Security of all Kenyans lies in being true to constitution

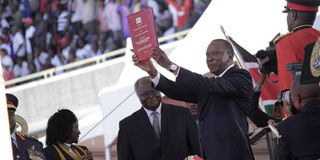

Newly-sworn-in President Uhuru Kenyatta (right) holds a copy of the Constitution after outgoing President Mwai Kibaki (centre) had handed to him during the former's inauguration at Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi on April 9, 2013. PHOTO | EMMA NZIOKA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The security of every Kenyan will only be guaranteed by implementing the Constitution, and serious efforts to promote diversity and nationhood.

- Any other way will only breed crisis and tension.

I find it difficult to avoid issues around the legacy of colonialism, apartheid and racism in southern Africa, which is where I am as I write this. The issues are pervasive, even in unexpected ways in countries like Swaziland. An absolute monarchy, Swaziland’s economy and political life has been declining since the end of apartheid in South Africa.

At the height of apartheid, and especially when sanctions were imposed against South Africa, many companies shifted to Swaziland. But because Swaziland maintained relations with its giant neighbour, the companies could still service the much larger South African market. In fact, Swaziland was the location of choice for sanctions-busting, as goods meant for South Africa, and from South Africa, were transferred from Swaziland.

Today, almost 70 per cent of the Swaziland population lives below the poverty line even though the per capita income is about $2,500 (Sh259,000), illustrating the gigantic levels of inequality; HIV/Aids affects 26 percent of the population; corruption and kleptocracy are on the rise; and about half the population is under 25 years old.

Clearly, Swaziland needs serious and creative thinking on how to expand its economy, and reduce inequality, if it is to avoid imploding. It has a small market with a population of just over 1 million people, which makes it necessary to make tough but pro-people decisions to overcome this particular legacy of apartheid.

AN ORGANISATION

Coincidentally, in Swaziland, I came across an interesting article in the current issue of Foreign Policy about an organisation in South Africa called AfriForum that advocates the rights of Afrikaners in the country. This includes fighting against affirmative action for black South Africans, insisting on the use of the Afrikaans language in schools and universities, defending the statues and icons of Afrikaner history including those who perpetuated apartheid, and trying to maintain a favoured position for Afrikaners. It has been a project to “rebrand the Afrikaner identity from the oppressors to the oppressed”.

This appropriation of the victim narrative is ironical given that white South Africans have – as a group – gotten more prosperous since the end of apartheid!

Now, appropriating victimhood by those in power or have benefited from proximity to power is a tried and tested tactic at personal and community levels. We have seen how fast the powerful run to their villages to clothe themselves in their communities when they are accused of corruption or violent crimes! And those especially good at it then run for higher and higher office as the “protector” of their people!

But appropriating the narrative by groups or communities can be quite dangerous, beyond the absurdity of it all. After the First World War started – and lost – by the Germans, and after a peace deal that the Germans considered too harsh (especially the War Guilt clause), a narrative of victimhood arose in the country. Adolf Hitler’s rise to power resulted from combining that sense of victimhood with a narrative of German superiority and “specialness” that attracted millions. Hitler came to power in a blaze of nationalism, reinstated the German war machine and started the Second World War. Modern-day genocide, in the form of the Holocaust, resulted and a whole genre of international criminal law emerged after the Germans were conquered.

SIMILAR TACTICS

We have seen the use of similar tactics in Kenya. In 1969, for example, the central Kenya community was taken through oath-taking ceremonies where the idea of victimhood was emphasised in an oath to keep power in the community at all costs. Were it not for some bold church leaders who challenged President Jomo Kenyatta, and thus stopped the ceremonies, Kenya’s history would be very different today.

Sadly, we do not seem to have learnt since. Anyone following the messaging on vernacular radio stations and on social media around the recent mass voter registration exercise – including songs and short clips – should be worried. While not as explicit, the narrative has been consistent.

This should worry us all. The security of every Kenyan will only be guaranteed by implementing the Constitution, and serious efforts to promote diversity and nationhood. Any other way will only breed crisis and tension.