Pastoralists adopt new livelihoods

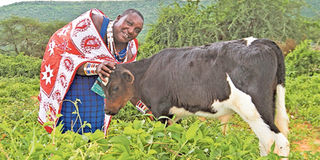

Malelo Ipani with a calf in her homestead in Kajiado County. The 42-year-old community leader is the chairlady of Osupuko Women Group, an association of 50 local women whose families keep lean stocks of dairy cattle that graze in paddocks around homesteads. PHOTO | PIUS MAUNDU | NMG

What you need to know:

- Members of the group do not move with their cattle from one place to the other as has been the tradition. Instead, their families keep lean stocks that graze in paddocks around homesteads.

- The cow produces 24 litres of milk daily on average. Buoyed by her success, she plans to acquire three more Freisian cows.

- A team of lecturers has been working with farmers to identify alternative sources of income in the project dubbed A Sustainable Approach to Livelihood Improvement (ASALI).

- After the training on alternative sources of livelihood, it is up to the farmers to decide what to pursue. The lecturers then offer free extension services and general advisory on farming and pastoralism.

A drive along the Kitengela-Namanga road in Kajiado County reveals an idyllic countryside dotted with fields hosting many head of cattle and greenhouses.

In this neighbourhood, Malelo Ipani’s ranch and homestead stands out from the rest in many ways.

The 42-year-old community leader is the chairlady of Osupuko Women Group, an association of 50 local women who are in the business of bee keeping, buying, fattening and selling steers, and making and selling ornamental beads jewellery.

Members of the group do not move with their cattle from one place to the other as has been the tradition. Instead, their families keep lean stocks that graze in paddocks around homesteads.

Malelo has gone a notch higher and replaced all her 20 indigenous cattle with a single Freshian cow. Her face lights up as she explains why she does not regret the move.

“The Freisian cow is easier to manage compared to the 20 indigenous cattle that I owned initially. They required more attention and a bigger tract of grazing land,” she says, adding that the animal is more valuable.

The cow, which Malelo bought at Sh150,000, grazes on a fenced and paddocked land with lush guinea, horsetail, creeping and foxtail grass.

The cow produces 24 litres of milk daily on average. Buoyed by her success, she plans to acquire three more Freisian cows.

Already, her initiative has inspired five group members to buy their own dairy cows to boost their milk production.

Scores look up to Malelo, whom they see as a beacon of hope in a region grappling with prolonged droughts, floods, disease outbreaks, reduced agriculture production, and other vagaries of climate change.

The subdivision of the sprawling 150,000-acre Elangatawas Group Ranch following a government directive has further complicated things for the herders.

CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS

More than 500 homesteads own parcels of land after the ranch was subdivided five years ago, meaning there is no communal ranch anymore.

Herders either have to drive their animals to as far as Tanzania in search of pasture or watch their animals die.

This has drawn the attention of South Eastern Kenya University (Seku), which has been studying ways in which farmers and pastoralist communities in Kajiado, Kitui and Machakos counties can sustainably leverage natural resources in the wake of multiple risks posed by climate change.

A team of lecturers has been working with farmers to identify alternative sources of income in the project dubbed A Sustainable Approach to Livelihood Improvement (ASALI).

“Multiple studies show that the biggest challenge facing farmers is lack of information on how to farm well in the wake of climate change risks such as drought and floods.

There is need for farmers and pastoralists to diversify their sources of income to reduce their vulnerability to the drastic changes in climate,” says Dr Moses Mwangi, a hydrology and aquatic sciences expert and the lead Seku lecturer working with farmers in Kajiado County.

The use of hybrid seeds, growing high value crops through micro irrigation supported by earth dams and farm ponds, and agroforestry are some of the alternative livelihoods mooted as suitable for these communities. Rainwater and dew harvesting have also been promoted.

“Farmers should also strive to invest in off-farm livelihoods such as running a shop,” notes Dr Charles Ndung’u, a climate change adaptation expert.

After the training on alternative sources of livelihood, it is up to the farmers to decide what to pursue. The lecturers then offer free extension services and general advisory on farming and pastoralism.

Most of Malelo’s neighbours have reduced their herds. The rest are experimenting with mixed farming.

Mr Peter Loontasati, for example, has cut a niche for himself in pasture production and preservation and made some income selling hay and leasing sections of his land to Somali camel herders all year round.