Journey towards less toxic cancer tools

Some cancers, such as brain cancer remain on the margins of these new treatments. PHOTO| FILE.

Chemotherapy has been used for decades to kill tumours, but it is toxic and attacks healthy cells, leading to major side effects like weakness, pain, diarrhoea, nausea and hair and weight loss.

The other dominant cancer treatment is radiation.

In recent years, however, a series of clinical trials have shown that it is possible to better treat and even cure some of the most difficult forms of cancer without resorting to the most toxic techniques.

For example, in the case of breast cancer, a major study published in early June at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference showed that for tens of thousands of women, surgery and hormone therapy were enough to keep cancer away.

In a finding that surprised the cancer community, researchers found that chemotherapy was being given unnecessarily.

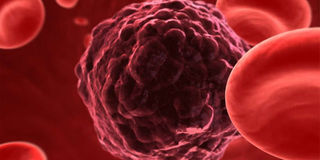

One of the treatments that holds promise is immunotherapy. It trains the body’s natural defences — immune cells, also known as T-cells — to detect and kill cancer cells, which otherwise can adapt and hide Some experts are cautious, having been disappointed numerous times by other new-fangled approaches to fighting cancer.

But many consider immunotherapy a turning point. More than 30 immunotherapy drugs are in development, and 800 clinical trials are underway, according to Otis Brawley, medical director of the American Cancer Society.

Genetic analyses are also becoming ever more common for tumours, allowing more precise and rapid treatments for patients. Johns Hopkins University in the US has a genomic lab designed to help doctors personalise patient treatments, rather than basing treatment simply on the location of the tumour.

"We have better and better tools to say, ‘Yes, he needs to be treated, you don’t," says William Nelson, director of the Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

Immunotherapy and other personalised treatments are making progress on leukaemia, breast, lung, cervical, colon and rectal cancer. However, some cancers, such as brain cancer remain on the margins of these new treatments.

Oncologist Julie Brahmer hopes that one day, metastatic cancers — those that can spread to points distant from the site of origin — will be treated like a “chronic disease,” rather than a death sentence.

Already, doctors are intrigued by the unusually long remissions – more than the typical one-year-and-a-half to two years – seen in a small number of patients; these success stories make up about 10 to 15 per cent of patients.