Stevia not so sweet to farmers’ pockets

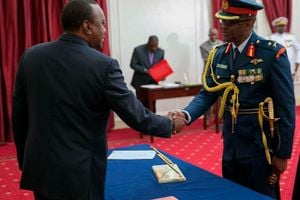

Kibet Tanui in his farm where he uprooted stevia and replanted tea. PETER KAMAU |

What you need to know:

- With tea prices plummeting, many farmers would visit the farm that hosted stevia and is owned by Kibet Tanui hoping to get some education so that they can join him.

- “I was among the first farmers who registered to grow the crop in 2011. I was excited about the prospects in stevia because tea was not fetching good prices. About 400 of us registered to grow stevia but only 60 made it.”

- He blames middlemen for distortion of the market, adding they could be responsible for some of the allegations made against the firm.

The quarter-acre farm in the middle of expansive tea estates in Kabianga, Kericho was once an envy of many.

With tea prices plummeting, many farmers would visit the farm that hosted stevia and is owned by Kibet Tanui hoping to get some education so that they can join him.

On the surface, Tanui, who grew the stevia crop, appeared to be doing well.

However, the farmer, who also grows tea, is among 60 in the area who faced numerous challenges that made some uproot the crop. Tanui is among those who uprooted.

“We had been promised good returns from stevia but this was not forthcoming. It is over a year since I uprooted the crop and went back to tea.”

Tanui embraced stevia after being told of a company that was introducing the cash crop in the region.

“I was among the first farmers who registered to grow the crop in 2011. I was excited about the prospects in stevia because tea was not fetching good prices. About 400 of us registered to grow stevia but only 60 made it.”

Five years later, Tanui says prices remain low and the company has not fulfilled many promises to farmers it had contracted to grow the crop for export.

“The company did not offer the Sh200 per kilo of dry leaf we had been promised for our produce. Second, it stopped offering technical support to us and third, some of the inputs that we were promised such as lime to improve the soil for stevia production were not provided,” adds Tanui.

David Chirchir, his neighbour, planted 12,000 seedlings initially but he has reduced them to only 4,000 plants. He notes that the crop is labour-intensive but it is not prone to pests and diseases, thus, making it cheaper to grow.

However, the main problem with stevia is the low price offered by the company, which is the sole buyer.

“When we signed the contracts with the company, we were told the only deduction they would make from our earnings was 30 per cent to cater for inputs such as fertiliser and polyethylene material for nursery sheds,” he recounts, adding they later discovered the deductions were many.

Samuel Bengat, another stevia farmer is also contemplating abandoning the crop.

“If they can pay better prices for stevia, then it would make business sense to grow it, but at the current price of Sh105 a kilo, no farmer can grow stevia and make a profit,” says Bengat.

EARNINGLY POORLY

The general manager of the company refutes claims that farmers are earning poorly. He says that since the company entered the Kenyan market, there has not been any downward revision of prices.

He says they started paying farmers Sh70 per kilo in 2011 but it has since increased to Sh105, which will further be raised to Sh140 soon.

He adds that their role was not to supply farmers with inputs but to advice them.

“I think farmers who are uprooting stevia are just poor managers of their crops. Stevia requires good management to give good returns. Most farmers have shown poor weed management and even fertiliser application, hence they end up with poor yields and less income,” he adds.

He explains that there are no unjustified deductions on farmers’ payments, noting that they only charge for inputs supplied on credit such as polyethylene sheds, seedlings and fertiliser, which are deducted at the rate of 30 per cent of the value of delivery.

He blames middlemen for distortion of the market, adding they could be responsible for some of the allegations made against the firm.

Paul Mwangi, a farmer from Kangawa village in Molo too has not had good experience with stevia.

He says farmers in his village were introduced to stevia production by the Network for Eco-farming in Africa, which supplied them seedlings.

“The organisation was buying a kilo of dry leaf at Sh200 but they stopped. So we had to sign new production contracts with another company. Many farmers have, thus, abandoned stevia production. From the 11 who were growing stevia here, only four of us have the crop now,” he says.

Stevia (stevia rebaudiana bertoni) is a natural sweetener, which belongs to the family compositae.

Stevia leaves have a long history of use as sweeteners, due to the presence of sweet crystalline glycosides called steviosides, which are 200 to 300 times sweeter than sucrose.

Stevia is propagated from seeds planted in trays placed in nurseries or greenhouse for a period of seven to eight weeks then transplanted to the main field. The plant grows well at an altitude of 1,200m above sea level and in soils rich in organic matter.