Tough task of putting Mumias Sugar back on profitable path

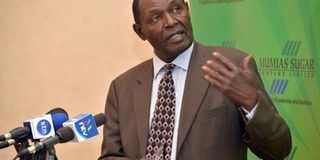

Mumias Sugar Company acting chief executive officer Coutts Otolo during a media briefing on the company’s financial performance in Nairobi on September 11, 2014. The listed miller suffered Sh2.7 billion loss for the year ended June 2014. It had recorded Sh1.6 billion loss in 2013. FILE PHOTO | SALATON NJAU |

What you need to know:

- Cash-starved firm will this week receive Sh500 million bail-out package.

Had the government not acted by pumping in Sh500 million into the troubled Mumias Sugar Company and by shaking up its top management, the country’s largest sugar manufacturer was clearly headed for receivership.

Away from the limelight, the company’s lenders were threatening to appoint a receiver to run its affairs.

Lately, the pressure from lenders has been mounting especially after a committee of lenders released an independent business review of the company.

That review, while concluding that Mumias Sugar was still a positive cash-flow company, made it clear that a successful turnround was only possible after a complete shake-up of its top management and board.

“Unless this is done, any debt restructuring plan put forward will not have credibility with lenders,” said the report.

This past week, the government started by re-advertising all the top jobs in the company.

This will be the second time the company is replacing its executive suite in less than six months.

Most significant, the lenders have insisted that the government, the largest shareholder, should consider bringing in a strategic investor or a contracted manager with a strong track record in the sugar industry to take control of the company and rid it of systemic corporate corruption.

STRATEGIC IVESTOR

It remains to be seen how far the government is prepared to go in implementing this demands.

Still, whether merely replacing the top management and board will work remains debatable considering that systemic corporate corruption is the problem.

Indeed, the fraudulent activities that have brought the company to its knees were the massive irregularities in the marketing, distribution and transportation of sugar.

The company’s top managers behaved like reckless cowboys. And the report highlights a catalogue of cases of manipulation of after-sales discounts, duplicated credit notes resulting in customers enjoying double discounts, post-sales discounts and discounts above the stated limits.

The company lost billions in these irregular transactions.

The report by the forensic auditors also revealed cases where transporters were diverting goods meant for inter-warehouse transfers.

Irregularities also centered around futures contracts, a system where distributors would advance money to the company in exchange of future supply of sugar at discounted prices.

It allowed distributors to bet on the upward movement of sugar prices, allowing them to pocket millions through exploiting anomalies in the market.

And, because of the dominant place of Mumias in the sugar sector, the discounts would create distortions in the market for sugar in the whole country.

The report painted a picture in which a tiny elite of distributors had more or less captured the company’s sugar marketing and distribution system, manipulating situations and routinely locking the company into lopsided deals and contracts.

The clout and influence of the distributors over the company is born out by statistics from the report by KPMG.

According to the independent business review by KPMG, Mumias Sugar Company was in a position in which it was badly exposed to the risk of sabotage by its distributors because of risk concentration.

SIX CUSTOMERS

The statistics show that almost 65 per cent of all sugar sales come from six customers who, incidentally, also double as distributors and transporters.

The upshot is an environment where the few distributors are able to collude to dictate prices and engage in other restrictive trade practices.

In their report, the auditors make a strong case for diversification of distributor channels by the company.

Is control over Mumias by the powerful clique of distributors about to be dismantled?

That remains to be seen.

It is understood that last month, as the company was struggling to raise money to re-open the factory, the incumbent management and board quietly decided to go back to a committee of distributors and signed futures contracts deals worth Sh1.6 billion, giving the distributors a 12.5 discount on current market prices.

The decision raised eyebrows within government, with critics pointing out that the Mumias management had returned to its old ways.

Insiders believe this new deal is what provided the urgency to move on the company’s top managers.

A consortium of lenders known as the ethanol group is also said to be up in arms after they found out that cash from sales that is ring-fenced and dedicated to service the ethanol loan had been diverted.

It is too early to predict how things will evolve. Removing the board may be problematic considering that Mumias is a listed company.

What is clear, however, is that the lenders who are eight in number will become more and more powerful in deciding the pace, direction and fortunes of the company.

The company currently has borrowings totaling a whopping Sh6.2 billion comprised of Sh 4.6 billion term loans and Sh1.6 billion in working capital facilities that it is currently unable to service.

In addition, the company owes approximately Sh5 billion to other creditors including outgrowers (Sh424 million), Kenya Revenue Authority (Sh2 billion). and customers and distributors Sh533 million.

Kenya Power is owed Sh47 million but has also claimed Sh953 million as penalties for purported failure to supply power under a power purchase agreement the two parties signed several years ago.

Established in 1971, Mumias is currently 20 per cent owned by the government.

In recent years, it has undertaken several expansion projects, venturing into new product areas such as power, ethanol and bottled water production.

In order to finance this expansion, it borrowed money from several lenders.

As an initial step to any restructuring of the company’s debt, the lenders insisted on an independent business review to confirm if the company is viable as a going concern.