Observers must be as above suspicion as Caesar’s wife

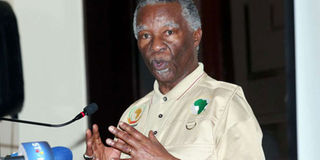

Mr Thabo Mbeki, the head of the African Union Election Observation Mission, addresses other election observers at a city hotel on August 4, 2017. Election-monitoring groups can boost voter confidence. PHOTO | KANYIRI WAHITO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- More than in any other election, the margin of victory is pivotal to securing post-election peace.

- Peace will largely depend on the tyranny of turnout to widen the margins.

Nairobi, Tuesday, August 9, 2022. Some 32 million Kenyan registered voters go to the polls to elect a successor to President Uhuru Kenyatta.

Deputy President William Ruto and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga are head to head as front-runners.

A local polling research firm predicts that the 77-year-old former premier might be the victor.

RUN-OFF

But the Ipsos Group, a global market research and consulting firm headquartered in Paris, France, puts the Deputy President in the lead.

The presence of three other strong candidates rules out first-round victory, forcing the election into a run-off.

However, the presence of strong political institutions has lessened tension, making Kenya’s democracy more certain.

East Africa’s largest economy has finally taken off, and Kenyatta’s legacy is assured.

TENSION

Since Kenya’s return to multi-party democracy in 1992, every subsequent General Election has been billed as “critical”.

So is the August 8, 2017 election. Peace is, again, on trial.

The 2017 election is occurring in a polarised environment fostered by intense and conflict-prone post-truth politics.

As earlier predicted in this column, the rise of “post-truth” global order has intensified tension in the elections (Sunday Nation, 25/2/17).

2022 ELECTION

A shrilly “last bullet theory” has created a false notion of a country teetering on the brink, contributing to tension and acrimony.

The last-bullet thesis is hoisted on the false premise that Odinga is old and sickly, and winning the 2017 election is a do-or-die affair.

The truth is that losing 2017 is not a big deal.

Odinga is still eligible to fight for the election in 2022 and 2037!

AGE

After all, Jomo Kenyatta was 73 when he ascended to power, and went on to rule the country for a full 15 years.

Kibaki came to power at the age of 71 and reigned for a decade.

Indeed, the ODM chief is just a year older than Donald Trump. 2017 might as well be a dry-run for his 2022.

POLARISE

Opinion polls of doubtful accuracy and integrity are proving too costly for peace — what Tom Wolf described as “poll poison” in an article published by the Journal of Contemporary African Studies (2009: 79-304).

These polls and the motives of those behind them have been rightly blamed for contributing to the polarised environment ahead of the 2007-2008 post-election violence.

Ahead of the August polls, a survey by Ipsos Kenya put President Uhuru in the lead with a popularity rating of 47 per cent while Raila is at 43 per cent.

RIGGING

But the Infotrak research firm — whose chief executive has denied accusations that she cooks polls and is related to Odinga — put Odinga ahead by one percentage point with the two at 47 and 46 per cent respectively.

Similarly, in 2013, Infotrak put Odinga ahead with 46 per cent against Kenyatta’s 44 per cent.

Although Kenyatta clinched a 50.51 per cent first-round victory against Odinga’s 43.70 per cent, the flawed poll results fuelled claims of “rigging”.

BREXIT

In 2017, other pollsters predict a victory for President Kenyatta between 4 and 21 percentage points, signalling the ideological biases and polarisation of pollsters.

Globally, the polls industry has lost its shine and reliability after pollsters failed to accurately predict the outcome of Brexit and victory of Donald Trump.

However, Infotrak and Ipsos polls seem to suggest a “run-off scenario”.

However, the truth is, there is absolutely no run-off in the 2017 presidential election.

STABILITY

The election is a perfect two-horse race that will be decided in the first round, averting a divisive and costly second round.

For rival political formations, victory in all positions is key to ensuring a stable polity to lay the foundation of peace, legitimacy and stability as pre-requisites for Kenya’s long-delayed economic take-off.

However, more than in any other election, the margin of victory is pivotal to securing post-election peace.

A narrow margin will most likely fall into the booby-trap of ubiquitous “rigging” claims and perhaps provide logic for “spontaneous” violence to force a power-sharing deal.

PEACE

Peace will largely depend on the tyranny of turnout to widen the margins.

Nevertheless, Jubilee will have a Herculean task defending a narrow victory and securing the nation.

An opposition loss throws up two scenarios. One, the opposition might opt to seek redress for its grievances in the corridors of justice, leading to either confirmation or rejection of the results by the Supreme Court.

ADOPT-A-POLLING STATION

Inversely, it might invoke “people’s power”.

With the failure of the run-off option, the alternative model is the “people’s president” installed through “people’s power” in the streets — as a contrast to “official president” announced by the IEBC.

This ideological fault-line is likely to define any post-election dispute.

The “adopt-a-polling-station” strategy, previously used in Ghana among other countries to mobilise a high voter turn-out, risks becoming a lightning rod.

TALLYING

The call by National Super Alliance (Nasa) to its supporters to remain at polling stations after casting their ballots to guard their votes against “rigging” risks triggering clashes between law enforcers and mobs.

Furthermore, the opposition’s parallel vote tallying strategy might also imperil peace if its results are used to declare victory as a “people’s president”.

Finally, election monitoring is key to democratic consolidation and peace.

OBSERVERS

The presence of over 5,000-strong world teams of election observers and hundreds of journalists from global news outlets who have joined over 7,000 local observers underscores Kenya’s geo-political and global importance.

As Thomas Carothers rightly observed, election-monitoring groups can boost voter confidence, improve election logistics, deter fraud, alleviate violence, and spread international electoral norms.

But election observation can prove a double-edged blade that can cut both ways.

IMPARTIAL

The presence of too many amateurs in the field, the excessive focus on polling day, and the frequently superficial judgements of “free and fair” without due regard for complex electoral environments can be a risk to peace and democracy.

Carothers lamented that election observers often fail to be impartial.

Election observations must, as a must, be as above suspicion as Caesar’s wife.

Ultimately, election observers must insist on strict adherence to the doctrine of peaceful transfer of power as the surest guarantee for post-election stability.

Prof Kagwanja is a former Government Adviser and Currently heads the Africa Policy Institute