Chapecoense tragedy unites football world in mourning

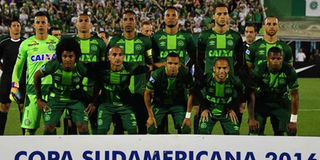

This file photo taken on November 24, 2016 shows Brazil's Chapecoense players posing for pictures during their 2016 Copa Sudamericana semi-final second leg match against Argentina's San Lorenzo held at Arena Conda stadium, in Chapeco, Brazil. A plane carrying 81 people, including members of a Brazilian football team, crashed late on November 29, 2016 near the Colombian city of Medellin, officials said. PHOTO | NELSON ALMEIDA |

What you need to know:

- Spectacular misfortune brings out the vulnerability that resides in all of us in the open and forges a unity between us. The recent air crash involving the Brazilian club that claimed the lives of 19 players has seen an outpouring of love and sympathy

- Fifa has decreed that this weekend, every football match in the world starts with a minute silence tribute to the dead.

- Players have also been asked to wear black armbands.

- Silence will also be observed before next week’s Champions League and Europa League matches.

Before last Monday, few of the most ardent of football fans in Kenya and around the world had ever heard of the name Chapecoense Real. But after the air crash that killed 19 of their players travelling to Colombia for the first leg of the Copa Sudamericana tournament final, they are in the lips and thoughts of millions of people in all five continents.

Fifa has decreed that this weekend, every football match in the world starts with a minute silence tribute to the dead. Players have also been asked to wear black armbands.

Silence will also be observed before next week’s Champions League and Europa League matches. On Tuesday and Wednesday this week, before the quarter finals of the EFL – English Football League - Cup quarter-finals, similar tributes to Chapecoenses’ fallen were observed.

Tragedy brings out the vulnerability that resides in all of us in the open and forges a unity between us, however momentarily, that nothing else in life can.

It brings out the best in us, and amid the tears we suppress in other distressed circumstances despite the restoring value of their shedding, we commit acts of charity that are profound in their humanity. It is happening right now as Brazil buries its footballers, technical staff, journalists and the other people aboard that doomed plane.

EXEMPT FROM RELEGATION

It started with the country’s big clubs offering to loan Chapecoense players free of a charge for one season. Then there was the petition to the Confederation of Brazilian Football (CBF) to exempt Chapecoense from relegation for three seasons as it embarks on the arduous journey of rebuilding its decimated ranks.

For their part, Chapecoense’s would be opponents, Atletico Nacional requested the South American Football Confederation (Conmebal) to award them the game and declare them champions and marked the time the final would have started with a massive wake at their Girardot Atanasio Stadium in Medellin where the game would have taken place.

And then came the dramatic news that legends Ronaldinho Gaucho and Juan Roman Riquelme may come out of retirement to play for Chapecoense.

Ronaldinho, a Brazilian World Cup winner in 2002, was the World Player of the Year in 2005 while Riquelme was Argentina’s Footballer of the Year four times.

These acts of charity are not new whenever the beautiful game is hit by tragedy. On October 6, 1958, a charter plane carrying Manchester United crashed as it attempted a third take-off at Munich Airport in Germany.

Of the 44 people on board, 20 died at the scene, followed by three more in hospital. It would take United 10 years to return to full strength but before that, top rivals Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, offered to loan them players free of charge in the rebuilding process.

Against this overwhelming responses to Chapecoense’s travails, I was distressed to remember that when the Zambia national team was wiped out in a crash off the Libreville in Gabon en route for a World Cup qualifying match against Senegal in April 1993, it was the Zambia FA that requested Fifa for a three-month grace period to enable it build another team. And Africa’s response, of course, went no further than messages of condolence.

When going over the tributes the world is showering upon Chapecoense, I remembered an extraordinary one that followed United’s tragedy. That crash killed England’s best player of the day, a precocious youngster named Duncan Edwards. Arthur Walmsley, in the 1968 book, “Soccer: The Great Ones”, captured the essence of what football teams and the individual exponents of this game evoke in the imagination of their followers. They are larger than life.

Some in England reacted to Edwards’ death with an unusual tribute. Walmsley writes: “On a sunny day in the small Worcestershire town of Dudley, the red of Manchester United and the white of England beam from a stained-glass window in the church of St Francis. It is a church window unique in Britain – probably in the world – for it glorifies a footballer among the saints.

“From the top two of the window’s four sections, St George and St Francis gaze down benignly on twin figures of Duncan Edwards depicted in soccer strip – one figure in the red of Manchester United, the other in the colours of his country.”

Some Christian faithful were appalled by what they saw as a shocking alliance with all its irreverence, a canonized pair enjoined with a professional footballer. But the Bishop of Worcester couldn’t disagree more. He said: “Duncan and players like him have given people all over the world a fine example of the British way of life. I am sure that instead of constant meetings between the politicians which seem to increase tension, we could solve the Berlin situation much more easily by sending over football teams for a tournament.”

CHURCHES EMPTY

The church seemed to go too far, but social trends in Europe pointed in the opposite direction. More and more people were going to football matches and less and less of them were going to church. Today, many churches across the continent are empty and some have been converted into sports and night clubs. In contrast, tickets for matches in Manchester United’s Old Trafford, Arsenal’s Emirates, Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabeu, Bayern Munich’s Allianz Arena and many others are sold out across the year. The football stadium is the new cathedral and the football star the new saint.

The Bishop of Worcester had seen it coming in the 1960s.

In 1984, Time Magazine journalist Roger Rosenblatt wrote a brilliant essay titled: “Do you feel the death of strangers?” In it, he discussed the famous words of the mediaeval English poet and cleric, John Donne, who once proclaimed: “Any man’s death diminishes me.”

Rosenblatt wrote: “Donne’s thesis was that human sympathy ought not to be what we dust off occasionally but what we display all the time. Thus would we weep not only for death at a distance but for the sufferers who are closer at hand, for the family down the street whose plight goes unnoticed and untelevised – for all those in fact whom we might actually help.”

I agree. Next to us are people whose deaths we are contributing to by nurturing and constantly celebrating a culture of theft of public resources that condemns some our people to a life far beneath in quality to that of animals roaming our national parks.

Some are footballers and many are not. But they are all our compatriots. And our messages of condolences, those rehashed and worn statements about somebody’s death being a loss not only to one’s family but to the country as a whole, ring hollow when we could do so much more with all the human and material resources at our disposal. We can do more with a bigger conscience. We can cultivate a stronger moral fibre.

As we mark the passing of Chapecoense’s fallen, let’s think of what practical use we can make of one of my favourite mottos of all time: Liverpool Football Club’s ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone.’