Moi, Njonjo and the Indian witchdoctor who cursed Kenya

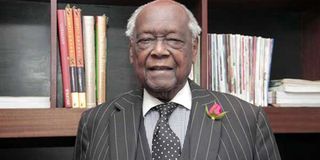

Former Attorney-General Charles Njonjo during an interview at his Westlands office on May 15, 2015. PHOTO | DIANA NGILA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The Muthemba case flopped but it would resurface at the Njonjo inquiry and was used to link the former AG to the 1982 abortive coup.

- The former chairman of the judges and magistrates vetting board recalls advising Mr Moi and then Attorney-General James Karugu against having Mr Muthemba charged with treason, citing weak evidence.

- Mr Rao alludes to the personal insecurities that made the new president and the people around him uncomfortable with the Kenyatta-era powerman.

The fallout between Kenya’s second president Daniel arap Moi and his hitherto one of the most trusted allies, Charles Njonjo, in the early 1980s remains something of a mystery to date.

Well, the commission of inquiry into the Njonjo Affair concluded that the Kenyatta-era Attorney-General plotted to overthrow the man he is widely believed to have single-handedly installed as president against a strong opposition by a powerful Kikuyu elite that wished to see one of their own succeed Jomo Kenyatta.

But how did Mr Njonjo get off so lightly — a presidential pardon only restricting his active involvement in national politics but allowing him to continue pursuing his business interests, for example?

And this at a time when many African dictators did very nasty things to their perceived opponents, including jailing them, sending them into exile or even eating their flesh! Was Mr Njonjo even guilty of plotting against Mr Moi in the first place?

Veteran lawyer Sharad Rao, who prosecuted the case in which Njonjo’s cousin Andrew Muthemba was implicated in a plot to steal weapons and testified at the commission of inquiry, just falls short of calling the whole thing a farce in his new book, Indian Dukawallahs.

CHARGED WITH TREASON

The book tries to document the community’s contribution to Kenya’s politics and economy since the first group of 350 men arrived in a dhow in Mombasa in 1895 to work on the Kenya-Uganda railway.

The former chairman of the judges and magistrates vetting board recalls advising Mr Moi and then Attorney-General James Karugu against having Mr Muthemba charged with treason, citing weak evidence.

He, nevertheless, proceeded to prosecute the case “at Moi’s insistence and despite Karugu’s reluctance”. The Muthemba case flopped, predictably, but it would resurface at the Njonjo inquiry and was used to link the former AG to the 1982 abortive coup.

So what exactly caused the personality feud that transformed the Moi government into a repressive regime?

Like many commentators before him, Mr Rao alludes to the personal insecurities that made the new president and the people around him uncomfortable with the Kenyatta-era powerman.

Speculation that visiting US Vice-President George Bush spoke about Mr Njonjo as a candidate for the Number Two position here reportedly alarmed Mr Moi’s confidants.

But the other rumour Mr Rao refers to in his book, published by Free Press Publishers, has a tragic humour about it. It goes that a fraudulent Indian astrologer called Chandra Swami identified a number of the Big Man’s associates, including Mr Njonjo, during a consultation session.

To his credit, Mr Rao doesn’t hide his closeness to and adoration for the former AG, praising him for having been a strong defender of the European and Asian communities.

Jack Otieno is the chief sub-editor of the Business Daily newspaper: [email protected]