The new normal: Modernity, culture as strange bedfellows

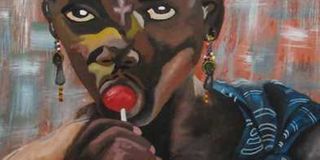

A painting titled ‘Culture Clash’ by Vavick Odhiambo. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Responding spontaneously, a male mourner expressed his surprise that teachers of English were subjecting their children to ‘lies’ or fiction as the girl called them.

- Another male mourner added that it would be a disastrous taboo for the girl to live on her father’s land and not behave ‘properly’ like Akoko.

Can a work of pure fiction be treated as an authoritative reference and source of solutions to burning human issues the same way constitutions or sacred texts are? The answer is yes, because that is what happened to a popular Kenyan novel recently.

A few weeks ago, during post-burial interactions at a home in the countryside, a father had a heated argument with his nubile daughter over the uses and misuses of Margaret Ogola’s The River and the Source in attempting to resolve marital issues relating to land.

The clash erupted when the girl requested that she be allocated her share of her ancestral land.

Perhaps worse still, and an abomination of sorts, a future son-in-law only known to the girl, had been listening to the exchanges, but more on that later.

The unusually small crowd owing to coronavirus restrictions on the size of funeral gatherings, was momentarily shocked and lost for words because such a request was worse than the most sacrilegious.

Inherit property

As a law graduate and, therefore, a “learned friend”, she quickly reminded them that the 2010 Kenya Constitution empowers the girl-child to join the boy-child in inheriting their father’s property including land. She went further to stress that that was the “new normal” in Kenyan culture.

Her very literary father immediately referred to Ogola’s novel, but particularly to the central character, Akoko: “She automatically moves to her husband’s home in a distant clan and does not demand land from her because age-old tradition and practice forbids that.” He recalled buying her the novel as a set book for her Form Four English examinations and thought she would have noted such an impatient event in Akoko’s life.

The girl quickly countered that Ogola’s was a work of fiction and not a statement of the truth about the current realities and practice. She added that her dad was mixing up facts and fictions.

Responding spontaneously, a male mourner expressed his surprise that teachers of English were subjecting their children to ‘lies’ or fiction as the girl called them.

He said she had been misguided in school and emphasised that no married woman is known to have inherited a father’s piece of land since the beginning of the world. His source was the Bible but he did not mention the exact book.

Another male mourner added that it would be a disastrous taboo for the girl to live on her father’s land and not behave ‘properly’ like Akoko. He quipped that in local parlance, she was an ‘ogwang’, a wild-cat that must plunge in to ‘the wild masculine world in search of a husband who will give her a home, away from her clan.

Buried in the wild

If she or Akoko were to die unmarried, they would be buried in the wild, far away from their fathers’ homesteads in order to ward off deadly ghosts mourning deep in to the night for husbands they failed to have in real life.

The last mourner to speak, before her father responded again, observed that having a home next to her male siblings’ was the same as planting termites at the corner posts of a house so that it collapses fast. Which meant that her presence and a home would ruin the prosperity and wellbeing of his brothers otherwise known as the siro or pillars of her father’s home and family. He cited examples without an argument to back his claims.

The girl’s dad was delighted by the crowd’s support and proceeded to attribute the prosperity of Akoko’s children and their offspring to her having settled in a home away from her father’s.

To clinch what he believed was an argument, he zeroed-in on his daughter’s case and argued that her recent graduation from Law school was a direct consequence of her mother’s decision, on the strength of tradition to establish her own space, away from her ancestors.

In a terse response, she termed what was going on “a trial of culture and belief”. The fact that Akoko’s father “seeks her a marital home in a faraway clan is a violent act of ejection and rejection” and was equal to child neglect and abuse. She added that marriage should not and must not mean uprooting a girl-child from the blessings of the habitat and surroundings of her living and dead ancestors.

Vacating father’s home

After concluding that belief cannot thrive on logic in a court of law against her demand for land, she introduced her fiancé. He had travelled from Migori to condole with her on the loss of her paternal grandfather.

A lawyer like her, tradition did not allow him to listen to the conversations that had been going on. Neither she nor the fiancé knew that unwritten law. Nor was he aware that he was not expected to address the crowd before undergoing the formal procedures for crowning him a son-in-law.

Announcing that his father did not have land to share with him and wife-to-be, he proceeded to declare he was looking forward to building a home next to his mother-in-law.

Cheered on by the prospective bride, he stressed that she would not be vacating her father’s home like Akoko because the new normal had long changed the laws and no longer should she be regarded as a wild animal.

Curses and sighs at the abomination of a son-in-law living with his wife next to her mother followed in a torrent as the crowd slunk in to the dusk. Their very negative reaction was an endorsement of Akoko’s gesture and a plus for Ogola’s novel in resolving cultural issues.

Mary Obudho teaches English and Literature at Nyakongo Girls Secondary School, Siaya County.