WHO calls for urgent action to end tuberculosis infection

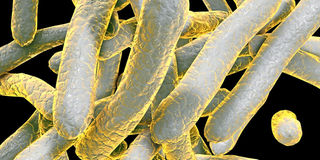

Bacteria which cause tuberculosis Mycobacterium tuberculosis, 3D illustration. ILLUSTRATION| FILE

The World Health Organisation has called for increased domestic and international funding to end tuberculosis by 2030.

In the 2018 Global TB Report released last Tuesday, the global health body said that fewer people fell ill and died from the highly infectious disease last year, with global efforts having averted an estimated 54 million deaths since 2000. However, the WHO warns that countries are still not doing enough to end the disease, as TB remains the world’s deadliest infectious disease.

The report urges political leaders gathering this week for the first-ever United Nations High Level Meeting on TB to take decisive action. Nearly 5o heads of state and government are expected to attend.

In Kenya, where tuberculosis is the fourth leading cause of death, after a dramatic decline in TB deaths from roughly 10,000 in 2015 to 4,735 in 2016, there was a resurgence in 2017 with 9,081 deaths, according to the Economic Survey 2018. In 2017, Kenya reported and treated 85,188 TB patients, among them 7,771 children, making it one of the countries with the highest burden of the disease.

While launching the first Tuberculosis Patient Cost Survey in July, Cabinet Secretary for Health Sicily Kariuki, said there are plans to include TB treatment in the National Hospital Insurance Fund benefit package, as a way of funding treatment locally. The Ministry of Health has been rooting for implementation of appropriate and affordable primary healthcare interventions that will help end TB.

ADHERENCE TO TREATMENT

Ms Kariuki said that affected households would be linked to existing social protection and food security programmes. This is because although TB diagnosis and treatment is free, nutrition, transport and other costs associated with seeking and receiving healthcare and the related loss of income may worsen poverty and health.

“Such costs make TB patients less likely to present for care, complete TB testing and initiate and adhere to treatment. They place an economic burden on households, worsening poverty and increasing deaths due to the disease,” she said. Providing safety nets can cushion patients against the direct costs they incur while seeking treatment. The Ministry of Health also undertook to improve TB sample referral mechanisms and ensure the availability of free diagnostic and treatment services. The study revealed that patients with drug-resistant TB spend an average of Sh145,109 during treatment, while those with drug-sensitive TB incur Sh25,874 in direct and indirect costs. Moreover, 63 per cent of patients with drug-resistant TB lost their jobs due to the disease. All these factors undermine treatment and efforts to curb the spread of disease.

In the Global TB Report, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the world must capitalise on the new momentum and act together to end the terrible disease.

“The WHO report provides an overview of the status of the epidemic and the challenges and opportunities countries face in responding to it,” he said, adding that ending the epidemic requires action beyond the health sector, to address the risk factors and determinants of disease. Globally, TB deaths have decreased over the past year. In 2017, an estimated 10 million people were diagnosed with tuberculosis, and 1.6 million (including 300,000 HIV-positive patients) died. Since 2000, a 44 percent reduction in TB deaths occurred among people with HIV compared with a 29 per cent decrease among those who were HIV-negative. Faster reductions in new cases have occurred in Europe (five per cent per year) and Africa (four per cent per year) between 2013 and 2017. Some countries are moving faster than others – as seen in Southern Africa, with annual declines in new cases of four per cent to eight per cent in countries such as Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Drug-resistant TB remains a global public health crisis: In 2017, over half a million people were estimated to have developed disease that was resistant to rifampicin – the most effective first-line TB drug. The vast majority of these people had multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), that is, combined resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid (another key first-line TB medicine).