Why Kiswahili should play a bigger role in Kenyan unity

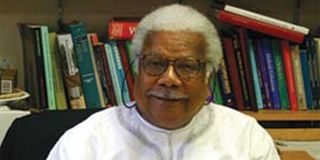

Prof Ali Mazrui, who was a globally acclaimed scholar of history and economics.

What you need to know:

- In Kenya although Kiswahili is an official language alongside English, courtesy of the 2010 Constitution, Kiswahili has been relegated to the periphery.

- Kenya has about 42 languages while Tanzania has more than 100 languages.

The language enables members of different tribes to communicate with each other in various fora.

In October 2005, Africa hosted the Seventh International Conference on Language and Development. The historic meeting, held in Addis Ababa, was unique in two ways.

One, it was the first time a conference of such magnitude was being held in Africa since the series of international conferences on language started in Bangkok, Thailand, in 1993.

Two, the participants – mostly experts on language, education and development, civil society groups and government officials from all over the world – deliberated on the complexities of the language situation in Africa.

The participants observed that most African countries have accorded languages of their former colonial masters dominant roles in national affairs. In Kenya, for example, although Kiswahili is an official language alongside English, courtesy of the 2010 Constitution, Kiswahili has been relegated to the periphery.

Small populations

It was also observed that compared to other parts of the world, African countries have small populations that are made up of very many language groups. Cameroon was cited as an example. Although it has a population of about 12 million people, it has more than 250 languages.

Kenya has about 42 languages while Tanzania has more than 100 languages. Somalia, on the other hand, is homogenous – with only one language.

African scholars have over time interrogated the language situation in the continent. In their books, Swahili State and Society: The Political Economy of an African Language (1995) and The Power of Babel: Language and Governance in the African Experience (1998), Professors Ali Mazrui and Alamin Mazrui argue that some of the strongest and most persistent loyalties in Africa are still ethnic.

They say that ethnic loyalties do not simply disappear, but are gradually absorbed into a wider network of allegiances.

Ethnic loyalties

The picture of ethnic loyalties in African politics is well captured by Ali Mazrui’s illustration in his essay titled ‘If African Politics are Ethnic Prone, Can African Constitutions Be Ethnic Proof?’ In the essay, Mazrui gives a good example of ethnic loyalties using the late Oginga Odinga and the late Obafemi Awolowo of Nigeria.

He says: “One major characteristic of politics in post-colonial Africa is that politics are ethnic prone. In his efforts to convince Kenyans that they had not achieved uhuru and were being taken for a ride by corrupt elite’s foreign backers, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga called upon under-privileged Kenyans to follow him towards a more just society.

When Odinga looked to see who was following him, it was not all under-privileged Kenyans regardless of ethnic group but fellow Luo regardless of social classes.”

In Nigeria, Mazrui observes, Awolowo, too, called upon his fellow countrymen to follow him towards a more just country. Just like Jaramogi, his rallying call attracted his fellow Yoruba regardless of their social class.

Mazrui’s observations rings a familiar bell in our minds when we critically analyse the trend of politics in Kenya – particularly as we gear up towards the 2022 General Election. One cannot fail to notice ethnic and or tribal alliances in Kenyan politics. Politicians often retreat into their ethnic strongholds to persuade the voters to register en masse.

Mazrui and Mazrui allude that Kiswahili language has only managed to ‘de-tribalise’ East Africans to some extent. This is certainly true in Tanzania and Kenya. The language enables members of different tribes to communicate with each other in various fora.

Most spoken language

What then should be the role and place of Kiswahili in Kenya’s politics? Kiswahili is the most spoken language in East Africa that cuts across all socio-economic, political and cultural milieus. Due to this fact, politicians should embrace it as they traverse the country to ask for votes.

In the 2013 General Election, the presidential debate shortchanged Kiswahili in that it was not given enough slots. The presidential aspirants should engage the electorate in a language that they can identify with and easily understand. In this case, Kiswahili should be the language rather than English. How do we expect ‘Wanjiku’, ‘Atieno’, ‘Nekesa’ and ‘Bosibori’ to understand complex issues on policies packaged in party manifestos in English – which they hardly know?

One may argue to the contrary that linguistic heterogeneity may not necessarily lead to national unity; just as linguistic homogeneity (as the case of Somalia) may not lead to the same. Due to the fact that Kiswahili is an official language alongside English, the elite politicians should make maximum use of the language to preach peace and harmony among Kenyans.

Enock Matundura, the translator of Barbara Kimenye’s Moses series (Oxford University Press), teaches Kiswahili literature at Chuka University. [email protected]