Cage aquaculture offers fresh hope to marine fish farmers

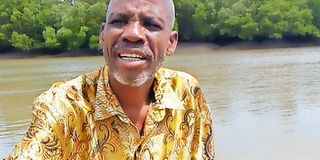

Juma Mashanga at the site of their cage fish farming enterprise in Kwale. according to him, they started it to reverse a decline in fish production attributed to over-fishing, illegal fishing gear and fishing in breeding grounds by the fishers. PHOTO | FADHILI FREDRICK | NMG

What you need to know:

- Community Touch Kenya, a community-based organisation, is behind the introduction of the form of aquaculture.

- The project’s performance has been lacklustre due to low production of fingerlings.

- Apart from the fingerlings production, Mashanga says they can as well use the cages for fish production and fattening purposes.

- Through cage fishing, people will be able to get farm fish in a sustainable way.

Tsunza village in Kwale County is home to various aquatic resources that include different kinds of fish and sea creatures.

As expected, fishing is the mainstay of the area and the economic activity is mainly artisanal, subsistence or inshore.

However, this is changing following the introduction of cage fish farming that is slowly having a huge impact on the community, as it slowly turns fishers into fish farmers.

Community Touch Kenya, a community-based organisation, is behind the introduction of the form of aquaculture.

Juma Mashanga, the coordinator of the project, says they started it to reverse a decline in fish production attributed to over-fishing, illegal fishing gear and fishing in breeding grounds by the fishers.

“We want to teach the locals to be fish farmers so that they can know how to grow fish and not only to fish from the Indian Ocean,” he says of the project situated at Mwache creek of the Indian Ocean at Maguzoni.

Initially, they started with eight ponds measuring 30 by 20 metres, each with a holding capacity of 1,500 to 2,000 fingerlings, following support from the Europe Union.

However, the project’s performance has been lacklustre due to low production of fingerlings.

Lady Luck struck again when the group got Sh4.8 million funding from the Indian Ocean Commission, which they have now used to put up the cage ponds.

"We made the floating cage to help in production of fingerlings to serve the eight ponds as well as to enhance learning," says Mashanga.

The floating cage has four units with nets mounted to house the fingerlings of prawns and milkfish available along the Mwache creek.

DEVELOPMENT OF MARICULTURE

Each of the units measures 2 by 2 metres can accommodate 2,000 fingerlings.

“We used simple materials such as plastic drums that act as wave breakers, wire mesh, nets and anchors to construct the cage, where we put the fingerlings to protect them from predators and offer them artificial feeds and harvest them only when they mature,” he offers.

Apart from the fingerlings production, Mashanga says they can as well use the cages for fish production and fattening purposes.

"We can directly do mariculture besides fingerling production from the cages which provide all natural conditions necessary for the growth of the fish as compared to the ponds."

He is optimistic that through cage fishing, people will be able to get farm fish in a sustainable way.

Dr David Mirera, the assistant director mariculture at Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), says rearing prawns and milkfish fingerlings in cages in the sea is key for the development of mariculture.

“We have a lot of space in the sea that lies idle and the only way to grow mariculture and reproduce is to have cages,” he says.

According to him, growing fingerlings under the cage system helps the fish live in their natural conditions s compared to pond system.

However, he cautions farmers to protect the areas where they have cages to avoid conflicts with the fishers who have been utilising the open spaces for fishing.