Our Constitution risks being rendered hollow by the Executive

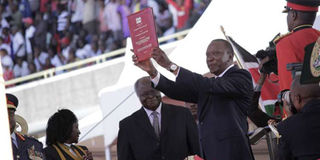

Newly-sworn-in President Uhuru Kenyatta (right) holds a copy of the Constitution handed to him by outgoing President Mwai Kibaki (centre) during his inauguration at Moi International Sports Centre Kasarani in Nairobi on April 9, 2013. PHOTO | EMMA NZIOKA |NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The lesson is that no matter how good a constitution, it is almost always at risk of being rendered hollow by Executive overreach.

- Our task is to be constantly vigilant and focus on public interest rather than increasing power for potential dictators.

The recent decision by the Supreme Court on the retirement age for judges is welcome. It included doses of common sense—which may not be so “common” as my former high school principal used to say—and it managed to maintain the right to an appeal for the applicants before a later uncompromised court.

Disappointing as the dissenting opinions were, the bigger issue was the hidden hand of the Executive, which revealed itself when the Government Printer delayed in publishing the vacancies for the judge’s positions clearly at the behest of someone with a lot of power who wanted former Judges Kalpana Rawal and Philip Tunoi to remain at the Supreme Court for reasons yet undeclared.

These antics of interference by the Executive in independent bodies and institutions should worry us, especially with our Constitution written in blood, sweat and tears, and whose major thrust was controlling the powerful, and creating institutions that would serve and protect ordinary people, rather than the powerful.

The impetus to control these institutions is never about public interest. It is always about accumulation of power in the hands of a few to enable patronage, impunity and authoritarianism. This is not the first time we have seen these sorts of attempts by the Jubilee regime: We have the apparent submission of the anti-corruption commission, which seemed to bend over backwards to do what the Executive wanted, whether it was hounding out unfavoured public officials or “clearing” favoured ones. There are also the crude attempts to hobble devolution by trying to control their spending from the Treasury and also delaying funds to the counties on flimsy excuses.

I have just finished reading the South African book We Have Now Begun our Descent by Justice Malala, an ANC stalwart from his teenage years, detailing how President Jacob Zuma has been trying to control or destroy independent constitutional institutions in order to avoid accountability for corruption and abuse of office, especially hinging on the renovations of his rural home at Nkandla that swallowed up about $20 million (Sh1.6 billion). The renovations were supposed to boost security at President Zuma’s rural home, but included a chicken run, a swimming pool and cattle kraal.

Justice Malala tells how he boasted to some prominent Nigerians in Lagos in 2004 that South Africa would never go the way of Africa because it was the country of Nelson Mandela and had “the world’s most admired constitution.” His Nigerian friends all laughed.

South Africa’s descent took some time because it was lucky to have Nelson Mandela as president, a man of unquestionable integrity and respect for the rule of law (not rule by law.) So much so that when he was summoned, as president, to give evidence in a minor court case about racism in South African rugby, he willingly went and turned the tables with his humility and dignity.

The ascent of Jacob Zuma has changed everything. He came into office with corruption clouds hanging over him, including the fact that tenderpreneur Schabir Shaik had been convicted of, and jailed for, bribing Zuma, who somehow escaped accountability. A bit like our Chickengate scandal where the bribe givers are in jail in the UK but the bribe-takers are still in office at the IEBC!

The process of institutionalising impunity started with the disbanding of the Scorpions investigative unit, by the ANC-controlled Parliament, as soon as Mr Zuma became the president of the party. This was the unit that had investigated Shaik and ensured he was brought to justice.

Today, the pressure is on the institution of the Public Protector and on the Protector herself Thuli Madonsela. Her reports on Nkandla have been devastating and recently the South African constitutional court declared that her reports are binding and not advisory as the Executive wanted. But as her terms ends in August there is little doubt that Zuma will do all he can to ensure that the next holder is more pliant and submissive.

The lesson here is that no matter how good a constitution, it is almost always at risk of being rendered hollow by Executive overreach. Our task is to be constantly vigilant and focus on public interest rather than increasing power for potential dictators.