Breeding method that ensures you get milk all the year round

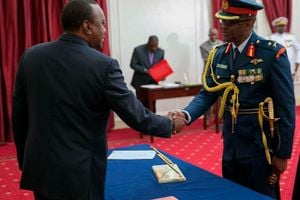

Charles Wathobio in his goat farm in Rongai, Nairobi. PHOTO | LEOPOLD OBI |

What you need to know:

- Synchronised breeding works well for a farmer who wants to raise a number of calves or kids at the same time.

Inside a wooden pen somewhere in Rongai, on the outskirts of Nairobi, some 15 goats wearing yellow plastic tags that resemble earrings chew hay while others lounge on the wooden floor chewing cud.

Adjacent to the pen is another holding five kids — all six months old — drinking milk from a bucket.

“Five of the does are lactating,” says Charles Wathobio, the proprietor of the dairy goat farm. “They all gave birth at the same time.”

Wathobio practices what is known as synchronised breeding, a system of farming that enables him to have several of his goats calve down at the same time. The practice ensures that he has constant supply of milk all-year round.

He starts by identifying the does that he would inseminate.

“Normally, I pick five does that I serve using artificial insemination method. I get the semen from Egerton University‘s Department of Animal Production.”

After the does calve down, the day-old kids are separated from their mothers and then introduced to bottle and later bucket-milk feeding.

“This allows me to get plenty of milk from the animals. Each goat offers six litres a day. Right now I get 30 litres every day that I sell at Sh200 each.”

As the kids grow, the farmer then selects another batch of five does, which he inseminates.

“There is no time you will come to my farm and miss milk. I embraced the method that I learned after doing research online because demand for goat milk is high.”

CAN BE EXPENSIVE

Synchronised breeding, according to Prof Erastus Mutiga of University of Nairobi’s Department of Animal Production, works well for a farmer who wants to raise a number of calves or kids at the same time.

“The farmer will be able to simultaneously raise a bunch of animals thus have several to sell. He also gets milk throughout the year because as he stops milking one group of goats, the next is ready.”

Prof Mutiga, however, notes that the method can be expensive in terms of cost and labour.

“One spends a lot of money on artificial insemination when serving a group of heifers or mature does. Then after the animals calve down, you have several others to take care of, which can be costly.”

The expert, however, notes the method is rewarding.

According to Wathobio, anyone practising synchronised breeding must keep up-to-date records.

“It is the reason that all my animals have ear tags. The tags show the animals’ name, when they were served and semen from which bull. It helps me when I am selecting a doe to serve,” says the farmer, who went into commercial dairy goat rearing five years ago.

From the tags, he is able to know the goats with impeccable breeding traits, like those that get pregnant easily.

The 41-year-old started with one Alpine dairy goat that he bought at Sh18,000.

Soon, the doe gave birth and neighbours started to buy the milk from him.

Increased demand for the milk that is highly nutritious saw him expand his brood and he went commercial under the name Rongai Dairy Goat Farm.

He sells a mature Alpine goat at Sh30,000.

MAINTAIN HYGIENE

“Dairy goat keeping requires little space as one only needs to construct a wooden barn with a corrugated iron sheet roofing, which might need roughly Sh35,000 to put up,” says Wathobio, who keeps the 20 dairy goats on his eighth-acre plot.

He notes that a barn should have a wooden floor and be raised at least 12 inches above the ground to maintain hygiene and keep pests at bay.

“A pen should never be damp to avoid respiratory diseases like pneumonia,” according to the farmer, who has another herd of 40 dairy goats in Nyeri.

He notes that the animals should be dewormed after every three months, though he is quick to point out that goats are resistant to disease making them affordable.

“I spend about Sh1,000 per day in buying hay, Boma Rhodes grass and lucerne for my entire brood, which is little money when compared to the income I get.”

He also feeds the goats dairy meal, with mature ones consuming a kilo a day while the kids half.

“There is huge demand for goat milk especially among people living with diabetes and HIV/Aids. I could not have sustained it if I had not embraced synchronised breeding.”

As a commercial farmer, Wathobio grapples with several challenges, among them lack of storage facility. He markets his produce through Facebook, word of mouth and his customers refer others to him.

“Some customers require a litre of milk a day and they are as far as Mombasa Road, about 30km away, this poses challenges.”