Committees without commitment: How not to draft a code of ethics

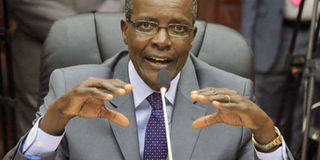

Chief Justice nominee David Maraga being vetted by the Justice and Legal Affairs Committee on October 13, 2016. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- After 2010, a new code of conduct was urgent. A committee was constituted with the tough task of drafting a new code of conduct.

- David Maraga will have the pressing challenge of outlining a system to deal with behaviour and practices contradicting the tenets of the code.

Today's governance is full of committees. Everything must be decided under that popular banner, "we decided", which means democracy has been taken to its last social consequences.

"We decided" is actually quite essential when it comes to collegial decision-making.

It entails putting minds together to reach a more perfect and balanced decision; a decision that's not blurred by just one individual's prejudices, ignorance, cultural views or simply selfish interests.

But "we decided" cannot be transposed to the execution level. Execution is quite personal “It is my responsibility”, for execution needs a responsible person behind, the one who sticks his neck out, the one who will be blamed or praised.

One of the greatest misunderstandings of committee-work nowadays is that "we decided" is mistranslated to "we did".

This “we do” is a type of mob mentality at the execution level. It can turn out to be a blatant scape goat for responsibility.

This is actually how we resolve issues to do with responsibility nowadays, hiding behind that false “we all did it”.

It happens in our streets with mob justice. When the mob kills the thief no one goes to jail…for we all did it.

"We all are guilty" is the perfect remedy for my conscience. We hide our personal responsibility behind this abstract word “committee” that makes us all feel comfortable, together.

Our MCAs have become perhaps the most dramatic form of modern mob justice.

Nowadays, there is a committee for everything and for everyone. We are together, tuko pamoja.

This togetherness works very well for good things, good causes, even good politics.

But it can also backfire, and when it does, responsibility is watered down, because everyone’s fault is nobody’s responsibility. I saw this happen at a recent wedding committee.

THE IDEAL JUDICIARY

A few days ago, I was asked to write a chapter for an upcoming book.

I chose the topic of judicial independence and accountability in light of the judiciary code of conduct and ethics of Kenya, 2016.

In 2010, after passing the constitution, it became clear that the new judiciary needed to up the ethics game.

A strong judiciary is the pillar and foundation of the rule of law in a democratic system.

A strong judiciary needs intellectual, structural and financial independence, coupled with professionalism.

The judiciary is the lubricant that facilitates and harmonizes institutional and personal relationships in a society.

When the judiciary weakens other institutions collapse, and this causes a domino effect that ultimately undermines the rule of law in its entirety, and eventually destroys democracy.

It is not sufficient to be independent; it is also necessary to appear to be independent. It is precisely this difficult interplay between reality and perception that makes judicial codes of ethics a precondition for legitimacy.

A working judiciary demands certain key conditions. For example, judges must perform their duties within an appropriate physical space, within a good structure and a comfortable budget.

However, judges also require special professional training, a deep knowledge of the law, of the human being, and of society.

Judges must be true thinkers, fair, impartial and independent-minded persons.

The best judge is not necessarily the most efficient, the one who decides most cases in less time, nor the most popular one.

Judges are neither soccer coaches nor dream team managers. Their work is not a popularity contest.

According to the Israeli Judge Aharon Barak, judges should never express their own personal views, but rather the fundamental beliefs of the nation, no matter how popular or unpopular.

After 2010, a new code of conduct was urgent. A committee was constituted with the tough task of drafting a new code of conduct.

In the end, and with the help of a number of experts, several very similar drafts were produced.

The proposed structure had five parts: Part I on the interpretation of terms. Part II applicable to judges.

HUGE FAILURE

Part III applicable to judicial officers. Part IV regulating the conduct of judicial staff, and Part V dealt with enforcement, oversight and implementation.

The code promotes the values of prudence, justice, equity and integrity in the judicial profession for the benefit of the whole society and the effective implementation of the rule of law and other democratic values.

The code also borrows heavily from the international Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct that have guided the drafting of most modern judiciary codes of conduct.

The Bangalore Principles established six core values to guide judicial conduct: independence, impartiality, integrity, propriety, equality, and competence and diligence.

These principles try to protect the judiciary from any pressure or conduct that might undermine judicial independence, integrity and impartiality.

This new code was set to replace the 2003 Judicial Service Code of Conduct and Ethics under the Public Officer Ethics Act.

The code in addition would also apply the other laws that relate to codes of conduct and ethics.

The code would also serve as the specific code for the judiciary with respect to the provisions of the Public Officer Ethics Act, the Leadership and Integrity Act and the Public Service (Values and Principles) Act.

Then came the most difficult part. The politics of decision. Should there be one code for judges, magistrates and judicial staff? Or should there be three different codes? Should the code be passed by Parliament or be issued by the Chief Justice?

In the end, it was decided that the code would be signed by the Chief Justice, pursuant to section 47 of the Judicial Service Act. Willy Mutunga signed it just before he retired.

The signed version was quite faithful to the original proposed drafts, but it had a major omission. The implementation and enforcement part had been removed.

This omission castrates any hope of immediate implementation.

The advisory ethics board and the clearly defined disciplinary procedures were done away with.

This was a sad and huge pitfall. It left the code barren and sterile.

MARAGA'S CHALLENGE

This move disregarded recommendations that go as far back as 1998, when the Kwach Committee declared that corruption could only be brought to an end by having a code of ethics that ‘will outline the expected and prohibited forms of conduct as well as attendant penalties for transgressions…’

The 2008 Kihara Kariuki Committee of the Judiciary also considered the outlining of clear consequences in case of violation as an important way to ending unethical conduct in the Judiciary.

The code’s failure to provide clear sanctions for breach has made this new code a beautiful and ineffective instrument.

This situation could be reversed by the Judicial Service Commission and the Chief Justice, who are empowered to review the code.

David Maraga will have the pressing challenge of outlining a system to deal with behaviour and practices contradicting the tenets of the code.

Until this legal mischief is redressed the code will be largely useless.

It will actually jeopardise the purposes for which it was intended… and the committee will go down in history as a committee without commitment.

Dr Franceschi is the dean of Strathmore Law School. [email protected]; Twitter: @lgfranceschi