Lessons learnt from interviews for position of Chief Justice

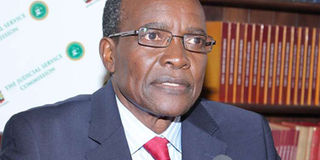

Justice David Maraga before the Judicial Service Commission for an interview for the position of Chief Justice on August 31, 2016. On September 22, 2016, the group nominated him for the job. PHOTO | DENNIS ONSONGO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The reforms that Kenya has undertaken in the Judiciary were towards ridding the institution of the improper influences exerted by interest groups.

- That the Judicial Service Commission can so easily substitute the improper preferences of those interest groups with the improper preferences of individual members of the commission means that the war towards judicial reforms has not been won.

As Kenya awaits the parliamentary process that will determine if Justice David Maraga is to be confirmed as the next chief justice of Kenya, it is useful to reflect on any lessons that have been learnt from the interview process that led to his nomination.

In a typical office interview, the candidates invited for interview would usually be unknown to the interviewers with whom they would get to meet as perfect strangers. In the circumstances, the basis of determining suitability for employment would be the resumes that the candidates would submit, the views of any referees and their performance at the interview.

Unlike the typical workplace interview, all the serious candidates that were interviewed for chief justice were already well known to many of the interviewers. As former university lecturers, Justices Jackton Ojwang, Aaron Ringera and Smokin Wanjala taught at least half of the members of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) who were now interviewing them. Five of the six candidates that made the initial shortlist were all serving judges and, therefore, close office colleagues of some members of the JSC. The fact that the JSC exercises a role in the discipline of judges also means that a number of candidates that came for interview had already had interactions with the JSC when exercising its disciplinary mandate. Even “outsiders” like Lawyer Nzamba Kitonga and Prof Makau Mutua were already well known to the interviewers, because they have large public profiles.

The JSC avers that when selecting the chief justice and other judges, it is committed to a merit-based process where bias will not be allowed any room. However, because bias is part of human nature, it is not unexpected that candidates who face interviews will have to endure whatever biases reside among the members of the JSC.

FALLIBLE PROCESS

The fact that Prof Mutua ended up ranking third in the interviews, even though the JSC had initially blackballed him, is evidence that its process was fallible.

In workplace interviews, the range of bias influence is significantly limited because of the relatively limited prior interaction that the interviewers would have had with applicants. In the case of the JSC, all the interviewers have had significant amounts of prior interaction with the candidates. Further, some of the candidates hold well-publicised opinions which may be at variance with those held by individual JSC members.

On this point, the tendency of the JSC to dwell on political or social issues around which there is some controversy suggests that they saw themselves as a moral police in society and that part of their job was to sieve out persons who hold views that the mainstream of society disapproves of. As an example, a member of the JSC asked Prof Mutua what religion he belonged to. Here, the JSC was introducing a religious test for determining suitability for public office, even though such a test is patently illegal.

As a further example, the question of whether a candidate would be able to “work with the president”, because of his political views, was a nebulous political test. Was this a loyalty test, similar to the loyalty tests during the Kanu era? What was its pass mark and how would this be evidenced? The JSC commissioners, two of whom had been appointed because of their presumed willingness to do the bidding of the political establishment, were saying that any political views contrary to their own were wrong, and a source of disqualification. These considerations would have been relevant if the JSC was hiring the CEO of the Jubilee party rather than the chief justice for Kenya.

CANDIDATES’ PERFORMANCE

The JSC went to the unusual length of releasing information regarding the performance of the top candidates in the interviews. Because the interviews were aired on television, providing opportunity for the public to reach its own conclusions about the candidates, there has been a debate about the scoring, with suggestions that factors beyond the observable performance of the candidates were taken into account in the selection process.

Because even well-meaning people harbour biases that they may not even be aware of, or are unable to overcome, it is clear that JSC members approached the interviews with individual and collective biases and that the biases played a role in the selection process. While the extent and effect of these biases is not clear, its existence cannot be denied. Overall, the circumstances present a picture where the public can reach well-founded conclusions that some decisions by the JSC were faulty.

The explanations that the JSC has offered about its selection process will remain unconvincing unless the body can show that it had a pre-established criterion for ranking candidates and how the criterion was applied in practice. Even then, there will still be outstanding questions because all rational people recognise that it is unlikely that the JSC members suddenly blocked off what they already knew about the candidates and scored them solely on the basis of their performance on the day.

The reforms that the country has undertaken in the Judiciary were towards ridding the institution of the improper influences exerted by interest groups. The fact that JSC can so easily substitute the improper preferences of those interest groups with the improper preferences of individual JSC members means that the war towards judicial reforms is not won.

It would not be unreasonable that the JSC should consider subjecting its future interview processes to external moderation. The form and nature of such moderation can be discussed but the assumption that the JSC always knows what is best for the country is unfounded.