Heavyweight division stuck in the doldrums

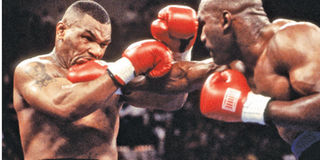

Mike Tyson (left) and Evander Holyfield trade blows during a WBA heavyweight championship fight on June 28, 1997 in Las Vegas, Nevada. PHOTO | FILE |

What you need to know:

- Welterweight world champion Mayweather remains the major attraction to ringside

- Once the most lucrative and entertaining of all prize bouts, top weight category is now in stasis

- Mayweather’s mix of brashness, skill and entitlement has earned him both ridicule and adoration. But as things stand, he seems to be the only soul keeping boxing alive.

There is a hilarious online video clip, an advert for the shoe and clothes retailer Foot Locker whose premise is an imaginary state where everything is possible. In it, former heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson rings the front door of Evander Holyfield’s mansion.

Eyes cast down and seemingly remorseful, Tyson thrusts forth his hand and gives Holyfield a small plastic box and mouths in his characteristic lisp, “I am sorry, Evander, it is your ear.”

The Tyson-Holyfield piece of course is in reference to the infamous bite incident that occurred on June 28 1997 when the two boxers met for the ‘Sound and Fury’ match, their rematch following Holyfield’s defeat of Tyson the previous year. During a clinch, Tyson bit a chunk of Holyfield’s right ear.

In a sense, that incident sounded the bell to signal the end of a colourful boxing age. Tyson, the most dominant boxer of his generation-if not all time, would never be the same again. He would be stripped of his boxing licence (which was reinstated in October 1998).

His comeback attempts were against journeymen and never-weres. Indeed, his last truly major fight was a lopsided loss against Lennox Lewis in 2002. By then, Tyson was a spavined version of his old self and no match for Lewis, who knocked him out in the eighth round.

THE AGE OF BLAND

Modern day boxing students would have to stare into space before combing good old Google if the question ‘Who is the current heavyweight boxing champion?’ were posed.

The once lucrative and most entertaining of all prize fighting, the heavyweight division is in stasis, characterized by blandness with no saviour in sight.

In the decade following the 2003 bout between Lennox Lewis, then the IBO and WBC title holder and Ukranian Vitali Klitshcko, the heavyweight championship has rarely passed hands. Wladimir Klitshcko, Vitali’s younger brother is the current WBA, IBF, WBO, IBO heavyweight champion and is the longest reigning champion in history.

While both are decent pugilists, the brothers’ boxing styles have been described as flat, lumbering and lacking in flair. But why isn’t the division selling out arenas anymore? Supporters of the Klitshcko brothers cite American cynicism, arguing that for the larger public, any boxer without an American passport or American ‘style’ (a euphemism for bravado and swagger) would be as flat as a can of beer left open overnight.

“They’re boring, they suck, they’re this, they’re that. They’re one of the big problems with boxing and (expletive) heavyweights nobody cares (about),” Dana White, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) President once ranted in an expletive-ridden tirade.

ROCK STAR FOLLOWING

In most of Europe, Wladimir has rock star following, and most of his fights on the Continent have sold out numerous stadiums. But outside Europe, the story is markedly different.

“I understand the criticism that the fights are boring, I get that,” Wladimir conceded in an interview. “…I am missing the fans in America.”

It is easy to forgive jaded fans used to sound bites and bombast that characterized much of boxing in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

The treatise is that for success at the box office, hype must precede the action, the build-up goosing up the ratings. Think the pre-fight press conferences between Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali; Tyson-Mitch Green; Lewis-Tyson.

Wladimir will never be accused of a surfeit of aplomb. He is decidedly blue-collar, nary any ink on his pelt, but endowed with a reliable jab. His press interviews are business-like, clipped.

Bloody as it is, boxing is equal parts skill and entertainment. Muhammad Ali was supremely gifted as a boxer, but he learnt early enough that the noise and ring antics (he perfected the rope-a-dope, floating and dancing) were the entertainment that crowds paid to see.

NO COME BACK

In an interview with the British tabloid Mirror in 2012, retired boxer Lennox Lewis, considered by many the last true heavyweight scoffed, said:

“People keep asking me if I’m coming back because there’s only one fight out there the Klitschkos can sell. But unfortunately for them, it’s against a 46-year-old who retired eight years ago and the answer is no, I’m not making a comeback.”

The simple fact is that there is hardly any talent likely to dislodge the 38-year-old Wladimir from the throne he has held for close to a decade; no saviour galloping from the horizon to yank the division from the doldrums.

The only heavyweight boxer with a whiff of a chance is 35 year-old Haitian-Canadian Bermane ‘B. Ware’ Stiverne, the WBC champion. Stiverne, known for his sibilant left hook, knocked out Chris Arreora in the sixth round in December 2013 to win the WBC title, vacated by Wladmir’s elder brother Vitali. A possible bout between Stiverne and Klitschko is scheduled to take place before the end of 2014.

In addition to questionable talent, the heavyweight division has seen a proliferation of dubious championship belts. Currently, there are 37 sanctioning bodies, each with its own version of the championship belt.

THE GOLDEN AGE

Ever since the ‘mouth from the south’ Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, laced up a pair of and upended the burly Charles ‘Sony’ Liston in 1964 in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history, heavyweight boxing entered a lush era that would captivate fans for decades.

The 2009 documentary Facing Ali - a revealing film focusing on the lives of boxers who fought Ali and how the encounter with ‘the greatest’ altered their lives - throws open the window to a boxing era that may never be replicated.

From the mid ‘60s to the early ‘80s, the heavyweight division spawned the greatest generation of fighters: Smokin’ Joe Frazier, George Chuvalo, George Foreman, Ken Norton, Ron Lyle and Larry Holmes.

For these fighters, the sport was deeply intertwined with personal grudges and the right of ascent and defined by the politics of the day.

None however played out deeper than the Ali-Frazier rivalry. The America of the ‘60s, with its potent mix of racial strife and the Vietnam War cast both Ali and Frazier on opposing ends.

In 1967, Ali, who was by then undefeated, was stripped of his belt and banished from the sport after refusing to be drafted into the Army, which would have seen him fight in Vietnam, famously saying he ‘had no quarrel with them Viet Cong’.

During Ali’s limbo, Joe Frazier ascended to the championship with his devastating left hook. During this period, Frazier befriended Ali and supported him, even lending Ali money and during a visit to the White House petitioned President Richard Nixon on behalf of Ali to have the licence back.

That changed after Ali regained his licence. Ali, who by now was revered as a martyr and hero, immediately rolled out a humiliating campaign against Frazier, branding him, among other names, a gorilla and castigating him as an Uncle Tom (derogatory for a submissive black man).

This set the stage for Ali-Frazier 1, which came to be known as ‘The fight of the Century’ in 1971. Frazier won by a unanimous decision after flooring Ali in the 14th round. The hyphenate that joined the two boxers would forever define the ‘70s.

The last of the Ali- Frazier trilogy was held in Manila, Philippines in 1975. Dubbed the ‘Thrilla in Manila’, the fight went fourteen rounds, until Frazier’s corner stopped the fight. Ali would later say it was the closest he had ever come to dying.

Perhaps the biggest upset of the ‘70s was the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ between Ali and Foreman that was staged in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) on 30th October 1974. Foreman, considered the greatest puncher of all time was the favourite to win.

But Ali, using his speed evaded Foreman’s reach, wearing his opponent out and finished him off with a combination of punches that put Foreman on the canvas in the eighth round. In the middle of all this was promoter Don King.

Even as fighter after fighter entered and exited the ring, the omnipresent King, with his shock of hair and Svengali-like hold on his charges, could always be counted on to pull unlikely matches, even as his machinations blighted the finances of some of his fighters.

As the grizzled warriors of the ‘70s faded, a young fighter who would define the mid ‘80s and the ‘90s took over the reins. In 1986, Mike ‘iron’ Tyson exploded on the scene with unparalleled rage, athleticism and punching power.

From 1986 to 1990 when he suffered his first pro defeat by James ‘Buster’ Douglas in Tokyo, Japan, Tyson was unstoppable, flooring his opponents with almost macabre efficiency, and rightfully earned the title of ‘baddest man on the planet’. Outside the ring, Tyson never lacked for colour. His off-ring trouble, disastrous marriage to actress Robin Givens and his three-year jail term, resulting from an alleged rape of beauty pageant Desiree Washington provided a steady supply of grist for the rumour mills.

By the time Tyson was locked away, a dream match-up with Holyfield was in the books. The fight would be delayed until June 1996, following Tyson’s parole in 1995.

Holyfield, a tested warrior, having beaten Douglas, Riddick Bowe and an aged Foreman, was however never considered a match for Tyson. The boxing world was stunned when he stopped Tyson in the 11th round.

Lennox Lewis dominated most of the late ‘90s and early this century, scoring wins against Holyfield, Hasim Rahman, Vitali Klitschko and retired with a record of 44 fights, 41 wins, 32 by knockout, and one draw.

For close to a decade now, the major draw in the boxing arena has been Floyd ‘money’ Mayweather, the reigning welterweight champion, who has won ten titles in four different weight classes.

Floyd Mayweather Jr. throws a right to the face of Marcos Maidana during their WBC/WBA welterweight title fight at the MGM Grand Garden Arena on September 13, 2014 in Las Vegas, Nevada. PHOTO | AFP

Mayweather’s mix of brashness, skill and entitlement has earned him both ridicule and adoration. But as things stand, he seems to be the only soul keeping boxing alive. And lively.

Few people are pencilling their calendars for a heavyweight bout.