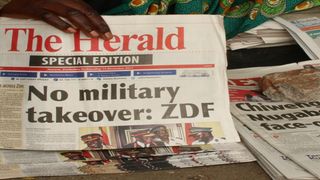

A vendor picks up a copy of the state-owned daily newspaper The Herald in Harare, Zimbabwe.

| Philimon Bulawayo | ReutersAfrica

Premium

In Zimbabwe, deteriorating press and political freedom

What you need to know:

- In recent years, there have been numerous reports of violence against journalists, fire-bombings of offices of media outlets and intrusion by security services.

- Colonial-era laws give the government a lot of power.

The Zimbabwe Constitution guarantees freedom of expression, but there is a dearth of laws that give effect to that and, since independence in 1980, there has been a general disregard of those liberties.

Instead of the promise of freedom, the state has focused on passing laws that entrench violations of freedom of expression. The 2013 Constitution, with its comprehensive and democratic Bill of Rights, was meant to rectify that situation, but freedom of expression in the media, or on the streets, is becoming increasingly difficult and dangerous.

The Mugabe regime was notorious for its brutality, oppression of hundreds of thousands of members of the southern Matabele tribal grouping, beating up protesters, detentions, fire-bombings and assaulting political figures like the attack on leader of the opposition, Morgan Tsvangirai. It was widely hoped that President Emerson Mnangagwa’s administration would do better – but it was also widely feared that it likely would not, since ‘the crocodile’ was the force behind much of the repression.

Systematic affronts

Since President Mnangagwa took over in November 2017, there have been systematic affronts on freedom of expression, with increasingly totalitarian response from the government to mounting criticism.

Reacting to assaults on their members, media freedom groups operating in the southern African region have come together to denounce the attacks.

The African Freedom of Expression Exchange (AFEX) joined with the Media Institute of Southern Africa, Zimbabwe Chapter (Misa Zimbabwe) to denounce violations perpetrated against Zimbabwe-based journalists.

AFEX said it had received reports of journalists being “abused by state and non-state actors in their line of duty”.

“In the most recent and worrying incident, unidentified armed men on August 21, 2019 at about 10pm raided the home of Samantha Kureya, a female comedian and political satirist working with the Bustop Television Station and assaulted her as well as some members of her family, including minors,” said the media organisation. “The unruly gunmen then abducted Kureya from her residence in Mufakose to an unknown location where she was severely beaten amidst reports of torture before being dumped,” it added.

According to media reports, Kureya — popularly known as Gonyeti — subsequently went into hiding. It was also reported that Kureya’s colleague, Sharon Chideu (Magi), “narrowly escaped abduction after she had been warned to move to safety”. Gunmen subsequently stormed her home to find she had fled. On August 23, 2019, “agents of Zimbabwe’s police arrested Leopold Munhende, a journalist working with online news portal, NewZimbabwe.Com”, while he was covering a demonstration by members of the Amalgamated Rural Teachers Union of Zimbabwe (ARTUZ).

Being a journalist will not spare you from beatings.

The journalist produced his accreditation card but this did not stop the officers from assaulting him as they took turns to beat him up with their batons. One of the officers is recorded shouting, “…being a journalist will not spare you from beatings”.

In recent years, there have been numerous reports of violence against journalists, fire-bombings of offices of media outlets and security service intrusion into their lives and work. Post-independence administrations inherited laws that were used by their white minority rule predecessors to consolidate power, such as the Law and Order Maintenance Act (Loma) and Official Secrets Act (OSA).

At independence, the ruling Zanu-PF (then Zanu) administration desired to create a one-party state and consolidate its power by limiting fundamental freedoms. The government established the Zimbabwe Mass Media Trust (ZMMT) in 1981 to administer post-independence print media reforms. This changed the ownership structure of the main daily newspapers in Harare and Bulawayo, The Herald and Chronicle, originally owned by a South African media entity, the Argus Company.

A man reads a copy of the state-controlled Herald newspaper in Harare, Zimbabwe.

The Mugabe government purchased the stock that the Argus Company owned and placed it under ZMMT with the state as the main shareholder. The Argus company was renamed the Zimbabwe Newspapers Limited (ZimPapers). The government later assumed full ownership of the ZMMT in 1996. The original intention of setting ZMMT was to “decolonise the media” and ostensibly not to control it. But full ownership of ZMMT gave close control of the media, including editorial policy, to the state.

With the emergence of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) in 1999 – Zimbabwe’s strongest opposition party since independence which threatened to end Zanu-PF’s stranglehold on power – there was a renewed focus on repression of free speech and of criticism in the media.

New sweeping laws – the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) and Broadcasting Services Act (BSA) – were enacted in the early 2000s and the Ministry of Information and Publicity given the responsibility of enforcing them.

In an effort to further close down democratic space in civil society, the Private Voluntary Organisations Act (PVOA) was enacted in 2002.

This law in particular was used by the state “with reckless abandon” to ban newspapers and silence dissent to the extent that most private and independent media houses resorted to self-censorship. This period also saw intensified brutality on dissenting voices, predominantly those who supported the pro-democracy movement.

Intimidation of journalists also escalated.

Inclusive government

Between 2009 and 2013, Zimbabwe had an inclusive government after the signing of the Global Political Agreement (GPA) that was mediated by South Africa. The agreement between Zanu-PF and the MDC acknowledged the role of the right to freedom of expression in a democracy. Media reforms were promised, including licensing of privately-run and community radio stations.

Two radio stations, Star FM and ZiFM, were licensed to operate and both started broadcasting in June and August 2012 respectively. However, this was a biased issuance of operating licenses at the expense of privately run commercial and community radio stations as both stations were state-aligned. Rather than promote media diversity, this facilitated concentration and a monopolisation of the airwaves. In 2014, the Ministry of Information, Media and Broadcasting Services initiated its Information and Media Panel of Inquiry (IMPI) to evaluate the Zimbabwean media industry and propose recommendations for reform.

But little has changed on the ground.

Among reasons are those old colonial-era laws that give much power to government, such as the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act, which makes it a crime to publish or communicate “false statements that are prejudicial to the state”, and attracting punishments up to 20 years’ imprisonment. Also included as crimes are “inciting or promoting public disorder or public violence or endangering public safety; or adversely affecting the defence or economic interests of Zimbabwe or undermining public confidence in a law enforcement agency, the Prison Service or the Defence Forces of Zimbabwe; or interfering with, disrupting or interrupting any essential service”.

Severe penalties

Another law expressly criminalises expressions that undermine the president. Due to these and other provisions, journalists, artists, and human rights activists are usually forced into self-censorship for fear of severe penalties. There are many cases of journalists being assaulted, intimidated and threatened while conducting their duties, which is a constitutionally guaranteed right.

Police officers and state security agents have been named as perpetrators in some cases. However, there is a “culture of impunity” and perpetrators are rarely put to account for violations. While a growing number of people are connecting to the internet as mobile phone technologies become more easily available, with a growing number using social media platforms to express their views.

Social media activism has intensified recently as tensions in Zimbabwe have mounted once again and have gone into overdrive during the Covid pandemic. Social media ‘mini-revolutions’ were part of the pressure that forced Mugabe to go in the end. But freedom of expression online is under threat as journalists and other media practitioners, including human rights activists, face repercussions for online criticism of the Mnangagwa government.

Responding to the threat, the Mugabe administration passed another law, the Computer Crimes and Cyber Crime Bill in 2016, which was revised and made tougher by Mnangagwa in a reiteration as the Cyber Crime, Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill (2019). Last year – as with 2016 when criticism of Mugabe and his regime were at their height – the authorities shut down the internet altogether. The Covid crisis has also demonstrated that a heavily polarised media environment has been fertile ground for the proliferation of false news spread through social media portals.

Anti-riot police carry a bag of baton sticks at Zimbabwe's constitutional and supreme courts in Harare.

The misgivings about the “mainstream media” have exacerbated the situation.

The state-controlled media is said to uncritically report on the government and ruling party activities while the private media is inclined towards the opposition and also self-censorship out of fear of harassment or arrest.

The information void created has been filled by social media with some “citizen journalists” also contributing to the spread of fake news with no fact-checking and quality control.

During the 2018 General Election, false news spread regarding the role of the army, polling stations, vote-buying and other poll-related matters proliferated. Also, during the anti-government protests in January 2019, protesters were subjected to police brutality and the government shut the internet. During that period, misinformation and disinformation escalated to the extent that it became difficult to even ascertain accurately the impact of police brutality and identification of victims.

According to Amnesty International, the Covid-19 crisis has become the pretext for a “surge in harassment of journalists and weakening of media houses” by states, including Zimbabwe. “Governments are targeting journalists and media houses that are critical of their handling of the pandemic,” Amnesty International warned on World Press Freedom Day.

“From Madagascar to Zambia (including Zimbabwe), we have seen governments criminalising journalists and shutting down media outlets that are perceived to be calling out poor government responses to Covid-19,” said the organisation.

Amnesty International

Deprose Muchena, Amnesty International's Director for East and Southern Africa, said: “With the disease continuing to spread, and no end yet in sight, there has never been a greater need for accurate news and information to help people stay informed and safe. Yet the authorities across the region are targeting journalists and media houses for their critical reporting on the pandemic which is weakening this vital information flow.”

Attacks had been recorded on the right to freedom of expression, media freedom and the victimisation of journalists for questioning government’s handling of the crisis. Journalists and newspaper vendors have been subjected to arrests and intimidation during their work in the context of the pandemic, said AI.

At least eight journalists had faced interference and harassment in the line of their duties. Two journalists were accused of working without accreditation cards, normally issued by the Zimbabwe Media Commission (ZMC), even though it is yet to issue the 2020 cards. Both journalists were reporting on the enforcement of the lockdown.

This harassment and intimidation of journalists prompted Misa, Zimbabwe Chapter, to eventually seek a High Court order that police and other law enforcement agencies charged with enforcing the Covid-19 lockdown “not to interfere in any unnecessary way” with the work of journalists.

Nevertheless, journalists remain acutely aware of the dangers they face.

For ordinary citizens, attempting to voice their concerns about anything by exercising their constitutional right to protest peacefully is to invite teargas, rubber bullets, beatings at the hands of police, arrest, imprisonment, or worse.