We have a ‘fake news’ problem but not one you’re thinking of

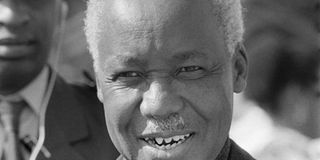

Tanzania's President Julius Nyerere . PHOTO | AFP | EPA

What you need to know:

I am not sure why we are imprisoned by other people’s view of the world and buzzwords, and why we do not amplify the voices of our own.

It could be that part of it has to do with the messenger.

We just do not privilege the voices of our own heroes and villains, because we do not do so to our histories and stories to begin with.

With the 2016 US presidential election campaigns and Donald Trump’s victory, the idea of “fake news” has taken root. Today, “fake news” is all the rage. I have seen serious attempts by African scholars to trace the history of “fake news” going back about 40 years in Kenya, and even further to 70 years earlier in apartheid South Africa. So this story will be with us for a while.

Related to that, is “post-truth”. Our intellectuals are busy dissecting the “post-truth” world ushered in by Trump. After the Britons voted to leave the European Union last year, you could not open a serious African newspaper without being assaulted by articles on Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, or whatever other land, in a “post-Brexit” world. African central bankers took to the newspapers to pen articles on how that world would look.

In 2013, United States Assistant Secretary of State Johnnie Carson seemed to suggest that it would be a mistake to elect then-candidate Uhuru Kenyatta and his running, Mr William Ruto, who had been indicted by the International Criminal Court in connection with post-election violence in 2007-2008.

He said “choices have consequences”. Between 2013 and late 2015, “choices have consequences” became the most flogged expression in Kenyan political punditry. And so, back to the fad of the day, if "fake news" has been around for so long, why did it take the American election for us to see it?

REAL DIVIDE

This whole thing demonstrates dramatically the real divide of world power. There is a global divide in wealth, military power, but the biggest one is the formation of ideas or concepts, what some people call “ideation”.

The concepts we spend our intellectual resources on, the way we frame the questions and clichés of the day, the myths we dwell on, the realties that we invest our time defending or disputing, all tend to be shaped, especially by the US and the UK.

And many times, even critics, don’t realise it. When US President George Bush and his hawks did his “war on terror”, and invoked James P. Wade’s “shock and awe” doctrine in the Iraq invasion of 2003, he set off a furious wave of criticism and pushback.

Yet, of the hundreds of thousands of articles and books that slammed the “war on terror”, none of them produced an alternative language. They all really were stuck with the “war on terror”, and we still live with it today.

The problem is particularly acute in Africa. Earlier leaders like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, and Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta had better luck. When you read Oginga Odinga’s autobiography Not Yet Uhuru, you can expect that it will be attributed to Jomo Kenyatta.

When one sees “committing class suicide”, anyone interested in the political economy of Africa will immediately conjure up images of the Guinea-Bissauan revolutionary leader and intellectual Amilcar Cabral.

NELSON MANDELA

South African statesman Nelson Mandela also bequeathed us more T-shirt and Twitter slogans than any other.

Over the last 20 or so years, however, it was former South African President Thabo Mbeki, who was most successful in crafting an idea that gained traction as a philosophy, with his “African Renaissance” . Of course, Mbeki himself didn’t come up with the idea. We owe it to Senegalese thinker Cheikh Anta Diop, who first articulated it in the late 1940s.

Mbeki retooled it, and soon we had African Renaissance institutes, and monuments, popping up in Africa.

I am not sure why we are imprisoned by other people’s view of the world and buzzwords, and why we don’t amplify the voices of our own.

It could be that part of it has to do with the messenger. Someone as charismatic as former US President Barack Obama, had a better chance of getting his “yes we can” to be a global sound bite.

I think, even when he is as colourful as he can be, the framing of Africa or the world from Zimbabwe’s 93-year-old strongman Robert Mugabe wouldn’t be very appealing.

Yet, even that isn’t sufficient explanation. Even villains, as we know, can capture the imagination and leave us with enduring ideas.

It might come down to the fact that we just don’t privilege the voices of our own heroes and villains, because we don’t do so to our histories and stories to begin with.

There are smarter Africans out there who can tell us why we don’t.

Charles Onyango-Obbo is publisher, Africa data visualiser Africapedia.com and explainer site Roguechiefs.com.

Twitter: @cobbo3