African elites plunder their countries at public’s expense

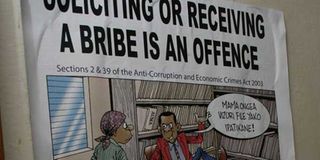

An anti-corruption poster in a government office. FILE PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- In Kenya, theft of public funds is covered up through businesses that appear legitimate.

- Such businesses do not just impact the owners, but their many suppliers and employees.

Does the raging political unrest in Togo have anything to with the fact that President Faure Gnassingbe entirely controls and benefits from the sale of phosphate, the country’s main mineral?

According to a new investigative report on how African oligarchs are looting the continent’s wealth at the expense of their own people, the Togolese president and his family have for decades been selling phosphate to “privileged clients” at below market rates and pocketing the money using offshore accounts.

The Plunder Route to Panama: How Oligarchs Steal from Their Countries, an investigation by the African Investigative Publishing Collective in partnership with Africa Uncensored and ZAM, examines the role African political leaders – in collusion with foreign interests – have played in undermining economic development and exacerbating poverty on the continent through the blatant theft of their countries’ natural and mineral resources.

OFF-SHORE ACCOUNTS

The investigation found that in Democratic Republic of the Congo – the world’s most mineral-rich country – President Joseph Kabila and his twin sister Jaynet have been stashing away millions of dollars in offshore accounts created specifically to receive the proceeds of illicit wealth stolen from their poverty-stricken country.

Some of these ill-gotten riches were obtained by extracting “taxes” from mining companies that never made it to the state treasury.

In many cases, politicians deliberately collude with foreign companies to deny revenue to state coffers.

For instance, a Canadian mining company was told that instead of paying the due tax of $60 million, it could get away with paying one-tenth of this amount to the government if it handed over $4 million to the tax director.

When the company refused to do so, its mine was seized and sold to an Israeli tycoon, who had fewer qualms about entering into such arrangements.

In South Africa, “state capture” by the Gupta family has exposed corruption and cronyism in Jacob Zuma’s government. Zuma and the Gupta family’s so-called “Zupta Empire”, consisting of shady contracts, siphoning of tax revenue and other dubious activities, highlights the fact that corruption can thrive even in a country with an independent judiciary, parliamentary oversight and press freedom as long as the top leadership benefits.

LOOTING

The report does not spare Rwanda and Botswana either, which have been hailed as models of good governance, though the looting there has not been as blatant as that in oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, for example, where the president and his son have been siphoning millions of dollars to France and other places.

(In a landmark ruling, the president’s son, Teodorin Obiang, was recently handed a three-year suspended sentence for embezzlement by a French court.)

I wish the authors had done a more comprehensive analysis of the seven countries they covered so for the reader to get a better perspective of the context in which this plunder occurs.

In many instances, anecdotal information is used when solid research would have been more convincing.

Nonetheless, the report should give a few sleepless nights to some of the leading cast of characters mentioned.

In Kenya, theft of public funds is covered up through businesses that appear legitimate, but which use illegitimate means to grow.

A revealing article by the blogger Owaahh published in The Elephant recently suggests that the dwindling fortunes of the giant Nakumatt Supermarket chain may be directly or indirectly linked to the collapse of Charterhouse and Imperial banks, which were apparently being used to launder money and evade taxes.

TAX HAVEN

One of the majority shareholders of Charterhouse is Ram Trust, which also owns Nakumatt and is domiciled in Liechtenstein, a well-known tax haven.

Perhaps one of the reasons few investors have shown interest in saving this firm, says the author, is that it has been linked to dirty money.

One of the lessons we can learn from the Nakumatt saga is that a business built on illicit money cannot thrive indefinitely and will eventually hurt the economy.

Such businesses do not just impact the owners, but their many suppliers and employees too.

Here in Malindi, Nakumatt was until recently a bustling shopping centre where people of all walks of life mingled – a refreshing slice of urbanity and cosmopolitanism that is rarely experienced in this town.

Today, its shelves are almost empty and its tellers are idle. It is a sad sight to behold.