How Mwalimu Julius Nyerere built state out of disparate nations

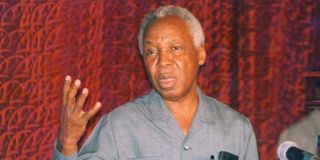

The founding President of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere. ‘Development as Rebellion: A Biography of Julius Nyerere’ is a three-part series that looks at his life. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Britain, the colonial masters, treated Africans as third-rate citizens, below Arabs, Asians and Europeans.

- When Nyerere resigned from teaching to work for Taa, he wasn’t even assured of a salary

African presidents who took power from the colonialists had the difficult task of building the new nations.

Considering that independence for came not so long after the Second World War, several new nation-states got their freedom at a time of economic difficulty. They may have had the political kingdom, but only relatively.

Why? Although there seemed to be unity of purpose in the search for political independence, there were bound to be troubles due to the sheer size of some of the countries, the differences between ethnic communities, and the social class stratification that colonialism had bred.

Tanzania, with more than 100 ethnic communities, different races and religious groups, different stages of urbanisation — ranging from the established coastal cities, somewhat modern trading centres in the interior — to rural communities that had barely been touched by the colonialists, was a challenge to the new leaders.

So, how did Mwalimu Nyerere and his team in the Tanganyika African National Union (Tanu) pull off the near miracle of cobbling together the disparate tribes? How did they mobilise Tanzanians into believing that Tanzania could gain independence as a multiracial, multiethnic, multicultural and multireligious nation-state?

Rebellion

This is the story in volume two of “Development as Rebellion: A Biography of Julius Nyerere” (Mkuki na Nyota, 2020). This volume is titled “Becoming Nationalist,” with the lead author as Ng’wanza Kamata.

It seems that Mwalimu Nyerere had thought through the political question when he chose to join politics from the classroom. By the time he was elected president of Tanganyika African Association (Taa) on July 17, 1953, Mwalimu knew that the political awakening among Africans could be galvanised to bring about political change.

Britain, the colonial masters, treated Africans as third-rate citizens, below Arabs, Asians and Europeans. Racism always breeds discontent and the Africans in the cities and towns of protested this discrimination.

When Nyerere resigned from teaching to work for Taa, he wasn’t even assured of a salary. But he was willing to imperil his family economically for his countrymen and women to gain political freedom.

Mwalimu set aside his intellectual pursuits although one could argue that working for Taa at that time was somewhat intellectually challenging.

Nyerere is depicted as a man on a mission to free Tanganyika from colonial rule. Faced with an obstinate and cunning colonial administration on the one hand and a sometimes fractious party on the other, the writer depicts Mwalimu as playing a delicate balancing act.

Some of his colleagues in Taa and Tanu saw him as soft and too moderate with the colonialists while the administration thought of him as sometimes tending towards the radical.

Yet Mwalimu is presented as astute, sometimes acceding to demands from the colonialists to evaluate the consequences. A case in point is when he accepted nomination to the Legco only to resign four months later, declaring that serving in the Legislative Council would be “cheating the people and cheating my own organisation”.

Public office

This is a Nyerere who refuses to be “bought” with the privileges that came with public office. But “Becoming Nationalist” is really about how Nyerere and his colleagues in Tanu and later Chama cha Mapinduzi deal with the key issues in the struggle against British rule in Tanganyika.

Unlike in Kenya, where the fight against colonialism focused on land alienation and racial prejudice, in Tanganyika the racial policies provided the impetus for mobilisation of Africans against the regime.

But should the struggle for freedom be based on racial division alone? This was a question Nyerere and Tanu had to deal with. Whereas the party belonged to Africans, how would it involve non-Africans in elections?

The race issue would emerge later when Tanu and Nyerere’s government had to deal with the question of citizenship. This subject led to heated debates in the party, with members divided on who should have Tanganyika citizenship – the source of the problem being the whether to grant people of European and Asian descent citizenship.

Also, the army mutiny of 1964 happened because of the racial profile of the leadership structure. Whereas the country had decolonised politically, as Kamata notes, the Tanganyika Rifles “retained not only the colonial ‘pattern of army organisation,’ but also the structure and philosophy of its predecessor, the King’s African Rifles.”

High-ranking officers remained predominantly white, with Africans hardly promoted beyond captain. Nyerere and the government had been slow to “Africanise” the forces and the soldiers were unhappy. But he found a way around the problem.

Even though the political kingdom had been attained, Nyerere had to deal with the question of the economic kingdom after independence. Predictably, the trade unions, which were supporters of Tanu, demanded better working conditions and pay. He needed to develop the country beyond the little that the colonial government had done.

What motivated the Arusha declaration and the Ujamaa philosophy?

Mwalimu’s problems were many, personal and communal; arising from internal party struggles and caused by the colonial government; administrative but also political, yet he sought to resolve them by sometimes calling on close friends and party men and women to intervene on his behalf. Or he would take up the challenge and verbally slog it out with the opposition.

Overall, Nyerere appears to have fully committed himself to pursue the freedom of Tanganyikans from colonialism in all ways possible, at all costs. It is no wonder that Julius Nyerere published six books founded on the idea of “freedom”.

Next week we will look at Book 3 of the biography, Rebellion Without Rebels (Issa G. Shivji). Apologies to Prof Saida Yahya-Othman for the misreference to her in the review of The Making of a Philosopher Ruler)