Ruling a call to Judiciary back to the drawing board

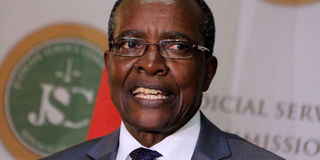

Chief Justice David Maraga addresses reporters on May 16, 2017 at the Supreme Court building after his deputy Philomena Mwilu was sworn-in to represent the Court in the Judiciary Service Commission. The new Constitution took a slightly different approach in relation to the powers of the High Court. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The judgment of the Supreme Court resolves an outstanding issue that has paralysed the administration of justice.

- Through a long tradition predating the new Constitution, industrial disputes were handled by the Industrial Court.

- The ELC and the ELRC are regarded as specialist courts and have fewer judges than the mainstream High Court.

The Supreme Court last week set aside a judgment in which the High Court had upheld a death sentence against three persons after they were found guilty of violent robbery and rape by a magistrate in Malindi.

However, the Supreme Court disallowed the judgment of the High Court, which the Court of Appeal had also set aside on first appeal, because one of two judges who heard the appeal was from the Environment and Land Court, rather than the mainstream High Court.

CONSTITUTION

The judgment of the Supreme Court resolves an outstanding issue that has paralysed the administration of justice, which relates to the jurisdictional limits of the High Court and the courts of equivalent powers whose establishment the new Constitution authorised.

But there is still pending for decision before the Court of Appeal another appeal that questions whether it is lawful for magistrates to hear land cases.

This problem arises from the manner in which courts have interpreted the arrangements in the new Constitution concerning the judicature.

Under the previous Constitution, the High Court was a superior court of record with unlimited original jurisdiction over civil and criminal cases.

INDUSTRIAL DISPUTES

The new Constitution took a slightly different approach in relation to the powers of the High Court.

While, together with the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal, the High Court is one of the superior courts, the new Constitution allows Parliament to establish “courts with the status of the High Court” to hear and determine disputes relating to employment and labour relations, and also the environment and the use of land.

Through a long tradition predating the new Constitution, industrial disputes were handled by the Industrial Court, which was not considered a part of the Judiciary, and which therefore provided a unique diversion for this category of disputes.

LABOUR RELATIONS COURT

Although it carried itself as a court of equivalent status as the High Court and although its officials were referred to as “judges”, the Industrial Court was only an administrative tribunal and its officials were not judges in any true sense.

All that the new Constitution did was to provide a mechanism for giving legal effect to a factual situation in which the Industrial Court had come to be regarded as the equivalent of the High Court.

Legislation deriving from the new Constitution has now established the Employment and Labour Relations Court (ELRC), which replaced the Industrial Court.

While the jurisdiction of the Industrial Court covered only industrial disputes, cases involving trade unions, leaving out ordinary employer/employee disputes, which were still subject to ordinary judicial mechanisms, the ELRC now entertains employer/employee disputes as well.

CONVICTION UPHELD

Because the Constitution says so, ELRC judges are proper judges, equal in status with judges of the High Court.

Legislation has also established the Environment and Land Court (ELC), also equivalent to the High Court in status.

Thus, the “High Court” now consists of three parallel but equal streams, being the original High Court as a generalist court that has carried on from the old Constitution, the ELRC and the ELC as two special-jurisdiction courts.

When recruiting judges, and although they have equal status, the Judiciary does so by reference to which court they are going to serve in.

The dispute that the Supreme Court settled last week arose when, in 2013, former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga set up a two-judge court that then upheld the magistrate’s conviction of the three accused persons.

NOT COMPETENT

As one of the two judges was from the ELC, the accused brought a further appeal in the Court of Appeal, arguing that the court was improperly constituted and its judgment was unlawful.

Agreeing with this argument, the Court of Appeal found that a judge of the ELC was not competent to sit in the ordinary High Court.

The effect of the judgment, which the Supreme Court has now confirmed, is that the judges in each of the three streams of the High Court cannot sit in any court other than the one to which they were appointed.

There is still pending for determination before the Court of Appeal a separate appeal against a judgment of the High Court in Malindi, which found that the provisions of the new Constitution authorising the ELC confer on this court a jurisdictional monopoly over land disputes and therefore ousts the authority of magistrates’ courts over this category of cases.

SPECIALISED JUDGES

The ELC and the ELRC are regarded as specialist courts and have fewer judges than the mainstream High Court.

While the Judiciary has made commendable efforts that have seen the establishment of High Court stations in all major towns around the country, the ELC and the ELRC are not always represented in these towns.

Because this interpretation bars ordinary High Court judges from hearing cases over which the ELC and ELRC have competence, litigants will now be forced to travel long distances in search of these specialised judges.

This interpretation also removes the flexibility that was previously possible, and which aided case management.

WORK OVERLOAD

The interpretation creates boundaries that judges cannot cross.

This means that they cannot share work, a situation which will see some judges overworked while others carry the lightest of loads.

Already, in parts of the country where land cases occur frequently, ELC judges are groaning because of overload but none of their colleagues from the other streams can assist them.

Also, while magistrates’ courts are designed to handle the bulk of cases that go to court, the finding that these have no jurisdiction in land disputes has thrown the administration of justice into disarray as magistrates are waiting for a resolution of the cases before court in order to know whether or not they can hear land cases.

RESOLVE MATTERS

Ultimately, the dispute regarding which court has what jurisdiction is arcane and feels like an indulgent house-keeping quarrel among lawyers.

The only problem is that the dispute has created bewildering hardships for litigants and caused monumental difficulties in planning.

The Chief Justice would do well to take charge and ensure this is resolved quickly.

The Judiciary will be forced into fresh planning over its ideal personnel requirements, as the effects of maintaining specialist courts alongside the High Court continue to clarify.