‘Mad Indian’ and unionist: Two forgotten First Liberation heroes

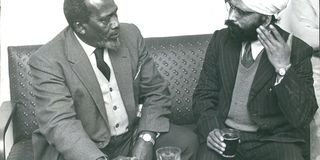

Makha Singh, author and veteran trade unionist, with former President Jomo Kenyatta. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Born in Kiambu in 1918, Kibacia attended the Kenya Independent School in Githunguri and later Alliance High School.

- In both the Mombasa strike and the riots in Nairobi, two men were marked and punished with long jailterms.

Makhan Singh, the veteran trade unionist and author, died last Thursday of heart failure in Nairobi.

On January 12, 1947, residents of Mombasa woke up to a ghost town. There wasn’t a shop open, no public transport, no schools open, and no activity at the usually busy Mombasa port.

The town’s workforce of about 15, 000 – largely consisting of Africans, Indians and Arabs — had gone on strike to demand better pay and working conditions for blacks.

The strike came as big surprise to the white colonialists, as they hadn’t imagined Africans had the organisational capacity to stage a massive strike and hold on for 12 days running.

It sent shockwaves all the way to the British parliament, as the Buckingham Palace demanded an explanation as to how “natives” had managed shut down His Majesty’s (King George V1’s) cherished territory in eastern Africa.

At the time Mombasa was the gateway to the colonies of Kenya, Uganda and Sudan. The colonial governor in Kenya was ordered to set up a tribunal to investigate the matter.

No uhuru, no Nairobi!

In March 1950, the Africans were at it again, when the King of England dispatched the Duke of Gloucester to Nairobi for the festivities to present Nairobi town with a charter proclaiming it as full-fledged city.

BOYCOTT CELEBRATIONS

When African leaders learnt about it, they hastily held a rally at Kaloleni in Eastlands Location and called upon Africans to boycott the celebrations. They reasoned that it wasn’t worth having a city when there was no freedom (uhuru) for the black people, who were the rightful owners of the land.

Come the day to present the charter, Africans not only kept away from all the planned festivities and refused to take all the freebies and enticements dished out by the colonialists, which included food and drinks.

The following week, Africans staged massive demonstrations to demand better working conditions and eventual independence. For a whole week, Eastlands was engulfed in smoke as Africans lit fires in the streets and colonial police responded with tear gas and live bullets. Thirty Africans were shot dead and many shops and other properties belonging to Africans razed.

UNSUNG HEROES

In both the Mombasa strike and the riots in Nairobi, two men were marked and punished with long jailterms. They were Chege Kibacia and Makhan Singh, a Kenyan of Indian extraction.

Born in Kiambu in 1918, Kibacia attended the Kenya Independent School in Githunguri and later Alliance High School. Some of his teachers were James Gichuru, Eliud Mathu and Joseph Otiende, whom he would later team up with to agitate for independence.

From school he had a stint as a journalist, working as an assistant editor in the African-owned newspaper, Sauti ya Mwafrika.

His heart was increasingly in fighting for the African labour force. He moved to Mombasa and got actively involved in trade unionism. With three-quarters of the African labour force earning less than Sh40 a month, a reasonable minimum wage was an immediate objective. A colour bar and limited opportunities for advancement were other causes for agitation.

Kibacia was also outspoken on the need to abolish the use of the kipande (identity cars) as a tool to discriminate against Africans. So much did he loathe the idea of carrying the kipande that even after independence and until his death in 1982, he refused to take a nation ID card! He believed his passport was enough, and mainly for travel outside the country.

ARRESTED

In the aftermath of the Mombasa strike and a series of others across the country, he was arrested, tried in a kangaroo court, and detained in Baringo district.

The matter of his detention was raised in the British parliament, where the colonial secretary state said: “Chege Kibacia is not exactly in detention, but has been removed from the area where he was misbehaving.”

In Baringo, Kibachia made acquaintance with local politician Daniel arap Moi and Moses Mudavadi, the father of Musalia Mudavadi, who was the area education officer.

Moi used to go to Kibacia and Mudavadi for evening tuition as he studied through correspondence at the British Tutorial College.

Though under preventive detention, Kibacia was allowed to roam a radius of five kilometres. Indeed, while still in detention, he managed to get himself a wife, Sokome Cheboiwo, who was working as a dresser at Kabarnet Hospital.

Moi remained a true friend and, a year after becoming president in 1978, he invited Kibacia and his family, who were living on State House Road, “for tea”.

When Kibacia was taken ill with stomach ulcers just before his death, President Moi paid all his hospital bills and when he died, police outriders escorted his casket for burial in Kiambu.

“MAD” INDIAN

While the white colonialists could understand Kibacia’s activism, they couldn’t comprehend what was “itching” Makhan Singh, a Kenyan Indian, to make him join the agitation for independence. They nicknamed him the Mad Indian.

Though the boycott and riots in Nairobi were led by African leaders, the colonial intelligence knew about be the hidden hand of Makhan Singh in the chaos.

He was arrested and charged with incitement and management of an “illegal” organisation.

At his trial, Makhan angered the white magistrate when he told the kangaroo court that the British had no business being in Kenya, and the sooner they granted independence to the Africans the better. At that juncture, the magistrate took on the role of the prosecutor to cross-examine him.

Magistrate: Are you sure Africans have the capacity to run Kenya left on their own?

Singh: Why not? It is their country so they would know how to go about it.

Magistrate: Where would they get judges, for instance?

Singh: From the people of this country.

Magistrate: There is no single African qualified in law!

Singh: The new government will give opportunities for training people to become judges, lawyers, magistrates, etc.

Magistrate: In the present state of the African, you would be content to appoint him a judge or magistrate?

Singh: Of course. If before the advent of the British they were able to judge about matters, even now they can do it.

The Mad Indian was jailed for 10 years.

Makhan Singh, the veteran trade unionist and author, died last Thursday of heart failure in Nairobi.

Born in December 1914, he received his early education both in India and Kenya, after which he joined the business of his father Sudh Singh, who owned Punjab Printing Press in Nairobi.

After his detention, he was released on the eve of Uhuru in 1961.

***

Any Kenyans of Chege Kibacia or Makhan Singh calibre still living today?

Several: How about Justice Mumbi Ngugi who, after years of business in corridors of justice, ruled that John Waluke and Grace Wakhungu had a case to answer for the theft of public money.

And what about Magistrate Elizabeth Juma who, after hearing the case, concluded that the two thieves pay back twice the amount they stole – a billion bob – or rot in jail? These are two Kenyans worth celebrating.