Africa needs more, not fewer, governance prizes

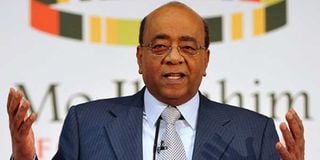

Mo Ibrahim, founder of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, speaks at the launch of the 2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) and the announcement of the 2013 Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership in London on October 14, 2013. AFP PHOTO | CARL COURT

What you need to know:

- Much of the debate has focused on the relevance of rewarding presidents with funds they probably do not need.

- Africa could benefit from a new generation of prizes that celebrate, reward and inspire ministers, governors and mayors.

- Recognising young leaders who demonstrate integrity in public leaders would play an important role in creating a culture of excellence.

- It is hard for leaders to deviate from the social norms from which they have emerged.

The 2014 Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership has been awarded to the former President of Namibia, Hifikepunye Pohamba, for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia's consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

In the eight years since it was launched, the prize has been awarded only four times because of the lack of suitable candidates. A Washington Post blog has called the irregular award “something really quite disheartening”.

The prize is given to a democratically elected former head of state or government who left office in the previous three years. The individual must have served his or her constitutionally mandated term and demonstrated exceptional leadership.

The conditions are as stringent as the value of the prize is large. The winner gets $5 million over five years and $200,000 after that for life. This makes it the largest prize in the world.

Much of the debate has focused on the relevance of rewarding presidents with funds they probably do not need. Others question the criteria used for selecting the winners and argue that judgment on leadership performance should be a national matter.

These arguments, while valid, miss the critical role that prizes perform in benchmarking excellence. The size of the prize is an indication of the premium placed on good leadership. If good leadership was so abundant in Africa such a prize would possibly not be needed.

The prize and the media attention it generates inspires leaders and their followers to think about the value of excellence in public service. The existence of a benchmark for governance makes leaders reflect on their contributions irrespective of whether they will win the prize or not.

Unlike other prizes where winners are based on public expectations, the decision is based an elaborate research effort that uses a wide range of metrics to recommend candidates to the selection committee. One can disagree with the criteria but cannot question the commitment to rigorous review.

It is true that some countries are more difficult to govern than others. This is not a reason to question the relevance of the prize. It is, in fact, an argument for more prizes, not fewer. There are many other African entrepreneurs who could help to broaden the base for excellence in public service by supporting other prizes.

For example, Africa could benefit from a new generation of prizes that celebrate, reward and inspire ministers, governors and mayors. In addition, there are many government officials, civil society leaders and entrepreneurs who have made outstanding contributions to improving excellence in public leadership.

Many of the habits that enhance or undermine public leadership are formed early in the lives of public leaders. Recognising young leaders who demonstrate integrity in public leaders would play an important role in creating a culture of excellence. Such prizes would be reinforce the pioneering support that is currently being provided by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

FORCE LEADERS TO LISTEN

The Mo Ibrahim Prize is also controversial because it strikes at the heart of Africa’s culture of political patronage that feeds the hydra of corruption. Most African leaders are elected by appealing to ethnic alliances.

The prize is about transparency in governance, not about expertise in backroom deals. It is about the values of excellence that should promoted across all aspects of Africa’s political, economic and social life.

Good governance is not a single act. It is a cultural expression that is acquired through long periods of political education. Rewarding leaders who have demonstrated a clear sense of purpose and effectiveness is critical to cultural learning.

When reviewing Africa’s governance, leaders get disproportionate attention compared to followers. Democracy is about the people, not just the leaders. Recognizing followers who have demonstrated outstanding courage to follow the rule of law is as important as honouring leaders. In most cases, leaders are expressions on the society they operate in. Corrupt cultures beget corrupt leaders.

It is hard for leaders to deviate from the social norms from which they have emerged. Rewarding and inspiring communities that stand for the values of excellence is as important as rewarding leaders. Such recognition would help strengthen the democratic role of citizens. Such empowerment of followers would also force leaders to listen more to the wishes of their followers.

Finally, creating leadership schools in African universities should be given priority. At the very least, such schools could offer short courses aimed at equipping new legislators with rudimentary knowledge on the ethics of public services.

Mo Ibrahim has put a price tag on the quality of Africa’s public leadership. The intensity of the debate shows that one prize is not enough. The time has come for Africans entrepreneurs to create more prizes to recognise, celebrate and inspire excellence in public leadership. That would be a more appropriate response to Mo Ibrahim’s challenge.

Professor Juma is Faculty Chair of the Mason Fellows Program at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government, where he specialises in technology and development. Twitter @calestous