Move aside maize, we are keeping silkworms

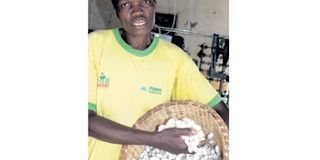

Left: Mulberry plants which silkworms feed on. Emily Bunoro, a member of Iguhu silkworm group, with processed silk produced from the worms. PHOTO | ISAAC WALE

What you need to know:

- The farming is not a common practice in Kenya, but those who are keeping the worms like Elizabeth find it profitable.

- Secretary Charles Otieno says one can make over Sh3,000 from a kilo of silk thread. “Rearing silkworms on half an acre gives us 15kg in every harvest, which gives us good money,” he sais.

As some farmers in Kakamega County labour to grow maize and beans, Elizabeth Khamati is not interested in the crops.

She is a silkworm farmer, an activity that has given her great joy and money as compared to planting maize and beans.

“Silkworms are feeding and clothing my family. I entirely depend on them for a living,” says the 49-year-old mother of four, who is part of Iguhu Silkworm Rearing Group in Ikolomani Constituency.

“Silkworm farming is a good business. I think everyone should do it because we all need clothes.”

Silkworm farming is known as sericulture. The worms are the larvae of a moth called Bombyx Mori. The worms spin a fine, strong, lustrous fibre, which is the primary source of commercial silk.

The farming is not a common practice in Kenya, but those who are keeping the worms like Elizabeth find it profitable.

Elizabeth and her colleagues embraced silk farming after learning it from Kenya Agricultural Productivity Programme officers in 2011, who toured the region to teach farmers of alternative agribusiness ventures.

“We embraced the venture because it needed minimal capital. For instance, I bought 10,000 worms for Sh500 from International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (Icipe).

She also bought mulberry plants from Shinyalu in the county. The rest of the group members joined her.

A male and female moth mate and they later produce at least 500 eggs, which take about 10 days to hatch. The female dies immediately after hatching and the male too follows.

After the eggs hatch revealing little caterpillars, farmers put them under a layer of gauze (a handful of twigs can be used) and feed them on huge amounts of chopped mulberry leaves.

At this point, the caterpillars start vomiting silk threads from tiny holes in their jaws, which they use to spin into their cocoons and completely cover themselves.

This process takes about 72 hours, during which they can produce between 500 to 1,200 silk threads.

“Once this is complete. We then extract the silk by dropping the eggs in warm water. This will kill the insects inside the cocoon,” explains Emily Bunoro, a member of Iguhu group.

If the cocoons are left for 10 to 12 days, the caterpillars inside them turn into winged moths. “This is why you should put some cocoons aside so that you can keep harvesting silk after the hatched moths reproduce.”

One can place the eggs from the second group of moths on a sheet of paper or a cloth until they hatch and keep repeating the process forever.

Not far from Kakamega County is Kabondo Silk Farmers Project Group, which is also engaging in the venture.

Secretary Charles Otieno says one can make over Sh3,000 from a kilo of silk thread. “Rearing silkworms on half an acre gives us 15kg in every harvest, which gives us good money,” he sais.

Kabondo silk project member Emily Ogwendo says 2,000 worms can thrive on a half an acre.

“The worms only feed on mulberry plants,” she says, adding that mulberry seedlings can be acquired from the National Sericulture Station for Sh3 each. Icipe also sells them at Sh2,500.

Once one acquires mulberry plants, one would only be buying caterpillars because the crop grows like a weed and can be used for up to 15 years.

“Kari buys the silk at Sh3,500 per kilo. Currently, we process it at a factory in Kakamega, which the World Bank helped us set up before selling to Kari,” says Elizabeth.

Growing silkworms comes with various challenges.

Elizabeth says some people associate it with witchcraft. But that’s not the biggest problem. “Silk farming is a backbreaking job and often the whole family is required to pitch in for some labour. Activities like mulberry garden management, leaf harvesting, special houses and reeling of silk from the cocoon are taxing, but the good thing is that it is profitable.”

Suresh Raina, Head of Commercial Insect Programme at Icipe, says the sericulture industry is in its infancy.

He notes making the sector have clear and practical goals such as what kind of demand, quality, price and volume of cocoons and raw silk needed requires strong national leadership through administrative, financial, and technical support.

“Icipe has proposed and demonstrated a marketing strategy for sericulture-based products and the problems in the marketing of the products have been identified. A marketing strategy for farmers is being developed and will include the identification of relevant market linkages with private traders,” he says.

“In order to establish and promote a new sericulture industry, there’s need to put into consideration conditions such as electricity, water, capital and market.”