi calls his book, not What Does a Poem Mean?, but How Does a Poem Mean?

Ciardi was born into the Mediterranean people whom we know as Italians, for whom life is one whole opera piece, to be recited, danced to, lived, and thoroughly enjoyed.

For, contrariwise – as Tweedledee used to tell Tweedledum in Alice in Wonderland – or was it the other way round? – a poem’s true “meaning” lies, not in what the words denote, but only in what they connote.