Ngugi’s new book will only embolden African dictators

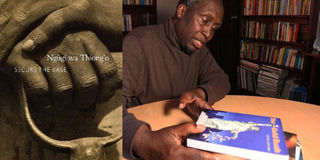

Renown literature scholar Ngugi wa Thiong'o in Nairobi on June 2, 2015. PHOTO | BILLY MUTAI

What you need to know:

- The foremost Kenyan writer remains optimistic though. Despite the many problems facing Africa, Ngugi doesn’t forget to commend us for the far we have come.

- Unlike in his fiction, where Ngugi urges us towards a utopia in which we have worked to solve our most intractable problems, in the essays the author doesn’t go far beyond pointing out our problems and their colonial origins.

- Ngugi seems now to be enamoured of what Johan Galling has elsewhere called “negative peace”, a situation in which the nation is not at war but its citizens continue suffering at the hands of elites.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s new collection of essays is provocative partly because of its contradictions. Titled Secure the Base, the book is concerned with Africa’s visibility in the globe.

Throughout, Ngugi laments the continued exploitation of the continent and the persistent “dark continent” image in the western media and scholarship. Nobody can argue against him on that.

The foremost Kenyan writer remains optimistic though. Despite the many problems facing Africa, Ngugi doesn’t forget to commend us for the far we have come. “Any discussion of the continent must take into account the depths from which Africa has emerged and the world forces — from slavery and colonialism to debt bondage— against which it has had to struggle.”

Unlike most scholars of Africa today, Ngugi does not confine himself to a small region of the continent or a few privileged texts; rather, he draws from his native Kenya, and uses examples from across the continent. Ngugi writes with his signature humility, deceiving simplicity, ethical commitment, and accessibility.

The result is a book that celebrates the diversity of the continent while revealing our shared vulnerabilities across national and linguistic boundaries. The most stimulating parts are when he offers anecdotes about his experiences in colonial and post-colonial Kenya to suggest that there have been no substantive changes since the 1950s.

THORNY ISSUES

It’s hard not to admire Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the Kilimanjaro of African literary majesty. I was recently accused by a Kenyan writing for a Nigerian blog of promoting Ngugi’s work on tribal grounds. Why can’t that blogger come here and debate me?

That said, we should read Ngugi objectively and highlight his strengths (which are numerous) while pinpointing his few weaknesses, regardless of our ethnicity or ideological orientation.

Ironically, when my dog Sigmund and I got our low-paying job in an American university, two professors at the University of Nairobi literally put their heads together to develop a “hypothesis” that I was hired by the CIA to bring Ngugi and other African Marxists a peg or two down. Who am I?

I have had no incentive to debunk that “hypothesis” because it keeps petty muggers away from me in Nairobi streets, for they fear that I’m guarded by invisible lethal fellow spooks.

In the new book, Ngugi covers a wide range of thorny issues, including the 2007/2008 post-election violence; the privatization of resources in Africa and the role of intellectuals in local knowledge production in indigenous languages.

Unlike in his fiction, where Ngugi urges us towards a utopia in which we have worked to solve our most intractable problems, in the essays the author doesn’t go far beyond pointing out our problems and their colonial origins. By tying African predicaments to a past we can do very little about today, the optimistic book rebels against its hopeful author and ultimately becomes the most pessimistic work I’ve ever read.

To young scholars, Ngugi might even sound little a bit out of date. For how long shall we continue blaming colonialists for problems we have created for ourselves? For example, can the British be really to blame for the assassinations we are witnessing in Nairobi today, the flooding in our city streets, or for a population that votes thieves and fools to office or worships comical demagogues as national opposition leaders?

In the 1980s, Chinua Achebe argued in The Trouble with Nigeria that our problems mainly stem from poor leadership. Old Albert Chinualumogu might have been right then.

Most leaders at that time had imposed themselves on the people either through military coups or by rigging themselves back to power in sham elections.

The greatest tragedy today is that the most despicable dictators in Africa would win the polls without stealing a single vote. They only rig elections and harass the opposition probably just because it is in their DNA to be nasty people.

I usually tell my good friends and mentors Robert Mugabe, Paul Kagame, Brother-in-Christ Pierre Nkurunziza, and Yoweri Museveni not to rig elections any more. Africans have now accepted their dictators and tribal tin gods as their saviours against foreign meddling.

Once a dictator secures an ethnic base by rallying the people against some colonialists as Ngugi does in his book, the dictator can proceed to preside over corruption; order assassinations; assassinate the assassins and any witnesses. Do we, then, still blame colonialists for this as Ngugi seems to be doing? Really?

NEGATIVE PEACE

It might be more strategic (pace Ngugi) to connect our problems to the current political order and our self-colonising habits than blame colonialists. This way we would be able to come up with practical ways of changing our situation, especially changing our pathologically tribal mindsets.

We cannot stop the realities of globalisation, but at least we can kick out of office corrupt leaders who hide stolen money in global offshore bank accounts.

I sometimes suspect that African intellectuals like railing against abstractions like colonialism and globalisation in order to avoid criticising their corrupt tribe-mates currently in power.

Ngugi seems now to be enamoured of what Johan Galling has elsewhere called “negative peace”, a situation in which the nation is not at war but its citizens continue suffering at the hands of elites.

Where is the revolutionary Ngugi who would teach us how to chase the rich from our beloved country to, say, Kisimayu to live with their fellow terrorists, as there’s no difference between our political elites and terror gangs? I think, if we managed to chase them out of Kenya someday, our so-called national leaders and their partner thieves in the corporate world would serve as good wives of al Shabaab.

Lastly, as my dog Sigmund will tell you when he’s in a happy mood and not doing his fishy CIA assignments, since reading Ngugi’s Decolonising the Mind immediately it came out in 1986, I’ve been a committed supporter of African writing in African languages.

Ngugi’s great new book should have been written in Gikuyu.