Fighting cervical cancer with hand-held device

What you need to know:

- Thermo-coagulator burns abnormal cells in the cervix, seen as a game-changer with new cases hitting 5,250 each year.

Mercy Wanjiru is a lucky Kenyan woman. She had never had unusual vaginal discharge to signal abnormalities in her cervix, but a friend persuaded her to go for a free gynaecological screening in Nairobi’s low-income Kayole neighbourhood.

“The test showed that I had three abnormal cells in my cervix. I was so shocked. I knew that I was staring at death and feared that my two-year-old would grow up without a mother,” says the 25-year-old.

Abnormal cells, known as pre-cancer lesions, eventually grow into cancer. In a country where a few women go for screening and seek early treatment, many are diagnosed in late stages with the hard-to-cure invasive disease.

But Ms Wanjiru received a same-day treatment, which takes less than a minute, in a makeshift medical camp, giving her a new lease of life. The relatively new technology, thermo-coagulation which burns abnormal cells in the cervix, is seen as game changer in taming new cervical cancer cases which have risen to 5,250 each year in Kenya, according to World Health Organisation (WHO).

For Kenyan women, a positive cervical cancer screening is unsettling.

The lack of awareness that lesions in the cervix are easily cured and cancer prevented, the long delays in public hospitals, the shortage of doctors and the high cost mean that thousands feel lost after they are found with abnormal cells.

Kenya’s expensive cancer treatment history has prompted the use of low-cost technologies such as thermo-coagulation where a hand-held device is used to burn abnormal cells in the cervix, stopping them from developing into cancer.

Dr Nicholas Kisilu of Ampath Oncology Institute in Eldoret says thermo-coagulation is not yet common in Kenya, yet it is best positioned to slow down cervical cancer rates, as patients are screened and treated immediately.

“I have only treated 20 women. This technology will tremendously reduce the number of cervical cancer cases we see due to delayed treatment. With the efficacy comparable to cryotherapy in the Western countries, my guess is that soon it will replace the cryotherapy use,” Dr Kisilu says.

One advantage of thermo-coagulation is that the device is portable.

“The device is the size of a laptop which can be carried anywhere. It is easy to use that one does not need a gynaecologist as nurses at screening clinics can easily and safely use it,” he said.

Africa Cancer Foundation (ACF), a Kenyan charity, has teamed up with Canadian firm Bridge to Health Medical and Dental, to use thermo-coagulation.

“We have treated 30 women in Kisumu, Nairobi, West Pokot, Nyandarua and Makueni since February last year,” says Wairimu Mwaura who is in charge of ACF Programmes.

ACF, which has been screening for different cancers free for eight years now, says having a thermo-coagulator on site ensures there is no loss on follow up of the women after diagnosis.

A Thermocoagulator used in treating pre-cancer cervical lesions. PHOTO | COURTESY

Previously, some women would return to distant areas where they live or work after screening, making it hard to trace them if their tests showed they had precancerous lesions.

Dr Kisilu is among the doctors who treat patients in mass screenings in Kenya in partnership with ACF because Ampath cannot afford its own thermo-coagulator.

Research shows that in most countries, up to 80 percent of women diagnosed with cervical pre-cancer never receive treatment. Current treatment methods are often expensive and difficult to reach the poor in rural areas, underserved by specialised doctors.

At present, the standard treatment of most precancerous lesions is gas-based cryotherapy, which involves freezing a section of the cervix to destroy abnormal cells, which then shed off after weeks.

However, most times public hospitals run out of gas, or some procure a type that contains impurities, making it ineffective.

Other hospitals use loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), which involves scraping off the diseased tissue using a wire loop. In most cases, the treatment is unavailable due to lack of experts.

“With thermo-coagulation, you treat the patient immediately after diagnosis. The device is simple to use and easily portable to remotest of places as long as the batteries are charged. The treatment method is painless, fast, requires no anaesthesia, and is administered within a very short treatment cycle, less than a minute,” said Ms Mwaura.

In terms of costs, Dr Kisilu adds that thermo-coagulation is cost-effective compared to cryotherapy.

“It is cheaper compared to cryotherapy because there is no need for gas cylinders and refilling costs. The gas cylinders are also bulky to keep. It is also cost effective when dealing with large numbers and it has the same efficacy as cryotherapy,” he said.

Thermo-coagulation uses heat to destroy tissue in the cervix. A speculum and acetic acid are inserted through the vagina to define the lesion in the cervix.

“A probe is introduced through the speculum and focused on the lesion for 20 to 30 seconds. This is repeated until the whole lesion is covered. The probe is removed and a doctor checks for any signs of bleeding and then removes the speculum,” said Dr Kisilu, who has used the device for one and half years.

SHAME, CULTURE

Even with the availability of the technology in mass screening sites, the turnout for gynaecological check-ups is still low due to shame and culture. For instance, in the eight years that ACF has been doing free screenings and treatment in various counties, only 20,000 women aged between 25 and 49 have gone for screening.

“Ten percent of those we found to have precancerous lesions or advanced cancer,” said Ms Mwaura.

Because rural areas lack high-quality labs, and the results can take weeks to arrive, ACF uses a cheap vinegar method to screen for cervical cancer.

A health worker brushes vinegar on the cervix. It makes precancerous spots turn white.

Even those who can afford regular Pap smears or HPV tests, the turnout is low.

According Pathologist Lancet Kenya, one of the biggest laboratories in the region, they do about 10,000 Pap smears and 1,000 HPV tests every year.

Of those tested, about 17 percent are found to have high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer.

“High-risk HPV is more prevalent in younger women in their early 40s,” said Dr Ahmed Kalebi, the chief consultant pathologist and CEO of Pathologist Lancet Kenya, during a Kenya Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society conference in Diani on the Kenyan coast.

From the Pathologist Lancet statistics, a majority of the woman who go for screening are aged between 21 and 60.

HUSBAND PERMISSION

Another challenge is gender power relations in Kenya, which clouds screening and treatment of cancers of the reproductive organs.

Most women are hesitant to go for pelvic exams and if found with abnormalities, they can only be treated if their husbands consent, yet the burden of cancer is heavier on women than men.

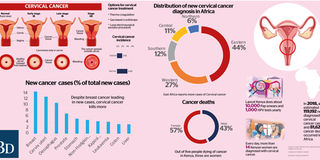

Women lead in cancer deaths with 18,772 dying from the different types compared to 14,215 men yearly, representing 56 percent of the total deaths, according to World Health Organisation (WHO).

Cervical cancer is the leading cancer killer in women in Kenya, with an estimated 3,286 deaths each year.

“Some women decline the treatment, fearing that their husbands will refuse to abstain from sex afterwards. After treatment of precancerous lesions of the cervix with thermo-coagulation, a patient should abstain from sex for 30 days until they are healed,” Ms Mwaura said, adding that some patients are also in denial when they are told of the diagnosis and walk away, never to return.

Before Ms Wanjiru was treated using thermo-coagulation, she was asked to come with her husband.

“He had to give consent because I couldn’t have gone ahead with the treatment then he refuses to abstain from sex for a month. He didn’t know much about the treatment but when he heard that the abnormality would multiply and become cervical cancer, he agreed quickly. The chances of surviving cancer especially if you live in low-income neighbourhoods like ours is very low,” says the mother-of-one.

Some men decline and the women are referred to health facilities for other forms of treatment.

Myths that thermo-coagulation causes infertility or it will not rid the cervix of the lesions also inhibit the take-up.

However, studies show that treatment of cervical precancerous lesions prevents up to 80 percent of cervical cancers in high resource countries where screening is routine.

“It is associated with premature deliveries in pregnant women but this is very rare, less than five percent,” Dr Kisilu said, adding that after treatment, a patient is required to follow up tests after six months to one year.

SIDE EFFECTS

A patient may experience side effects such as pain, bleeding and an infection, although these occur rarely.

Six months later, Ms Wanjiru said she returned to a public clinic for a Pap smear.

“I was anxious that the treatment may have not worked, I went for three screenings. The three abnormal cells have cleared,” she said.

The free screenings and treatment are crucial to people like Ms Wanjiru, who braids hair for a living.

On a good day, she makes about Sh500 and her husband is a mason in a neighbouring estate. With no regular monthly income, she has no time to wait at the jammed public hospitals, and she cannot afford a private doctor.

The prospects that this low-cost technology could save lives of thousands of poor women excites Dr Kisilu, but only if the device which costs about Sh250,000 is available in more hospitals and health workers are trained in how to use it.

PAINLESS TREATMENT

What worries Ms Wanjiru is the number of young women who know nothing about early screening and those who fear going for pelvic check-ups.

“The treatment was painless, just a backache that eased after I took painkillers. I went back to work after a day and resumed my normal chores, including fetching water from a nearby borehole and carrying it up the stairs to my house,” she said.