We’re unprepared to handle acute myeloid leukaemia

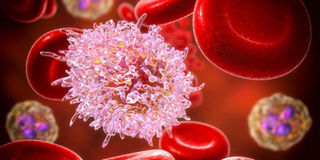

AML occurs when the bone marrow, the factory that produces all blood cells, ceases to work properly. PHOTO | FOTOSEARCH

Blood and bone marrow (haematological) cancers are rare, contributing only to approximately five to 10 per cent of all cancers.

Acute myeloid leukaemia, or AML, one of about a dozen existing haematological cancers, if untreated, results in death within weeks to months from infection, bleeding, or the effects of severe anaemia on vital organs.

The leukaemias are rare, constituting approximately three per cent of all cancers, and AML one per cent. It is estimated there were approximately 33,000 deaths from cancer in Kenya in 2018, with approximately 3,200 due to blood cancers and 1,300 (leukaemia).

This latter figure is likely to be an underestimate, since a number of patients with acute leukaemia die at home or in hospital before receiving an accurate diagnosis or proper treatment.

AML occurs when the bone marrow, the factory that produces all blood cells, ceases to work properly. Instead of the normal production and development of white cells (which fight infection), red cells (which transport energy around the body) and platelets (which protect from abnormal bleeding), a rogue ‘seedling cell’, or stem cell, which has failed to develop into a functional blood cell, multiplies in large numbers, and while still in an immature state, fills out the bone marrow, eventually spilling over into the blood.

These abnormal cells eventually phase out the normal cellular components of the bone marrow and blood (white cells, red cells and platelets), and when that happens, the patient will experience symptoms such as tiredness and weakness, recurrent infections due to marked reduction of white blood cells, and bleeding or unexplained bruising due to lower number of platelets.

COMPLEX DISORDER

The actual cause of AML is unknown in a vast majority of cases. The classical textbook risk factors do not appear to be a prominent feature of the disease in the patients in Kenya.

What we do know, however, is that there are a number of steps or ‘accidents’ that occur at the molecular level in these cells which eventually lead to the development of AML.

These molecular accidents, acting synergistically with each other, result in a complex disorder that is far greater than the sum of all the molecular events. It is this intricate interaction between these molecular events that ensures that no two cases of AML are identical to each other, and can result in an illness difficult to treat and cure.

Fewer than five institutions in Kenya provide services, which can successfully support patients with AML through this intensive treatment. It is recognised worldwide that access to comprehensive transfusion services and close patient support in dedicated haematology units or wards has been a major contributory factor towards improved outcomes in patients with AML over the last 40 years.

Our reality is that many patients with AML do not receive treatment for their illness because of lack of access to resources. Additionally, in some of our institutions, there is a high rate of death because of lack of supportive services after chemotherapy has been administered. It goes without saying, then, that there is an urgent need to have a robust national transfusion service and to develop dedicated treatment units managed by appropriately trained medical and nursing staff.

It is clear that in AML, unlike other haematological cancers, the use of targeted therapies is not enough to eradicate or control the disease. It is the desire that correct incorporation of targeted therapies into traditional treatment regimens will result in better outcomes even for patients presenting with a disease that is very difficult to treat from the onset.

Dr Mwirigi is a consultant haemato-oncologist at Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi