Mental health crusade born of bike accident

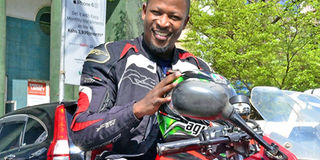

Bill Kasanda, a biker and digital marketer, poses for a photo on his bike outside Nation Centre on September 21, 2019. PHOTO| FRANCIS NDERITU

What you need to know:

- “My first reaction when the doctors told me they would have to amputate my foot, was: what would happen to the things I had been planning.

- My girlfriend’s birthday was supposed to be in two weeks and I was planning a surprise for her. I broke down, telling her what I was thinking, and she looked at me as if I was crazy because that should have been the least of my worries,” the biker adds.

It is Sunday at around 5pm in October, 2015. Three friends — Geoffrey Gitaka (GG), Bill Kasanda and Paul Gachemi — have made it to the finals of the National Motorcycle Racing Competition to be held on Kiganjo Road in the heart of Kiambu County. However, this particular race is different — 26-year old Kasanda, a rookie, is competing against veteran motorcyclists and the crowd is eager to see how he will perform.

The competitors have to race up the S-curved road and back. The first one back will take home the title. Braking last on the sharp curves means you automatically pass the rest. Going at over 200km/hr, the trio race past the first curve.

Paul brakes first, GG second and Kasanda last. This gives the newbie an advantage as he overtakes GG, putting him in second position.

The disadvantage, however, is that he has carried too much speed into the first corner. On reaching the second, he loses control of the bike and releases it from his grip.

What follows next is a scene that might as well be from a movie. Kasanda’s bike crashes into a road sign, and he is violently pushed to where the bike crashed and thrown back onto the road.

GG, now in third position cannot see that his friend is lying on the road because of the dust all over the scene of the accident. Miraculously, GG avoids him and races forward.

When the commotion stops, Kasanda sits up to figure out how to get back on his bike in his quest to win.

To his shock, he sees a pool of blood rushing out of his legs, the right one however is worse off. His adrenaline at a rocket high means he is not in any pain. Medics reach the scene and deliver a blow — he has lost his foot and needs to be rushed to hospital.

Fast-forward to 2019.

HAS COME A LONG WAY

Four years after the accident, Kasanda has come a long way. He is an adaptive athlete, digital marketer and amputee and, most interestingly, he still rides his motorbike, thanks to a prosthesis, and competes to date.

“At some point, when things were going down the drain and I was hitting rock bottom, I hated my bike, the racing, and I thought that the whole sport should just be banned. However, I realised that it was not the bike; the bike had no bad intentions towards me. That pushed me to get back on it and still race,” he says.

Getting to this point has, however, come with its own challenges. When he reached the hospital, a team of doctors told him that due to the way his right foot was detached, they could not reattach it, therefore it had to be amputated.

“My first reaction when the doctors told me they would have to amputate my foot, was: what would happen to the things I had been planning.

My girlfriend’s birthday was supposed to be in two weeks and I was planning a surprise for her. I broke down, telling her what I was thinking, and she looked at me as if I was crazy because that should have been the least of my worries,” the biker adds.

Each bike was equipped with a camera. In this case, GG’s camera should have been able to capture exactly what caused Kasanda to lose his foot. Unfortunately, there were many races that day and the camera’s battery lost power.

“I would want to see what happened, just out of curiosity, and to understand what it looked like. I love watching thriller movies, so this would be so thrilling,” Kasanda says between laughs.

His bright, exuberant nature towards life would lead some to think that the recovery was a breeze for him. However, for a young man with a career ahead of him, he found himself in a painful and confusing period.

“I am one person who is okay with some level of pain, but that pain was too much. I could not even push my wheelchair. The doctors gave me strong painkillers, of which I was taking one dose. But one day I took a double dose, which left me asleep for 16 hours. My family and friends thought I was dead because I kept drifting in and out of sleep.”

The mental weight was equally, if not more, intense.

“I come from a traditional family and I knew that as a man, there are certain things expected of me and mental health was not among them. After the accident, I sank into depression and I had no idea what was happening to me. I was also paying my brother’s fees at the time and I knew the fees would not care that I had been in an accident. Luckily, my brother’s teacher understood and we worked something out.”

Through a fierce battle within himself, the fifth born in a family of eight managed to dig himself out of that dark place through therapy.

“My outlet during the depression was food and anger. I gained too much weight. From 78kg, I ballooned to 115kg on a wheelchair. I also started gambling. My emotions were so displaced that I let out my anger on my close ones, instead of dealing with them head on. When I started therapy, it changed a lot. It taught me it’s okay not to be okay.”

Depression is often thought of as a silent killer, but its impact can lead to more detrimental effects, especially among men. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), out of 421 cases of suicide reported in 2017, 330 were men.

His experience sparked a passion for mental health, which has seen him work tirelessly to raise awareness on the condition.

Through his campaign, “One leg at a time,” he has so far climbed Mt Longonot using crutches. He is also striving to tour all the 47 counties to raise awareness on mental health and train teachers and supporting staff on the issue.

“The other day a young girl took her life which should never have happened. It would be great if one day we have mental health being factored in our curriculum, but until then, we must continue to push the conversation about it, no matter how uncomfortable that may be.”

The resilient digital marketer is relentless in seeing that mental health is treated with the seriousness it deserves, especially in one of the biggest mental health facilities in the country that is often perceived in a bad light.

“There has been a huge stigma surrounded around Mathare mental facility and for some people, their worst fear would be to end up there. I want to change that narrative and sleep in Mathare for three days, and come out of there to tell people what I experienced. If people could change the mentality they have about Mathare, then I hope they will be okay with seeking medical health.”

With his thirtieth birthday coming around the corner, what would he say if he was sitting across from the Bill Kasanda from four years ago?

“If I were to tell the Bill Kasanda from all those years ago anything it would be, to be okay being vulnerable as a man. Not to be defined by the possessions that he has, the biking, or what society tells him to be. I would tell him to redefine himself as a man and prepare himself for the ‘what if’.”