Seraphino Antao: Destiny denied champion sprinter Olympic glory

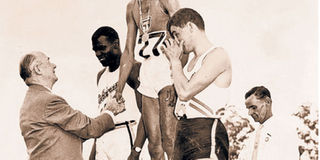

Seraphino Atoa (centre) after receiving his 100 yards gold at the 1962 Perth Games. PHOTO | COURTESY |

What you need to know:

- Mombasa speedster captured imagination of the world after daring to race against a cheetah Why me? He was leader of the team and in peak form at the 1964 Tokyo Games but fell sick on eve of competition

- Prime Minister Kenyatta went gaga when the flying Kenyan won gold in the 100 yards and 220 yards at the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth, a historic achievement for Kenya in international sports at that time

This is the telegram – yes, telegram, not SMS, email or WhatsApp – sent by Kenya’s Prime Minister Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, to Seraphino Antao in 1962:

TO SERAPHINO ANTAO COMMONWEALTH AND EMPIRE GAMES PERTH

YOU HAVE REALLY BECOME KENYAS PRICELESS JEWEL IN SPORTS AND SHINING ATHLETICS STAR STOP PLEASE ACCEPT OUR PROFOUND APPRECIATION OF YOUR TREMENDOUS SUCCESSES STOP KENYA SHALL ALWAYS BE PROUD OF YOU STOP

CONGRATULATIONS

JOMO KENYATTA +

If you belong to the digital generation, please ask Google, man’s new best friend, how telegrams worked. But for now, just note the capital letters and the absence of any punctuation marks. So much for instant communication in 1962.

Seraphino Antao, who died of cancer in London in 2011 aged 74, was Kenya’s first international athletics champion. He also heads the list of superstars who never won an Olympic medal even if they could.

In his case, it was the result of the vicissitudes of personal destiny; he was the flag carrier for the 1964 Olympics, a task reserved for the outstanding athlete. And then he got sick just before the competition started. In the case of the majority of his successors, it was politics beyond their control – Kenya boycotted the 1976 and 1980 Olympics.

Antao was an original, atypical Kenyan champion. He was a sprinter in a country that would dazzle the world for decades with a succession of distance runners some of whom were described by mesmerised foreigners as being possessed of mysterious talent.

In the Perth, Australia Commonwealth Games in 1962 – the subject of the foregoing telegram – he won gold medals in the 100 yards and the 220 yards.

They were the first gold medals won by any Kenyan in a major international competition; a tremendous success, as the President told him, and one for which Kenyans have been justly proud.

His winning times in those events were 9.5 sec and 21.1 sec respectively. He also anchored the Kenya 4x440 yards team that finished fifth in the final.

Antao was a native of Mombasa.

He was born in the Makadara area but was raised variously in Ganjoni, Makupa and other places because his father Diogo Manuel, who worked for the East African Railways and Harbours, kept moving from place to place.

To the end of his life, even after a 40-year absence from home, Antao retained the distinct accent of Coastal Kiswahili, which he spoke fluently.

Manuel had immigrated to Kenya from Goa in the early 1920s and in Kenya met Anna Maria, whose parents had also come from the same place.

Together, they had five children, Antao being the first born. The young Seraphino became an obsessed football player and may well have gone far in the game where he would have been in good company; another Kenyan of Goan dissent, Saude George, was already playing for the Kenya national team during the 1950s.

In a contribution that was out of all proportion to their numbers, players from this community would later play a dominating role in a variety of sports in Kenya during the early independence years, especially in hockey, before migrations to Britain, Canada and Australia took their heavy toll on the national sports scene.

NO TURNING BACK

Other members of the community became prominent in sports journalism.

Antao’s foray into athletics was entirely accidental. In 1956, while working for the Landing and Shipping Company, an agent of the East African Railways and Harbours, he entered an athletics competition and took part in the sprints. He won both the 100 and 220 yards easily and discovered a gift that was not apparent before. And from there onwards, there was no turning back.

By the following year, he was the national champion in these events and was a member of the Kenya team to the 1958 Cardiff Commonwealth Games and 1960 Olympic Games in Rome.

His exploits in Perth in 1962 catapulted him into the league of legends and he was the natural leader of the team to the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. And then disaster struck.

Not long before his death, Jackie Lebo, the athletics expert and documentary film director, visited Antao in London and found a grey senior citizen wallowing in nostalgia about the land of his birth.

Everything in the house, from the big Kenya flag covering the living room wall, to the photographs of his career exploits, to his scrapbook – spoke of a man whose life was dominated by his illustrious past.

Of the photographs, one of the most arresting ones was the one depicting him racing against a cheetah in a stunt set up by photographer Akhtar Hussein (40 years later, this race would be recreated with Bryan Habana, the speedy South African rugby star).

Only a man of Antao’s unusual gifts could inspire in some people the imagery of a race against the world’s fastest land mammal, which can reach a top speed of 120 kph in one short burst. Of course, the sleek cat beat Antao, but it was lots of fun besides inspiring romantic thoughts of trying to attain the seemingly unattainable.

Why did Seraphino Antao quit at only 27 shortly after the Tokyo Olympics? He told Lebo: “I had had enough of it. In Tokyo, I fell ill on the eve of the opening ceremony. That was it. All my hard work had gone. I wanted to win some sort of Olympic medal, and I was favoured to win something. I was fed up of training six days a week. Eight years. Top class at four or five events. It is not easy. You get fed up.”

How familiar. We always marvel at stupendous athletic achievement and we want it to go on and on. We also look on with envy at the huge sums athletes take home as pay. But few of us stop to think of the price at which that success is achieved. Essentially, it is life as lived in ancient Sparta.

It is a daily grind of training, training and more training. It is a life of rigorously following a prescribed diet, even when it is one you cannot stand.

It is a life of waking up with the early birds, whether or not there is a torrential downpour outside and the comfort of the soft and warm bedding is delicious beyond description. It is a life, if offered to many of us, we would break a leg running away from.

It was Drew Bundini Brown, Mohammad Ali’s trainer, who once described it thus: “We wake up sometimes feeling good, sometimes feeling bad. This ain’t Hollywood; Hollywood just make things up. This is real, man, this is real. This is God’s act, man. We’re just actors in it. This is real. This ain’t made up.”

God’s act had finally reached the marrow of Antao’s bones and he couldn’t take it anymore, however much people wanted to marvel at this Mombasa cheetah on two feet. He opted to retire in Britain and 40 years later in 2003, he returned home to take part in celebrations marking 50 years of Athletics Kenya.

It was an emotional re-union with athletes of his generation, Nyandika Maiyoro, Kipchoge Keino – who succeeded him as flag bearer of the Kenya team – Joseph Lerasai, Naftali Temu and others. Then he took time off to visit his childhood home in Mombasa.

Like Julius Yego today, Antao was where everybody else was not. And while at it, winning. He was an atypical champion – a sprinter from sea level in a land of distance runners from high altitudes.

Five years since his death and in this Olympic year, he still represents all that is possible. To those given to making excuses, for just this minute, picture in your mind a man racing against a cheetah. Where did that come from? It came from that unfathomable place inside you that makes you look at a hopelessly impossible situation and still say in quiet belief: it is possible.

*****

At the start of this Olympics series, I invited readers to share their most memorable recollections of the Games with me. This week, I share the experience of one John Gachoya who wrote:

“Your article in the Saturday Nation – Kenya’s Olympic Games journey glows like gold – is very good. Thanks for taking us back along memory lane. I look forward to your subsequent articles. Let me relate an incident that happened when I was in Standard 7 in 1963. A person came to our school and, before we knew what, we were herded by our teachers into one classroom to listen to his story. He claimed that he had been to Tokyo in Japan where he had participated in the Olympic Games. Well, he did not have a single souvenir, much less a medal, to show but he regaled us with tales of how he had won races. In those days, I used to listen to the radio a lot and I knew that the Olympics were to be held the following year – 1964 - but being so young and with the teachers and everybody else thoroughly enthralled by his story, I could not point out this. To this day I do not know what the man wanted but we soon came to learn that he was going around schools relating the story.

It then transpired that he had never been outside our country let alone being anywhere near Tokyo.

The man soon disappeared, just like the way he had appeared, never to be heard of again. But maybe you can clarify one thing: I seem to remember that in the early days, a city hosting the Olympics would stage a rehearsal the year before. If so, the conman had taken advantage of the rehearsal to come up with his story. But I repeat: he had never gone outside Kenya.