Despite belief, voting in Kenyan elections is not merely defined by ethnicity

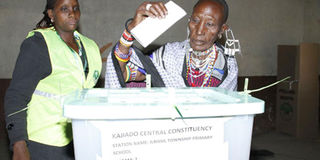

A voter casts her ballot at Ilbissil Township Primary School in the Kajiado parliamentary by-election on March 16, 2015. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- A high level of political scepticism about the motivations of others encourages many to vote ethnically because they believe that this is how the majority of Kenyans will behave.

- Leaders cannot simply rely on votes from their communities, or buy them, but have to persuade their co-ethnics to vote for them.

- Any move against an ethnic spokesman can easily be reinterpreted as an attack on an entire community, as marginalisation of the former is often feared to herald the marginalisation of the latter.

Clear ethnic voting patterns have led some to suggest that Kenya’s elections are a little more than an “ethnic census” – with polls becoming a mere headcount of ethnic groups and alliances.

This is often explained in the academic literature through reference to a top-down instrumentalisation of ethnic identities by politicians who seek to gain or maintain power. Or, alternatively, by the idea of patronage politics where citizens vote for ethnic spokesmen in exchange for individual or collective goods.

However, the idea of a census and associated explanations are too simplistic.

First, since the level of cultural or linguistic similarity cannot explain when a group of people comes to be considered as an ethnic group or not, the salience of ethnic identities always demands an explanation.

Second, the fact that ethnic identities can expand and contract depending on the context, complicates any notion of ethnic arithmetic. For example, of whether the Somali, Kalenjin, Luhya or Mijikenda consider themselves as a single community in the political arena, or whether different leaders manage to mobilise support among various sub-groups or clans.

Third, while national elections are characterised by clear ethnic voting patterns, some ethnic groups (such as the Kikuyu and Luo) have historically been more united than others (such as the Luhya and Somali). The implication, once again, is that the salience of ethnic identities is not an explanation, but instead, always needs to be explained.

NOT ALWAYS

Fourth, while patronage and direct assistance are clearly important, those who spend the most do not always win. Instead, other factors – such as people’s evaluations of an individual’s development performance or oratory skills, or their religion, class, and gender – are clearly important.

So how can one best explain ethnic voting patterns?

In my opinion, the answer lies in a combination of what Susanne Mueller has called “exclusionary ethnicity” or who will “not get power and control the state’s resources”; and what I have called, “speculative loyalty”, or a calculation of the potential advantages of electing community spokesmen.

These two logics – of keeping particular ‘others’ out and of voting for “one of your own” – is shaped both by history and by popular perceptions of how others will behave.

With regards to the former, a sense that some communities have been marginalised, renders it rationale to support “one of your own” as a way to address historical injustices. At the same time, a sense that some have enjoyed disproportionate benefits from having “one of their own” in power, means that members of such communities – even if they do not feel that they have personally benefited – may fear the rise to power of an ethnic ‘other’ lest resources be redirected to others.

This ensures that many issues and policies gain an ethnic logic, as a focus on trickle-down growth, for example, is often seen to favour those communities whose areas are already relatively developed.

In turn, while many Kenyans would prefer politics to be non-ethnic, their behaviour is influenced by how they believe others will behave. In this vein, and in a survey conducted before the 2007 election, Michael Bratton and Mwangi Kimenyi found “that Kenyans do not easily trust co-nationals who hail from ethnic groups other than their own” and that “they worry that their co-nationals are prone to organise politically along exclusive ethnic lines and to govern in discriminatory fashion”.

FURTHER ENTRENCHED

Unfortunately, such perceptions only seem to have become further entrenched in the last decade – as Kenyans experienced the post-election violence of 2007-2008 – and as politics became increasingly polarised in the post-2010 context.

This understanding of ethnic voting has at least three implications. First, it means that a high level of political scepticism about the motivations of others encourages many to vote ethnically because they believe that this is how the majority of Kenyans will behave.

Second, it means that leaders cannot simply rely on votes from their communities, or buy them, but have to persuade their co-ethnics to vote for them. In short, politicians need to present themselves as strong representatives of community.

Finally, it means that any move against an ethnic spokesman can easily be reinterpreted as an attack on an entire community, as marginalisation of the former is often feared to herald the marginalisation of the latter.

Gabrielle Lynch is associate professor of comparative politics, University of Warwick, the United Kingdom and columnist, Saturday Nation.

@GabrielleLynch6