Superstar, moral icon, the greatest of all time

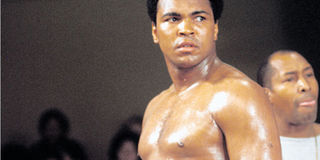

A photograph dated May 15, 1975 shows US heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali (front, left) during a training session prior to his bout against England's Richard Dunn in Munich, Germany. PHOTO | ISTVAN BAJZAT | DPA

What you need to know:

- Muhammad Ali was not just the greatest boxer who ever lived. He was also the greatest poet who made us imagine that we could magically “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee” in the school boxing club before we came down to earth extremely hard.

When US President Jimmy Carter decided that America, its allies and assorted client states around the world would boycott the 1980 Olympic Games as punishment to the then Soviet Union for invading Afghanistan, he sent Muhammad Ali to Kenya to talk President Moi into falling in line.

Reeling from a similar politically-inspired boycott in 1976, the last thing any Kenyan sports lover wanted to hear of was just that word. It seemed as if for political expediency, the world was conspiring to destroy what Olympism sentimentally calls “the youth of the world”, even as it continued to keep trade and diplomatic ties intact.

Anybody coming to Kenya on such a wildly unpopular mission would have faced an exceedingly cold public reception. But not Muhammad Ali – and Carter obviously knew it. Despite ourselves, we temporarily forgot what he had come to Kenya for and crowded around him. We desperately wanted to have our pictures taken with him. We followed him wherever he went.

We loved his antics; at State House, just before posing for an official photograph with Moi, he pointed with a quizzical expression at the President’s ivory baton. Moi held it out as if to explain. Ali took it smoothly, posed exactly as Moi usually did and motioned to the photographers to proceed. There was a howl of laughter from all around although I noticed some party functionaries wearing expressions of anxiety. It must be the only time in his life that Moi posed officially with somebody else holding his fimbo ya Nyayo.

The greatest athlete in the world, and for some of us, the greatest in the history of humankind, was among us – and it was a special feeling. He performed in the pre-twitter and pre-facebook age, but as schoolchildren and later as journalists, we felt him intimately among us as he won and lost his epic duels in the ring, and as he took on the might of the US government in courtrooms and in the lecture circuit in America’s Ivy League universities. He was not just the greatest boxer who ever lived, he was also the greatest poet who made us imagine that we could magically “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee” in the school boxing club before we came down to earth extremely hard. Today, transient topics trend; to us Muhammad Ali was trending almost every day. To millions of people in the world of a certain generation, he will trend to the ends of their own lives.

Since the announcement of his death early yesterday, these people are consumed with grief. But I also know that this sorrow is also punctuated every now and then with raucous laughter for Muhammad Ali was also the person who could drag laughter out of the most reluctant person. He didn’t just make fun of other people; he also made fun of himself a piercing humility always lurked behind the avalanche of bombastic words that he directed at his opponents.

“He did not just shake me,” Ali said after British heavyweight Henry Cooper hammered him with blows that sent him to the canvas and held on to the dying rounds of their 15-round bout. "He shook my relations in Africa.”

All sport, as with many other endeavours in life, goes with ages. Boxing is now in decline worldwide. Its golden age was during Muhammad Ali’s time. And he was in the middle of the three greatest duels of all time – the Fight of the Century against Joe Frazier in Madison Square Garden in 1971, The Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman in the then Zaire in 1974 and the Thriller in Manila in the Philippines again against Frazier in 1975.

What is remarkable is that Ali reigned atop the pile of history’s best fighters. Foreman and Frazier were his match – but only in the ring; not as anything else.

Ali elevated boxing to more than just a duel in the ring. He took the craft to the realm of politics and social justice especially with his 1971 fight against Joe Frazier. This bout became a watershed event in the political discourse of the United States and the world.

In the 1960s, it was mandatory for young people to join the United States armed forces. It was called the draft. And at that time, the US was involved in costly war in Vietnam that would ultimately result in the deaths millions of Vietnamese and 58,000 American soldiers. In 1967, aged 25, Ali objected and the ultimate master of the pithy quote and rhyme had a memorable reason for his conscientious objection.

“I ain’t got nothin’ against them Viet Congs,” he said, referring to the North Vietnamese whose whole villages and towns were being wiped out in an aerial American campaign called carpet bombing. “They don’t call me nigger.”

That simple sentence brought into sharp focus the racism and social exclusion of blacks in the United States. He became a rallying point for objectors to the war, who numbered in the millions. For this reason, supporters of the ill-fated Vietnam campaign rooted for Frazier, who frankly didn’t understand or care about what was going on.

In 2005, when receiving America’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush, there was a small yet loud echo of what Ali had done 38 years previously; a protester from the Hurricane Katrina- ravaged New Orleans held up a sign reading: “No Iraqi left me on a rooftop.” She was protesting the Iraqi war.

I have heard uncountable descriptions of Muhammad Ali but one made by filmmaker Spike Lee tops them all for me. “He was this beautiful specimen of a fighting machine. He was handsome, he was articulate, he was funny, charismatic, and whoopin' ass too,” he said in the documentary film When We Were Kings by director Leon Gast about the Ali versus George Foreman fight.

Yet again, nobody could describe Ali better than Ali himself. His bravado, his self-assurance, his wit and his outrageous claims mean every watching of a film on him is more interesting than the last time.

“I'm young, I'm handsome, I'm fast, I'm pretty and I can’t possibly be beaten!” he told bemused listeners. “Some people say I'm cocky, I talk too much, I need a good whippin’, but everything I say I'm willing to back up.”

And that was not all. What were his capabilities? What was he going to do to George Foreman? “I’m bad! (Note that in American slang, bad means exceptionally good). I’ve done new things for this fight. I’ve been chopping trees! I’ve wrestled with an alligator! I’ve tussled with a whale! I’ve handcuffed lightning and thrown thunder in jail! That’s bad! I’m bad! Only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalised a brick! Bad, man, bad! I cut the light of my bedroom, hit the switch and was in bed before it was dark. Fast, fast, fast! I mean, I’m so mean I make medicine sick!”

Mean he could be in the real sense of the world. Howard William Cosell, the self-centered ABC sports commentator, said before the Foreman fight that Ali was already over the hill. He was too old to make any impression against a young George “who does away with his opponents in just a couple of rounds.”

Cosell had picked on wrong man. Wagging a menacing finger at him, Ali barked: “You say Muhammad Ali is not the same man he was 10 years ago? Well, I asked your wife and she told me that you were not the same man you were two years ago!”

But Ali was also capable of the sublime. And it was George Foreman who brought it out as only a man as strong, charitable and good natured as he was could. Foreman was describing his devastation at losing his world heavyweight championship title to Ali in that unforgettable Rumble in the Jungle. Then he said poignantly: “The best punch of that fight was the one that was never landed. As I lost balance and staggered backwards with my guard down, Ali had his right hand perfectly placed to finish me off. But he held back and let me fall on my own. That, to me, made him the greatest fighter of all time”.

Joe Frazier is the man who took Ali to the very gates of hell. He never could fall, regardless of the pounding he took. In the Thriller in Manila in 1975, so named because Ali the peerless poet had declared that the fight would be a “killa and a thrilla and a chilla, when I get that gorilla in Manila” he kept begging him in the closing rounds: “Joe why don’t you quit?”

Frazier, who was already blind and was fighting by instinct, replied: “I won’t. I want your title.” Because of the extreme punishment that he had suffered, Eddie Futch, Frazier’s manager, stopped him from coming out for the 15th and final round.

Ali later called Frazier’s son Marvis to his dressing room and apologised for any insult he had ever directed at Frazier, pleading that whatever he said had been meant to promote their fights. He begged Marvis to obtain forgiveness from his father on his behalf.

Two days ago, news reports came through that Ali, 74, had been admitted in hospital with respiratory problems. His family was said to have been advised to prepare for the worst. I instinctively did the same while hoping for the best. But he is gone. He now belongs to the ages and leaves us with memories that transformed humankind. His passage through the gates of heaven is truly deserved.