Henry Rotich: The man who plays safe by never saying ‘No’

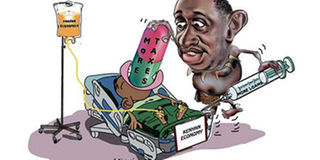

Most economists would cringe at any extravagant expenditure, not so Mr Rotich, the man who unveiled this year’s budget on Thursday. ILLUSTRATION | JOHN NYAGAH

What you need to know:

- To be fair, his predecessors were also borrowing. But when he took over from Njeru Githae in 2013, his predecessor was borrowing about Sh115 billion every year.

- At Sh600 billion a year, Mr Rotich is borrowing at a rate that is five times more than his predecessors.

- He took over when the country had stopped over-reliance on budget support, but has reversed this.

- He has made the controversial Eurobond now a necessity in government finances. In the past five years, at least Sh680 billion came from only this one source.

Henry Rotich, the economist plucked from a low-profile job at the macroeconomics department of the National Treasury six years ago to be the centrepiece of Kenya’s finances, is a man who finds it hard to say no.

TAKES ORDERS

Faced with two decisions, Kenya’s most powerful public financial officer will run with the option that brings to his doorstep the least problems, in the short-term.

Most economists would cringe at any extravagant expenditure, not so Mr Rotich, the man who unveiled this year’s budget on Thursday.

He would rather take a new loan to fund the latest item on the government’s wish list, even when data showed the country could least afford it, than stand firm and say “No”. While some may say he is a mere pawn in Jubilee’s debt chess game, others say he is an enthusiastic facilitator.

For example, pushed into a tight corner, he let MPs lay their hands on funds to pay themselves hefty house allowances at a time when all revenue indicators in the country were flashing red.

The fact that it was an outright violation of the law did not count. He released the money on demand. It would be their problem defending those perks, not his.

Those who work closely with him say he is a man who has been misunderstood. They say the media has been too harsh on him. He just takes orders from above and implements them without question once Cabinet approves them. They argue he should not be the one to blame for taking the economy on life support.

He is not the combative type, say his backers, and prefers to raise his concerns behind the scenes, a perfect quality in government employees.

“You would not even know he was in his office unless you opened the door,” said a confidant who declined to be named in order to speak freely. That Mr Rotich has an impressive CV is not in doubt. His grades right from primary school, all the way to his two master’s degrees —one earned abroad—reveal an extraordinary student. Unlike most technocrats who call the shots at the Treasury, his is a story of humble beginnings.

VALUE ADDED TAX

Mr Rotich must have seen the ugly face of poverty as he walked to Fluorspar Primary School in Keiyo South where he was always top of his class. So he should find no difficulties relating to problems of the common man who is easily battered by any rise in the cost of living. It must have been at St Joseph’s High School where he was shaped into a man who dreams of possibilities and hates to disappoint people.

His being too eager to please has worked for him at times. In his early days as the Treasury boss, he easily convinced Parliament to increase the country’s borrowing limit, a decision that would later come to haunt the country.

He also got MPs to support an unpopular decision of introducing Value Added Tax (VAT) on food, fuel and other basic commodities, despite public uproar.

But it is also one of his greatest weaknesses that nearly destroyed his career this year, after the dam scandal became public. Questions were raised over huge payments made for the Arror and Kimwarer projects in Elgeyo Marakwet County yet no work had been done. He would retreat away from the public and even missed important trips to China that on a normal day a Treasury boss would never miss.

Whether or not his story convinced detectives from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) that he was an innocent man remains a matter of conjecture.

Wounded, he is fighting back his way into the heart of government. There is nowhere better to do this than at the centre of the distribution of the national cake.

LITTLE ACCOUNTABILITY

When he presented his seventh budget statement in Parliament on Thursday, just like the previous spending plans, he was honest, and acknowledged that the government wage bill, pension and other items in its recurrent expenditure were a threat to the financial health of the nation.

However, it is not the first time he has promised that his ministry would moderate spending and ensure cautious revenue projections, in an effort to limit borrowing. Cutting down on borrowing has been one of the most difficult promises for him to keep.

The National Treasury, under his leadership, has sanctioned excessive borrowing despite little accountability on where the billions borrowed have exactly been going. Today, for every Sh100 Kenya is collecting in tax revenue, it is spending at least Sh130 to remain afloat, an overspending that makes borrowing inevitable. Mr Rotich took charge when public debt was at Sh1.7 trillion. He has comfortably presided over a department that has grown this by three times in the past five years to Sh5.1 trillion. This is an increase of Sh3.4 trillion and translates to a borrowing of about Sh600 billion every year or Sh50 billion every month, the fastest accumulation of debt in Kenya’s history.

To be fair, his predecessors were also borrowing. But when he took over from Njeru Githae in 2013, his predecessor was borrowing about Sh115 billion every year. At Sh600 billion a year, Mr Rotich is borrowing at a rate that is five times more than his predecessors. He took over when the country had stopped over-reliance on budget support, but has reversed this. He has made the controversial Eurobond now a necessity in government finances. In the past five years, at least Sh680 billion came from only this one source.

He has always used any chance he gets to point out that the debt is sustainable and that it is always put to good use.

RED SIGN

But if you probed him further to provide a list of all the projects the debt is going into, or an easier question on evidence that indeed all the debt billions are only going into development projects, he would find the best way to mumble himself out of it.

It is only him and a few other individuals at the national Treasury that believe everything is fine. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) said something is not right last year when it flashed the first red sign and revised Kenya’s risk of external debt distress from low to moderate.

“This reflects the breach of three external debt indicators—external debt service-to-export ratio, external debt service-to-revenue ratio, and the present value of external debt-to-export ratio – for an extended period of time under the most extreme shock,” IMF said.

A number of economists and financial experts including the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) itself have said it is time to slow down and ease up on debt. Mr Rotich previously worked at the research department of the CBK and had a three-year stint at the IMF local office in Nairobi, where he worked as an economist.

He has been a director on several boards of State corporations among them the Insurance Regulatory Authority, the Industrial Development Bank, the Communications Authority of Kenya and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS).

His second master’s degree is in Public Administration from the Harvard Kennedy School in the US. He has another master’s degree in Economics and a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics, both from the University of Nairobi.