End of an era as Kenyatta dies

What you need to know:

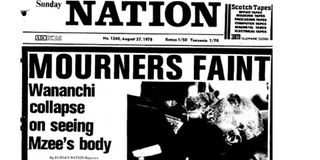

- As Kenyans filed past his coffin made of Africa oak with silver lining to the inside in State House, Nairobi, they fainted and wept.

August 22, 1978 was the darkest day in Kenya’s history.

The country was engulfed in grief following the death of Founding President Jomo Kenyatta.

It was the passing of an era and the beginning of another that came to be known as Nyayo era.

At exactly 3 pm, the following day Voice of Kenya veteran broadcasters Nobert Okare and Hassan Mazoa went on air in English and Kiswahili respectively.

After breaking the news, they announced repeatedly for subsequent hours between Marshall Music Mzee Kenyatta had died in his sleep while on a working holiday in Mombasa.

The government’s top machinery led by then Head of Public Service Geoffrey Kariithi had been working for a smooth transition of power to Vice-President Daniel arap Moi.

The announcement came as Mr Moi was being sworn into office by Chief Justice James Wicks at State House, Nairobi. For the next one week, the country was in mourning.

The world media and statesmen eulogized Kenyatta’s death as “the passing of an era” on the continent.

The Paris-based International Herald recalled Kenyatta had lived to prove that he was not “a leader to darkness and death” as the colonial government described him.

To the contrary, he was “a statesman of one of Africa’s stable and strongest economies, who Kenyans likened to (founding US President) George Washington.”

The Guardian was more poetic in its editorial pages. “The death of Jomo Kenyatta leaves the ranks of African politicians a gap the size of a colossus.

He gave Kenya tranquility in a turbulent continent. His name will be remembered along with that of Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Patrice Lumumba (Democratic Republic of Congo) and Abdel Nasser (Egypt).”

As Kenyans filed past his coffin made of Africa oak with silver lining to the inside in State House, Nairobi, they fainted and wept.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, his first Vice-President, with whom they had fallen out politically wept too after saying a prayer in Dholuo.

He put behind memories of his detention to tell the media he did not have differences with the fallen statesman.

“The only difference was on how things are done,” he said. Paul Ngei, his friend in the Kapenguria Six detainees described him as “father, liberator and a statesman.”

Upon his swearing in, Moi described Kenyatta as “my father, my teacher and my mentor.”

It was on August 31, 1978 that world leaders and delegations converged on Nairobi for the final farewell to one of Africa’s revered statesmen.

The Daily Nation in a front page story headlined FAREWELL penned: “Kenyans yesterday bid farewell to the Father and Founder of their Nation in the most impressive ceremony ever seen in Black Africa.”

The coffin draped in Kenyan flag was carried on a two-tonne horse drone carriage from State House to Parliament Square before heads of state and representatives from 85 countries.

Police estimated 500,000 people filled roads and perched on trees and buildings to witness the burial.

Although Moi’s swearing in was smooth, the build up had been eventful with some politicians allied to Kenyatta trying to change the Constitution to bar him.