Purge in Jubilee mirrors plot against Tom Mboya in 1968

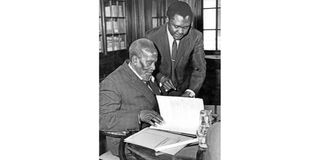

President Jomo Kenyatta (left) with Kanu secretary-general Tom Mboya after a three-hour National Executive Committee meeting at State House, Nairobi. The meeting was also attended by all provincial Kanu vice-presidents and vice-president Daniel arap Moi.

What you need to know:

- Mboya was well aware of the Sword of Damocles that this group hung over his head and expressed it in a candid interview with Stanley Meisler.

- Ronald Ngala was forced to give way for Daniel arap Moi as vice-chairman, in what was seen as punishment for his close association with Mboya.

- In May 1968, as delegates converged in Mombasa for a crucial conference, many believed Mboya would be ousted as secretary-general and replaced by Rubia.

The assassination of Cabinet minister Tom Mboya 51 years ago destroyed the touchstone of Kenyan politics. Despite him not holding a position of immense power, the politics of Kenya revolved around him. Politicians either sided with him or ganged up against him.

What made Mboya a force to be reckoned with was his enthusiastic personality and his trigger-quick mind, which always gave him qualities of natural leadership.

The “Gatundu Group”, which was made up of Kikuyu power barons nicknamed him “the rabbit” because of his smartness. They saw him as a threat to their grip on power and took every step to curtail his influence.

Mboya was well aware of the Sword of Damocles that this group hung over his head and expressed it in a candid interview with Stanley Meisler.

“I am aware of this. It is nothing new,” he said. “The problem is that there is no second man to Jomo Kenyatta, whom they see as a leader of the Kikuyu. I represent a threat to them.”

GIVE WAY

In what could mirror the current political happenings in Jubilee party, at the beginning of 1968 there were two major political developments whose target was to weaken Mboya.

First was the election of officials of the Kanu Parliamentary Group presided over by Mzee Kenyatta. All politicians allied to Mboya were purged from the committee and replaced by those favourable to the “Gatundu Group”.

Ronald Ngala was forced to give way for Daniel arap Moi as vice-chairman, in what was seen as punishment for his close association with Mboya. Other pro Mboya politicians who were purged from the group were William Malu, the MP for Kilungu, who was replaced as Kanu chief whip by Martin Shikuku, and Tom Malinda, the Assistant Minister for Agriculture, who was replaced as secretary by F Mati, the MP for Kitui North.

The parliamentary group meeting was followed five days later by the election of officials for the Nairobi Kanu branch. Nairobi being Mboya’s political base taking control of the city was key to Gatundu group’s ambitions.

Their candidate was Charles Rubia, a former mayor of Nairobi, who was making his debut in elective politics, while Mboya fronted Munyua Waiyaki. Before the elections, there were clashes between supporters of Mboya who wanted voting by secret ballot as stipulated in the Kanu constitution and those of the “Gatundu Group” who wanted voting by acclamation.

In the end, the “Gatundu group” had its way when their preferred way of voting was adopted. In the event, Rubia got 82 votes against Waiyaki's 73. This was strongly disputed by Mboya’s supporters who walked out in protest alleging that Rubia had only received 69 votes against Waiyaki’s 73.

REPEAT ELECTION

Consequently, Mboya’s supporters led by Clement Lubembe filed an appeal at Kanu headquarters demanding a repeat election claiming extra delegates were sneaked into the hall and that voting did not adhere to the party’s constitution.

Since Mwai Kibaki, who was the presiding officer had travelled abroad to attend the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development meeting, it was agreed that all parties involved should wait for his return for the matter to be resolved. Rubia was, therefore, prevented from occupying office until the matter was resolved amicably.

But backed by the “Gatundu Group”, Rubia wasted no time in waiting for the intervention. He headed to Gatundu where he was endorsed by Jomo Kenyatta as the duly-elected Nairobi Kanu branch chairman.

For the first time it seemed Mboya was losing his grip on Nairobi. Apart from the position of Kanu vice-president for Nairobi held by Mwai Kibaki, six out of the eight Nairobi branch office holders were now all Kikuyus supported by the “Gatundu Group”. On the other hand, Rubia's feet were now set firmly on the ladder with his eyes set for the position of Kanu national secretary-general held by Mboya.

GOVERNMENT MINISTER

The argument among the “Gatundu Group” was that the post of Kanu secretary-general should not be held by a government minister. In short, the stage was now being set for the next action which was the replacement of Mboya as secretary-general therefore breaking up his final grip on Kanu. They went as far as writing an unkind article targeted at Mboya alleging, "It is simply not possible as past experience has shown for any one person effectively to play this dual role."

In May 1968, as delegates converged in Mombasa for a crucial conference, many believed Mboya would be ousted as secretary-general and replaced by Rubia. But at the end of it all, he was back in Nairobi with his post intact having survived the night of long knives, a case of the proverbial cat with nine lives.

According to accounts given by those who were present at the meeting, Mboya had a bitter exchange with Attorney-General Charles Njonjo that most officials ended up siding with him. Mboya himself would later tell his American friend that those at the meeting felt Njonjo was taking his personal hatred for him too far.

For a time after the meeting, he felt the hostility towards him was subsiding. Mboya told his friend that he was now able to visit State House and meet Kenyatta, unlike before when he could only do so in the presence of Njonjo.

But this was only temporary for the “Gatundu Group” continued to connive against Mboya. The group also extended its spite and vindictiveness to Mboya’s American connections and sources of funds, which they were determined to cut off to destabilise him politically.

These connections were so much resented that when US vice-president Herbert H Humphrey decided to include American trade unionist Irving Brown in his delegation to Kenya in January 1968, US Ambassador to Kenya cabled Washington advising that Brown be dropped because of his closeness to Mboya.

However, after consulting American labour organisation, Humphrey ignored the diplomat’s advice, and travelled to Kenya with Brown.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Mboya’s project, the East African Institute of Social and Cultural Affairs (EAISCA), in particular became a major target for the “Gatundu Group” who thought it was being used by the Americans to channel money to him. The institute organised seminars on East Africa’s economic development and culture, and also set up a publishing house.

Controversy over the institute had first erupted in July 1967 in parliament when George Oduya, MP for Busia North, claiming to quote from a British newspaper, alleged that Mboya had received money from a CIA agent named Robert Gabor, a Hungarian-American who was also one of the sponsors of the EAISCA. These allegations were strongly denied by Mboya who said the article had been misquoted. This, however, did very little to calm his detractors.

On January 31, 1968, Mboya approached vice-president Moi and informed him about four EAISCA sponsors who were to arrive the following day. Among the sponsors were Gabor and another American called Richard Garver.

By informing Moi, who was also the Minister for Home Affairs, Mboya had sought to eliminate any suspicion about their presence especially after Gabor was mentioned in parliament. Moi assured Mboya that his visitors will arrive safely, and that he should not worry at all.

However, when the four landed in Kenya, Moi in connivance with the “Gatundu Group” declared them persona non grata and expelled them from the country without Mboya’s knowledge.

AMERICAN CONNECTIONS

The episode revealed how Mboya’s American connections, which had fuelled most of his achievements for Kenya, were now providing fodder for his opponents to spite and embarrass him.

The final onslaught against him was the introduction of constitutional amendments that raised the presidential age limit and removed the prerogative of electing a new president from parliament after it became apparent that he commanded great support among legislators.

Perhaps one thing they forgot was Mboya’s own organisational skills and influence within Kanu. He was one man who knew how to manipulate the Kanu constitution for his own political survival by making irresistible appeals to the delegates. Age was another great asset on his side. As he once said “The difference between them and me is that they are forced to run sprints to get to the top while I can afford to take it easy at the pace of a long distance runner.”

Mboya’s ambitions were cut short by an assassin on July 5, 1969.

The writer is a London-based journalist and researcher