Kenya is deficient in public diplomacy: So how do we expect to sell this country?

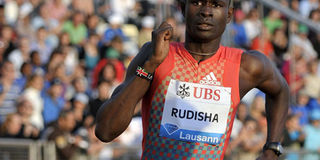

World 800m record holder David Rudisha during a past competition. One may argue rightly that athletes should pay tax ‘like everybody else’. But shouldn’t Kenyans be paying their athletes for making our country proud, often with only ‘raw’ talent? PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- One may argue rightly that athletes should pay tax ‘like everybody else’. But shouldn’t Kenyans be paying their athletes for making our country proud, often with only ‘raw’ talent?

- Criticism of the decision by the taxman to show gratitude to our athletes by taxing them should trigger a bigger question: what is the state of health of our public diplomacy?

- The so-called ‘New Public Diplomacy’, one in which nations use new media to mould international likeability, would call for the merging of information technology and communication in all its forms. Better still, why not elevate public diplomacy to a distinct directorate rather than placing it in the Siberia of foreign policy?

It is hard to argue on the side of those who want athletes taxed.

Even if you were the devil’s advocate, you would still struggle to hold up any really significant investment that this and past governments have made in sports.

Yet every time a Paul Tergat or Catherine Ndereba has stepped forward at an Olympics podium, Kenya has skimmed off succulent national PR.

One may argue rightly that athletes should pay tax ‘like everybody else’. But shouldn’t Kenyans be paying their athletes for making our country proud, often with only ‘raw’ talent?

Criticism of the decision by the taxman to show gratitude to our athletes by taxing them should trigger a bigger question: what is the state of health of our public diplomacy?

If winning hearts and minds in foreign lands remains one of the cogent definitions of public diplomacy, then ours is mostly comatose.

We don’t have a BBC, VOA, CCTV or Al Jazeera to carry the Kenyan message around the world, KBC having failed to click even at home.

We don’t have a Confucius Institute, British Council or American Peace Corps programme to showcase our diverse cultural heritage. Our websites have not graduated to web portals, so we cannot compete in cyber-space.

Indeed, we should be grateful for the airspace and column inches that flicker on the global media when our National Anthem is played in marathon circuits in cities such as London and Boston, or when Lupita Nyong’o becomes a film star.

If you doubt our ill use of the Internet visit, www.kenyanewsagency.go.ke, and compare it to, say, Xinhua News Agency’s www.xinhuanet.com. The less said about most digital platforms run by government agencies, the better!

MALAISE AT HOME

Perception and opinion practitioners have mined this to craft an image of a country hovering on the brink of state failure.

Yet, the public affairs division of Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade has not seen it fit to counter these negatives with inexpensive technology.

For instance, none of our embassies have press attachés. In fact, public diplomacy abroad is dead, from Canberra to Reykjavik.

Past administrations have outsourced communication with foreign audiences to international PR agencies, but it’s doubtful that this top-dollar approach would match posting communication-savvy diplomats to worry about our image abroad daily.

Constraints abroad reflect malaise at home. If you look at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ website, you will notice the curious duplication evident in Information and Communication Technology as a stand-alone unit and another one designated as Public Affairs and Communication.

It has been over a decade since the line between communication and technology blurred. Is it possible that our foreign affairs honchos are not familiar with this convergence?

The so-called ‘New Public Diplomacy’, one in which nations use new media to mould international likeability, would call for the merging of information technology and communication in all its forms. Better still, why not elevate public diplomacy to a distinct directorate rather than placing it in the Siberia of foreign policy?

If you are a watcher of information flow from the ministry to its many publics, you will notice that such an important national image and branding entity has no spokesperson — to link with local and foreign news media, for instance.

What muddles matters more is that the administration features well-regarded journalist Manoah Esipisu as Secretary of Communication, State House Spokesperson and Head of the Presidential Press Service.

Where does this leave the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology? And how does this link with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs?

In a nutshell, Kenya’s channelling of information abroad is dead, and some form of resuscitation is needed.

In the meantime, a way should be found to plug resource deficits rather than taxing the icons of Kenya’s international image recognition — athletes.