Politicians peddle lies about ethnic unity

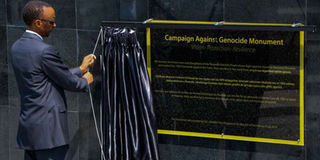

Rwanda's President Paul Kagame unveils the plaque for the Campaign Against Genocide Monument at Parliament on Liberation Day on July 4, 2014. PHOTO | CYRIL NDEGEYA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

It is not just about groups channelling their grievances in an effective way, but also the manner in which the State addresses such grievances without giving an opportunity for them to escalate.

It is a common trend in Kenya to see people from different ethnic groups, who look like football fans, singing common traditional songs whenever we get close to the electioneering season. In this way, they express their anger over unfulfilled political promises or seek help and support from the government.

This is the season when many incumbent and aspiring political leaders seek fortune by using the ethnic template to mobilise the public. But the African political mobilisation distracts people from their real economic aspirations. It was Prof Ali Mazrui, who once said that the conflicts between whites and blacks in history were about who owns what, but black-versus-black conflicts are usually about who is who.

TO VOTE

For instance, one will find politicians talking of the unity of their people to vote, but not for development. They preach for bloc voting because they speak one language. Politicians forget that language on its own can never be a unifying factor; at best it only creates temporary solidarities that are cobbled together to ward off a perceived threat. We have seen such examples in Somalia and Rwanda, and Kenya’s tribal coalitions.

Politicians in Africa preach the gospel of ethnic unity. Indeed, unity forged on such a dubious platform as tribe is, as Chinua Achebe suggested in The Trouble with Nigeria, a kind of unity that looks and smells like a conspiracy against a bigger ideal of fashioning a nation out of the shell that is a nation-state.

I have always been apprehensive of individuals who call for Meru unity, knowing that such pleas may lead the people into the trap of ethnic enclaves that may eventually implode. We have nine sub-tribes in the larger Meru: Imenti, Igembe, Tigania, Chuka, Tharaka, Mwibi, Muthambi, Igoji and Mitine. The unity of Meru sub-tribes is called upon by politicians for voting only. It is not meant for economic development.

For instance, Tharaka is the only sub-tribe of Meru that has never seen a tarmac road. The Tharaka have to travel long distances to get services. This becomes worse during the rainy season. Last week, the Tharaka people camped at Kathwana, the headquarters of Tharaka Nithi County, protesting that their land was being taken over by another sub-tribe.

LONG-RUNNING GRIEVANCES

No one can deny that different groups and regions in this country have long-running grievances against the central government. The coastal region, the former Northern Frontier District, Nyanza and western regions have, no doubt, been done in badly by successive regimes. And they have reason to complain and seek redress.

Retreating into ethnic cocoons as a basis of lodging such grievances is both ineffective and dangerous. It makes the hard task of nation formation harder, and it creates a spiral web of ethnic manipulation, rising expectations and rising frustrations, all leading to a political dead end.

Such strategies create ambiguities of belonging, where the tribe matters more than the nation.

It is not just about groups channelling their grievances in an effective way, but also the manner in which the State addresses such grievances without giving an opportunity for them to escalate. Ignoring such grievances, as Rwanda’s President Juvenal Habyarimana did prior to 1994, is one option. The other is how the United States dealt with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, making concessions and anchoring such in the Constitution to ensure greater accommodation of genuine concerns from all quarters within the country. For our leaders, the choices are clear.

Jonah Kindiki is a lecturer of international education and policy analysis and dean of the school of education at Moi University.