Agency approves monthly vaginal ring as new HIV prevention method

What you need to know:

- The dapivirine vaginal ring intended to be used for a month at a time has moved one step closer to potentially becoming a new HIV prevention.

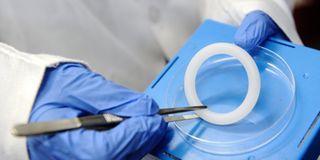

- The ring, which women can insert and replace themselves, slowly releases an antiretroviral (ARV) drug called dapivirine into the vagina, the potential site of HIV infection - during the month it is worn, over a period of 28 days.

- If approved, the dapivirine ring would be the first biomedical prevention method specifically for cisgender women and the first long-acting method.

A silicone vaginal ring containing antiretroviral drug dapivirine has received an agency's approval as a new HIV prevention method for women.

The dapivirine vaginal ring, intended to be used for a month at a time, has therefore moved one step closer to potentially becoming an official HIV prevention method.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) announced Friday that it had adopted a positive scientific opinion on the ring's use in low- and middle-income countries, following a study which proved it can reduce the risk of type 1 (HIV-1), a virus that causes the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The ring is seen as a method for cisgender women (a term for people whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite being the face of the epidemic, they have few options for protecting themselves against getting infected.

This is the eleventh medicine recommended by EMA under EU Medicines for all (EU-M4All), a mechanism that allows the EMA’s human medicines committee to assess and give opinions on medicines intended for use in countries outside the European Union under Article 58 of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004.

USE

The ring, which women can insert and replace themselves, slowly releases an antiretroviral (ARV) drug called dapivirine into the vagina, the potential site of HIV infection - during the month it is worn, over a period of 28 days. It was developed by International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), a US-based non-profit product development partnership.

“The EMA’s opinion is a significant step forward for women, who urgently need and deserve new, discreet options to manage their HIV risk on their own terms,” said Dr Zeda Rosenberg, IPM’s founding chief executive and the product’s regulatory sponsor.

She added: “As we celebrate today’s news with the many partners around the world involved in the ring’s development, we also look ahead to the collective effort still needed to obtain country approvals to make the ring available to women in sub-Saharan Africa.”

REGULATORY AUTHORITIES

Following Friday’s announcement, IPM plans to submit applications to national medical regulatory authorities in east and southern Africa, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), and to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) later this year.

"This has been a long road, and by no means have we reached our ultimate goal of having multiple options for women at risk of HIV, but this positive opinion by the EMA gets us closer than we have ever been,” said Sharon Hillier, a professor and vice-chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

She is also the principal investigator of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Microbicide Trials Network (MTN).

She added, “It is a monumental achievement for women's HIV prevention, and to that, we owe IPM for its scientific leadership and vision, and steadfast advocacy.”

WOMEN VULNERABLE

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), at the end of 2019, there were 38 million people living with HIV worldwide.

While there is no cure for HIV infection, antiretroviral medicines can control the virus and help prevent transmission. In some parts of the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, women are especially vulnerable to being exposed to HIV because they cannot negotiate safer sex for a variety of reasons, such as cultural, social and gender barriers, which put them at a heightened risk of unintended pregnancies, STIs and HIV.

A number of HIV prevention strategies are available, including the use of protective methods during sexual encounters and PrEP.

People who do not have HIV and are exposed to the virus can take PrEP medicines daily to reduce their risk of getting infected.

Dapivirine reduces the risk of HIV-1 infection after 24 hours of ring insertion. In order to maintain efficacy, a new ring is to be inserted immediately after the previous one is removed.

SAFETY

The safety and efficacy of the dapivirine ring were studied in a randomised clinical study in which 1,959 women were assigned to either the ring or a placebo.

The ring achieved a reduction in the development of HIV-1 antibodies (i.e. seroconversion), which is a measure for the presence of HIV in the body, of 35 per cent compared to the placebo group.

The EU’s human medicines committee is looking for further safety and efficacy data in younger women (18 to 25 years old) and on resistance testing in women who become HIV positive (seroconverters).

The most commonly reported adverse events for the ring were infection of the structures that carry urine, vaginal discharge and itching of the vulva and the vagina.

In a parallel, the WHO is expected to revise its HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention guidelines with evidence-based recommendations for policymakers and healthcare providers on the ring's use.

It is also expected to make a determination for "prequalification," a global quality assurance designation.

Other than condoms, the only other HIV prevention product approved so far involves daily use of an ARV pill, an approach called oral pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.

If approved, the dapivirine ring would be the first biomedical prevention method specifically for cisgender women and the first long-acting method.

Importantly, it would mean women could choose the method that works best for them.