Uhuru's legacy linked to securing Constitution's promise

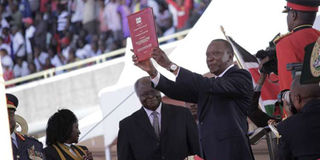

Newly-sworn-in President Uhuru Kenyatta (right) holds a copy of the Constitution after outgoing President Mwai Kibaki (centre) had handed to him during the former's inauguration at Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi on April 9, 2013. PHOTO | EMMA NZIOKA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

Kenya’s dream of joining the league of the world’s middle-income economies is closely tied to securing the promises of the Constitution.

- The body of fundamental principles is poised to shape the legacy of President Uhuru Kenyatta after next year’s General Election.

It is World Bank Country Director Johannes Zutt who rightly declared that “Kenya is in the midst of a quiet revolution”.

He was commenting on the impact of Kenya’s new Constitution, adopted six years ago on August 27, 2010, which launched the country on the path of democratic values of good governance, rule of law and social inclusion in development.

Kenya’s dream of joining the league of the world’s middle-income economies is closely tied to securing the promises of the Constitution. And the supreme law is poised to shape the legacy of President Uhuru Kenyatta after next year’s General Election.

In his ambition to “make Kenya great” among world nations, Kenyatta will have to hue his legacy against two extremes. On the one end, he has to dismantle the colonial legacy that divided the country into high-potential and low-potential areas. Indeed, the failure of the post-colonial state to reverse this historical injustice stoked a slew of grievances that segments of the political class whipped to ignite the 2008 post-election violence.

On the other extreme, Kenyatta has to build his legacy in a 21st century world where the dominant capitalist system on which the new Constitution is embedded is going through one of its worst crises. Kenya needs to be strategic at three levels.

At the local level, the government has to implement the Constitution to bring the poorest of Kenyan regions from the margins and into the fold to share in the making and enjoying of the wealth of the nation.

On August 25, 2016, I joined a delegation of the UN and its partners that toured the market town of Moyale on the border of Ethiopia and Kenya’s Marsabit County, one of the poorest counties in the country with a poverty rate of 83.2 per cent (way above the national average of 47.2 per cent).

In myriad ways, Moyale reveals the two faces of the new Constitution. It proves that the Constitution’s “county magic” is manifestly the sharpest tool of rolling back the colonial legacy of underdevelopment.

COUNTY GOVERNMENTS

Since 2013, the Jubilee Government has implemented 47 county governments, ushering in Kenya’s homegrown “Marshall Plan”. From $210 million allocated in 2013, funds devolved to the counties have increased to $280 million in 2016. The lion’s share of this money is going to marginal counties.

The last time I visited the town in 2000, as part of the Kenya Human Right Commission’s fact-finding mission in the wake of violent clashes on the Kenyan side of the town in early 1999, Moyale was a conflict-prone, dusty remote town.

In 2016, this has changed. The 240-kilometre Merille-Marsabit-Moyale road cuts through the town, linking Kenya to 90 million people in the Ethiopian economy. Moyale has a referral hospital, the largest in the region, serving Kenyans as well as Ethiopians. In June, Marsabit County had its first-ever caesarean section!

But a winner-takes-all logic in the Constitution can be a recipe for perpetual instability. Fear of exclusion from decision-making has led to increased cyclical conflict in volatile areas such as Moyale with a history of stiff competition over scarce resources including land, pasture and water in the context of drought, poverty and stress related to climate change.

In the March, 2013 General Election, Moyale was the epicentre of a deadly inter-clan armed conflict between the Borana and the Gabra. Here, a coalition of the ethnic minorities (Gabra, Rendille and Burji) won all the seats in the county government, leaving the majority Borana community feeling politically marginalised and under-represented in the various county structures and sharing of devolved cash. Schools were burned down and closed, businesses shut down and transport suspended, spiking food prices.

Peace has been restored and houses and communities have been rebuilt. But the lesson is clear: building trust, and improving conditions for shared development are key to peace and sustainable development.

At the conceptual level, Kenya has to balance between the imperatives of capitalism and democracy in order to create a shared wealth and prosperity. In a sense, Kenya’s 2010 Constitution signifies the inherent tension between markets and democratic politics.

THROUGH VOTE

While capitalism allocates resources through markets, democracy allocates power through the vote. In earlier decades, democratic states managed to tame capitalism and ensure a degree of shared growth by establishing protective labour laws, restrictive financial regulations, and expanded welfare systems.

But the politics of neo-liberalisation under Reagan, Thatcher and Kohl in the 1980s enthroned a globalised, deregulated capitalism, unconstrained by national borders and setting the rules that democratic governments and weakened states must follow.

The sway of capital has exacerbated poverty and provoked backlash. This has pushed inequality to perilous levels, creating a 9 per cent poor and 1 per cent wealthy. In 2012 alone, the top 100 billionaires in the world added $240 billion to their coffers. Experts calculate that this is enough to end world poverty overnight.

In this context, Kenyatta’s decision last week to take his most courageous step to sign into law the Banking Act capping interest rates is revolutionary. Kenyatta has reversed Kenya’s earlier move in July 1991 to eliminate its interest-rate limits as part of the ruinous IMF induced Structural Adjustment Programmes. He has also made good on his earlier promise to bring down interest rates.

Finally, Kenya has to take a hard relook at the strategic partnerships at the regional and international level. Back to Moyale, one of these partnerships is Cross-Border Integrated Programme for Sustainable Peace and Socio-economic transformation – Marsabit County and Ethiopia’s Borana Zone, witnessed by President Kenyatta and the Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn of Ethiopia on December 8, 2015. The framework has huge potential for increasing opportunities for trade, investment and tourism in one of Kenya’s poorest areas — which Kenyatta sees as “the future Dubai of the Horn of Africa”. It involves a $200m trade agreement aimed at ensuring peace and increasing security along their conflict prone common border regions. The initiative is supported by the UN, which started with a funding of Sh20bn to support peace building and conflict management initiatives.

The new Constitution positions Kenya at the forefront of the global efforts to reshape and re-engineer capitalism to create a new version of a more humane and inclusive economy. But ensuring a credible, free and fair election devoid of violence in 2017 will further consolidate Kenya’s democracy.

Professor Peter Kagwanja is the chief executive of the Africa Policy Institute.